Graffiti paintings on the Israeli West Bank barrier by Banksy near Qalandia – July 2005. Photo by Szater on Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Note: This post contains graphic imagery in the links, which may be disturbing to some readers.

During my childhood living in Jerusalem and the West Bank, I absorbed the lessons taught in elementary school that painted a picture of justice prevailing in the universe.

However, my experiences at the Qalandia checkpoint, where Israeli soldiers treated Palestinian children and adults going to school and work with hostility, made me question these teachings. We are humiliated every time we go through the checkpoints. We are forced to stand in line for hours every morning while our bags are searched and our birth certificates (koshan) and IDs are examined.

In the 2004 documentary by the MachsomWatch (Checkpoints Watch), a group of Israeli women who monitor and document the conduct of soldiers and policemen at checkpoints in the West Bank, I'm standing on the right side next to my father at minute 9:11. I was only six years old at the time, attending first grade. We were yelling at the soldier to let us pass because we were late for school and had exams. I remember my father being very frustrated then.

Despite these experiences, our Palestinian curriculum led us to believe in the existence of an efficient sophisticated council (the United Nations) where nations came together to address global issues and prevent wars and atrocities.

I witnessed the Israeli construction of a 9-meter (30-ft) high concrete wall, which began in the year 2002 and was later identified as “the apartheid wall.” The wall separated my school in Beit Hanina from my home in Kufarakab and created a barrier between my house and my cousins’ house. The wall sparked my curiosity about the term “apartheid.”

I remember hearing the sounds of construction of the apartheid wall down the street from our school, at the same time I was learning about the “Nakba” and all the pain associated with the word.

The Nakba, an Arabic term meaning “catastrophe,” refers to the events surrounding the 1948 Palestine war, which gave way to the establishment of the state of Israel. There were several massacres perpetrated against Palestinian civilians by Zionist paramilitary groups, which later became the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF), or what many refer to as the Israeli Occupation Force (IOF)%20Continue%20Systematic%20Attacks%20against%20Palestinian%20Civilians,the%20Occupied%20Palestinian%20Territory%20(OPT)).

Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were forced to flee or were expelled from their lands, leading to significant refugee populations in neighboring Arab countries and beyond. Generations have lived stateless in refugee camps in Lebanon, Jordan and Syria, still waiting to return home 75 years later.

As little children in school in Jerusalem, we were convinced the answer was as simple as one plus one equals two; surely, the world allowed the Nakba to happen because they didn't know it was happening. According to the morals we learnt in our classroom as children, human lives matter regardless of religion, background, and language.

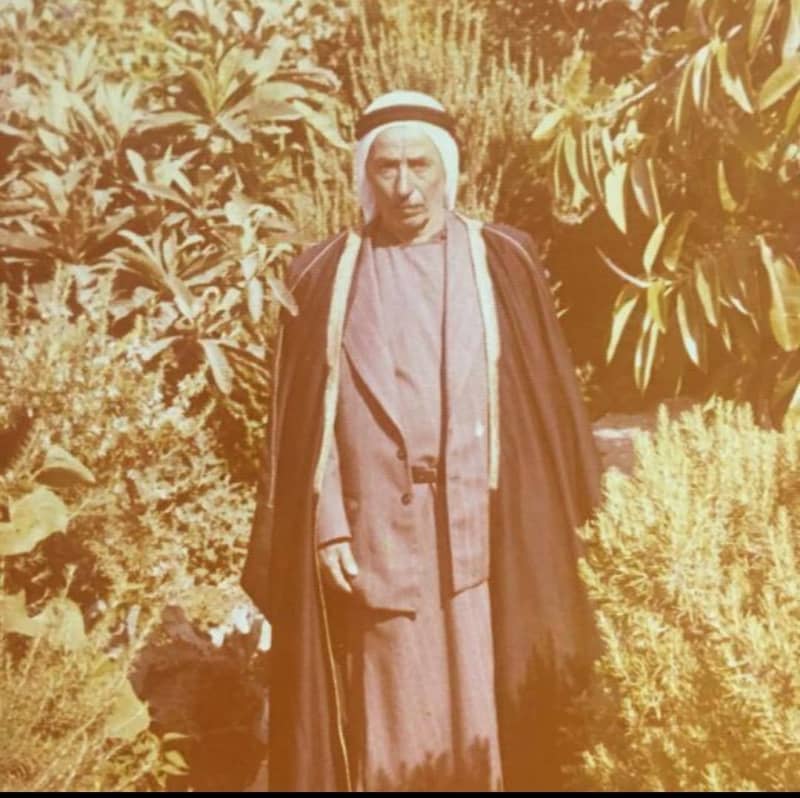

The author's great-grandfather, Hamed Zughaiar, standing in the backyard of his own home in Kufarakab, West Bank, Palestine. Photo taken by his grandchild, Hamed Zughaiar Junior, in 1977, used with permission.

