The Linear (L0) “Maglev” motorcar on the test track in Yamanashi Prefecture. CC License, Wikipedia, Saruno Hirobano

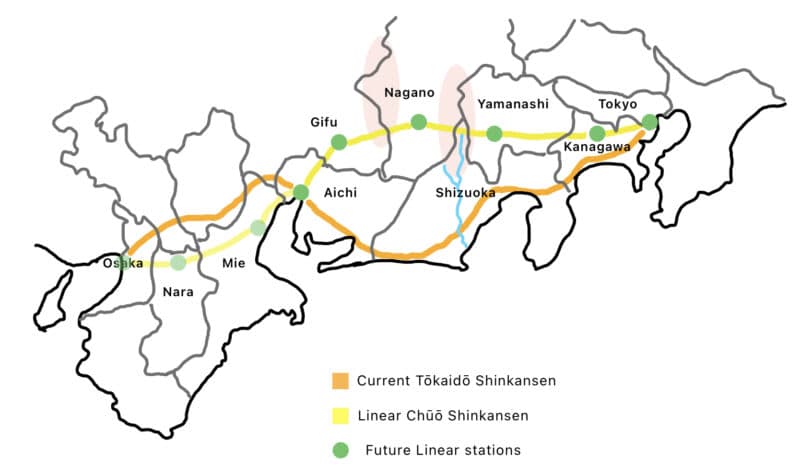

For decades, Japanese business and government leaders, as well as much of the media, have hyped the country’s planned bullet train, the Linear Chūō Shinkansen (Linear). The magnetically levitated (“maglev”) bullet train can reach speeds of 500 kilometers per hour and is scheduled to link Tokyo to Nagoya in 40 minutes by 2027 and to Osaka in just 67 minutes by 2045.

That would hypothetically beat the current bullet train, the Tōkaidō Shinkansen, already running between those cities by about 50 minutes and an hour and a half, respectively.

The private company behind the project, JR Central, claims that the Linear will bring huge economic benefits by bolstering Japanese industry — particularly if the maglev technology gets exported abroad.

However, since construction began in 2014, many Japanese residents have only seen its rising costs with few of the anticipated advantages.

For starters, Japanese taxpayers are being asked to foot a large part of the staggering JPY 9 trillion (USD 60.7 billion) in projected costs. In 2016, for example, the administration of then Prime Minister Abe Shinzō lent JR Central an astounding JPY 3 trillion (USD 20 billion) of ultra-low-interest, long-term loans from state funds.

On top of this, local prefectural governments and taxpayers are shouldering the bills for constructing new train stations for the Linear. By JR Central’s own estimates, the average cost for station buildings alone is JPY 35 billion yen (USD 236 million), even reaching JPY 220 billion (USD 1.4 billion) in the case of Kanagawa Prefecture.

This seems like a steep price to pay especially when considering that JR Central’s own president admitted that the maglev won’t turn a profit domestically but will rather mainly be used to sell Japanese technology abroad.

In addition to taxpayers’ wallets, the Linear is taking a toll on the natural environment as well.

For instance, while its supporters highlight the train’s “clean” and CO2-saving credentials, the Linear will, in fact, use anywhere from three to four times as much energy per person to power as the current Tōkaidō Shinkansen. Most of this energy will be sourced from fossil fuels and nuclear.

Moreover, a staggering 90 percent of the Linear's journey from Tokyo to Osaka will be entirely underground, including 70 kilometers that pass directly underneath the pristine wilderness of the Japanese Alps.

A map of the Linear Chūō Shinkansen (“maglev”) route overlaid with the current, Tōkaidō Shinkansen. The Japanese Central and Southern Alps are in light pink. The Ōi River, in Shizuoka Prefecture, is light blue. Author’s rendition, based on plans from JR Central © Justin Aukema

This is already producing massive amounts of soil and dirt waste, some of which is contaminated with toxic chemicals such as arsenic and mercury, and almost all of which have no decided use or storage location. It is estimated that tunnel construction between Tokyo and Nagoya alone will produce 56.8 million cubic meters of dirt.

Since only a fraction of this can be reused, most is instead being used to fill in gorges and river valleys. But this has many experts and residents living downstream fearful about possible landslides caused by heavy rains.

Others are worried about the impact of the tunnels on surrounding communities’ water supplies, especially since many major streams and rivers originate under the Japan Alps. Indeed, JR’s own survey found that its tunnels would cause two metric tons less water to flow into the Ōi River every second. This has so worried the residents of Shizuoka Prefecture, who rely on the river for their livelihoods, that Governor Kawakatsu Heita has withheld his approval for maglev construction through the prefecture.

