Washington (AFP) - When a person suffers an opioid overdose, their respiration is "slowed to the point that you're not breathing," social worker Johnny Bailey explains, speaking to a rapt audience at a nonprofit office in Washington earlier this month.

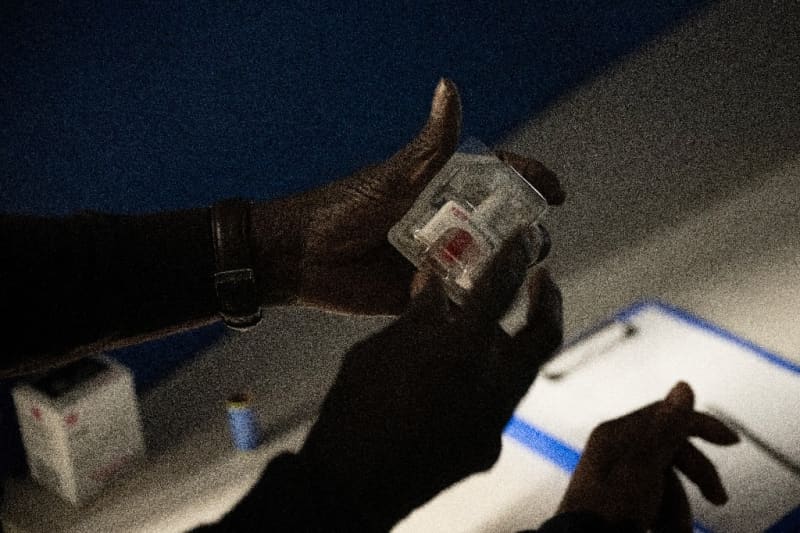

Bailey is training attendees in the use of Narcan, a drug that reverses overdoses caused by opioids such as fentanyl, a narcotic 50 times more powerful than heroin.

Narcan will "bring someone back from basically the dead," the 47-year-old recovered drug addict said at the offices of HIPS, an organization that provides "harm reduction" services to sex workers and drug users.

The drug's nasal spray form, which has been authorized in the United States since 2015, has become an indispensable tool in the fight against the opioid epidemic gripping the country.

The goal of organizations such as HIPS is to make Narcan readily available to the public, similar to installing fire extinguishers to fight fires or defibrillators to restore a heartbeat.

A group of around 10 people are attending the presentation by Bailey at the HIPS headquarters in early March.

The first lesson: determining whether someone is indeed suffering from an overdose.

"The things you want to worry about are grey, purple or blue lips or nails, difficulty breathing," Bailey said. "But most importantly, someone who won't wake up."

The next step is to call emergency services and administer Narcan immediately by inserting the nozzle into the person's nostril and pressing the plunger to deliver a dose.

If they do not regain consciousness within two or three minutes, another dose can be administered in the other nostril.

The overdose victim should then be rolled over on their side into the "recovery position" to prevent them from suffocating in the event they vomit.

Narcan works quickly by sending molecules called naloxone to the brain, where they displace opioid molecules on receptor sites to reverse an overdose.

Giving it to someone who has not experienced an overdose is not harmful.

'Common'

Among those attending the training session was Awa Sargent, 27, who lost a friend a month earlier to an opioid overdose.

Another participant was Starr Miller, 40, who came across an overdose victim while out shopping.

"I was on my way to get groceries and someone was laid out, not breathing, at the bus stop," Miller said. "Unfortunately, that is a common thing to see.

"If myself or someone else had Narcan we definitely could have helped that person sooner," she said.

Miller said emergency responders "did arrive pretty quickly" and were able to revive the overdose victim.

Nearly 450 people died from overdoses in the nation's capital in 2022, more than twice the number of homicides recorded last year.

Nearly all of the deaths were related to fentanyl, which is sometimes added to cocaine or other illegal drugs.

The opioid epidemic is growing in the United States -- between 2020 and 2021, the number of deaths linked to opioid overdoses jumped 17 percent, from 69,000 to 81,000.

The authorities in Washington have been aggressively promoting Narcan with giant billboards and a "LiveLongDC" text number that will show where it is available.

Metro train employees have recently been supplied with Narcan and groups distribute it on the street -- more than 17,000 doses last year from HIPS alone.

"We've trained so many people who have ended up saving lives," said Bailey -- library employees, nightclub workers, members of religious congregations and others.

"I can tell you how to use Narcan in two to three minutes," he said, but the one-hour training course "makes people understand more about the issue."

'Good Samaritan'

Bailey explains to the course participants that a so-called "good Samaritan" law will protect them from any legal fallout from administering Narcan.

Narcan can already be obtained in pharmacies in certain states without a prescription, but the US Food and Drug Administration wants to extend the practice nationwide and also make it available over the counter in supermarkets and convenience stores.

"We need to destigmatize and normalize the use of naloxone," said Scott Hadland, chief of the Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital.

"Putting a prescriber between a person and their access to naloxone creates an unnecessary barrier," Hadland said.

Leslie Walker-Harding, a pediatric doctor in Washington state, played down concerns that drug use could increase if people knew there were a ready antidote.

Walker-Harding compared it to the launch of the "morning after" contraceptive pill.

"People worried kids would have more sex," she said. "You know, that's just not how people think. And it's not how people who have an opioid use disorder would think."

Allowing Narcan to be sold without a prescription would allow it to be dispensed through vending machines at any time of the day or night.

HIPS is preparing to put three such machines into service.