Our grandparents and great-grandparents who experienced the Nakba were blindsided by the terrorist Israeli mobs. My great-grandfather Hamed Zughaiar lived in Jerusalem’s old city in the same house as a Palestinian Jewish man called Mordachay in the 1920s. My Muslim great-grandfather spoke Yiddish, and his neighbour and friend Mordachay spoke Arabic. Hamed and Mordachay both worked as shoemakers in what is currently called Machne Yehuda market long before the establishment of Israel. My great-grandfather trusted the Jewish population, as he saw them as equals. The Nakba left deep generational traumas on my family, stories of which we still recount to this day. In 1946, my grandfather bought his dream house near the Jerusalem Cinematheque, only to be forced to flee with my great-grandmother Nazeemeh two years later. Upon their return a few days later, they found that the house had been occupied by an Iraqi Jewish family. Just like that, his dream house was gone. The only explanation that made sense to me is that they didn’t have phones back then, so they couldn’t videotape the atrocities they experienced; therefore, no one could save them.

The Gaza Nakba of 2024

It has been a prolonged period marked by the harshness of winter, typically a season of joy and life in Gaza, but now made severe by the cruelty of displacement.

The days are coloured by the stark hues of starvation and death. Among shattered tents and fragmented hopes, homes lie in ruins, with demolished souls, orphaned children, and buried family members in the rubble of the houses they were told were safe by a cruel regime that seeks to erase them.

The horrifying scenes include unclaimed decomposed bodies on pavements, mass graves, martyrs without graves, and human remains hanging from trees and windows from the impact of explosions. Those who survive the daily barrage of bombs are left sleeping on the cold ground under makeshift tents made of plastic wrap. The atrocities unfold in a relentless cycle, casting a long and ominous shadow over the conscience of the world.

A Palestinian girl and her mother emerge from under the rubble in Khan Yunis, south of Gaza City, November 7, 2023. Photo by Mohammed Zaanoun @m.z.gaza on Instagram, used with permission.

Children have matured in those 150 days, tasked with vlogging the war and documenting the unfathomable horrors around them. They witness their loved ones dying of starvation and bid farewell to their younger siblings and playmates. In this dystopian reality, we see a father bearing the heart-wrenching burden of carrying the remains of his children in plastic bags, making an agonizing plea for the world to bear witness. A world that knows exactly what's happening, as the atrocities are broadcasted on social media. Yet, it has become deaf, mute, and complicit.

We are witnessing the gradual dimming of the spark in the eyes of innocent children, the vloggers growing thinner, and journalists becoming the news; Wael Al Dahdouh, a prominent Palestinian journalist who has been on our TVs since 2004, bid a final farewell to his wife, son, daughter, and grandson. They were killed in an Israeli air strike that hit their house on October 25 while Wael was reporting the news. Two and a half months later, his son Hamza Al Dahdouh was killed by an Israeli airstrike while driving a clearly marked press car.

So far, 126 journalists have been killed by Israel in Gaza in an obvious attempt to silence Palestinian voices showing the world the daily war crimes.

Reflections on injustice

I apologize that all we can do is watch helplessly as our people decay on our screens, dying for 150 days a few kilometres away from us in the West Bank and Jerusalem. It is unjust that the world deems Gazans as terrorists and collateral damage, with over 30,000 killed, because Israel claims the right to defend itself from those it occupies and oppresses.

I lament that we live in a world where funds can swiftly be cut from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) based on mere allegations by Israeli officials.

Meanwhile, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) takes its time to decide whether the deliberate killing of over 30,000 people, along with the acts of starvation, bombing, shooting, and torture endured by others over 150 days, qualifies as genocide. This delay in justice starkly reminds us of the persisting injustice that persists.

Perhaps we should turn to the very schoolchildren taught about justice and ask them if what the world refuses to see is considered genocide.

Written by Asia Zughaiar

This post originally appeared on Global Voices.