The Linear “brings absolutely no benefit to the prefecture,” Kawakatsu stated.

Shizuoka resident Tsuji Hiroshi, 86, agreed. In an interview with the Asahi Shinbun, he recalled when another train tunnel in the 1930s destroyed underground aquifers and local farms. “Once the water's gone, it never comes back,” he lamented.

Yet perhaps the greatest cost of the Linear project has been the human one.

On the night of October 28th, 2021, for example, tunnel worker Kosaka Kōki (44) was crushed to death by falling rocks while inspecting the results of a dynamite blast on a section of the Linear tunnels in Gifu Prefecture.

At least four other major workplace injuries have occurred in Nagano Prefecture alone during the maglev construction.

And construction workers aren’t the only ones feeling the pain. Many residents, including 100 homes in Sagamihara, Kanagawa Prefecture, are being forcefully relocated to make way for the incoming train.

Sagamihara City is kicking residents out over a 13.7-hectare area to build a new Linear station to the tune of JPY 53.8 billion (USD 363 million), 33 billion of which is coming from public funds.

Although the affected residents are reimbursed, lands are seized under laws similar to eminent domain, and many are unhappy with the negotiation results.

In 2022, the city surveyed 373 residents about their thoughts on the new station development, with 316 of those — an overwhelming 85 percent — responding that they were outright opposed to it. “We don’t need the Linear,” said elderly resident Akeishi Kazuko, whose house is one of those in the proposed demolition path, according to the survey report.

Local popular opposition has been so great that between 2016 and 2023, 780 Tokyo and Kanagawa residents filed a class action lawsuit against the Japanese government for approving the Linear project without fully assessing its true costs.

A similar story has unfolded in Ida City, Nagano Prefecture, where 190 households are being forcefully relocated to make way for a new Linear station there.

One affected resident, Kubo Miki, told the local news outlet Shinano Mainichi Shinbun that she feels she “doesn’t have a voice.” “I’m really upset,” said another, “it was a really quiet, peaceful place, and I thought I’d live out my last days there.”

Others, including one elderly woman, have simply given up trying to push back. “It’s useless to protest since it’s a national policy,” she said.

Residents of Nagano’s Ōshika Village, a sleepy hamlet in the Southern Alps, are also unhappy. As a 2020 documentary explained, tunnel construction for the Linear there, where up to 1,763 dump trucks barrel down the narrow mountain roads per day, has already “wreaked irreversible damage on the natural ecosystem and for local residents.”

Lamenting the destruction of the village and its surroundings, local dairy farmer Kobayashi Sunao said, “Once the natural environment has been destroyed, it’s gone forever.”

Indeed, JR Central’s plan to drill through the Japanese Alps has not been popular, especially with locals. A 2011 government survey, for instance, found that 648 of 888 respondents, or 73 percent, said they were opposed to the Alps route and that the plans should be scrapped.

Still, much of this popular opposition seems to be falling on deaf ears.

Meanwhile, at the end of the track, in Japan’s Kansai region and the city of Osaka, where JR Central hopes to extend the Linear by 2045, many people still aren’t aware of its true costs.

Local businesses and politicians there have been eagerly promoting the new maglev. Nara City, for example, released a promotional video for the train featuring pop idol Ōnishi Momoka and has plastered JR Nara Station with pro-Linear advertisements.

A staircase heading to JR Nara Station is painted with a pro-Linear ad that reads “Bring the Linear to Nara.” Photo by the author. 4 January 2024.

The Osaka government has also voiced its strong support for the Linear.

There are some exceptions, however. Retired school teacher Kasuga Naoki and a small group of others started the Linear Citizen’s Network Osaka in 2015 to raise awareness about the maglev’s problems.

The group petitioned the Osaka government, calling for it to withdraw its support for the Linear, citing safety and cost concerns.

But they’ve struggled to get their message to a wider audience.

“The local government and some big businesses are pushing to get the Linear built,” he explained to Global Voices in a recent interview. “These pro-Linear groups just emphasize how great the Linear is,” but tend to ignore its negative aspects.

As a result, “many people in Osaka[…] aren't aware of the Linear’s problems,” he continued.

Still, the Linear project continues to move forward. Now, many like Kasuga worry that people won’t feel its true costs until it’s already too late.

Written by Justin Aukema

This post originally appeared on Global Voices.