By Hans Nicholas Jong

JAKARTA — The Norwegian state pension fund has cut ties with U.K. conglomerate Jardine Matheson (Jardines) due to concerns that the group’s gold mining activity in Indonesia could damage the only known habitat of the most threatened great ape in the world, the Tapanuli orangutan.

Environmentalists have welcomed the decision, saying that it should serve as a wake-up call for Jardines to not expand the mine into the orangutan habitat and for other investors to stop financing companies that threaten the environment.

On Feb. 29, the fund, the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world, with $1.6 trillion in assets, announced the decision to sell out of its investments in Jardines and two related companies, Jardine Cycle & Carriage Ltd. and PT Astra International Tbk.

The Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global was among the largest external investors in the conglomerate, with $236 million worth of shares in the three companies at the end of 2022.

The Norwegian fund joined the list of 29 financiers that have excluded Jardine Matheson and/or its subsidiaries from financing due to climate and environmental concerns, according to data from the Financial Exclusions Tracker.

The fund said the decisions are based on a recommendation from its ethics council, which found “an unacceptable risk that they are contributing to or are themselves responsible for serious environmental damage.”

The council made the recommendation in 2023 after assessing the environmental impact of the Martabe gold mine concession in the northern part of Indonesia’s Sumatra Island. Jardines bought the mine in 2018 through its Indonesian subsidiary, Astra International, the largest conglomerate in the Southeast Asian country. The mine, in turn, is operated by an Astra International subsidiary, PT Agincourt Resources (PTAR), and is located inside the Batang Toru forest, the only known habitat of the critically endangered Tapanuli orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis).

A baby Tapanuli orangutan looking for food in the Batang Toru forest, North Sumatra, Indonesia, in September 2018. Image courtesy of Prayugo Utomo/Wikimedia Commons.

The ape was only described as a new species in 2017, but it’s already the most threatened great ape with fewer than 800 individuals.

These apes survive in a tiny tract of forest less than one-fifth the size of the metropolitan area that comprises Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta, as they have lost 95% of their historical habitat due to hunting, conflict killing and agriculture.

This means that the survival of the species depends on the preservation of this habitat, and any further reduction would inevitably increase the threat to the ape population.

The fund’s ethics council worried that the continued expansion of the Martabe gold mine will do just that.

The Martabe mining area lies in the portion of the orangutan’s habitat with the largest orangutan population, where the probability of the species’ long-term survival is highest.

The council pointed out that Agincourt is planning to significantly increase the mining area during the mine’s lifetime, as the company is committed to exploiting new deposits if commercially viable.

Furthermore, the Indonesian authorities have granted permission for mining operations in undeveloped area as well, the council added.

“The Council considers that, as long as PTAR’s activities result in a reduction in the size of the orangutan’s habitat, the risk of the companies contributing to serious environmental damage will remain unacceptable,” the council said in a statement.

Responding to the fund’s decision, Jardines said it was “disappointed.”

“We recognise that the longterm survival of the Tapanuli orangutan is of the utmost anthropological significance and each of Jardines, Astra, UT and PTAR are committed to supporting the conservation of this species,” the conglomerate said.

This commitment, however, is still not enough, the council said.

“The company’s efforts to preserve these orangutans does not to any great degree seem to be limiting the mine’s expansion or prospecting deeper into the orangutans’ habitat,” the council said.

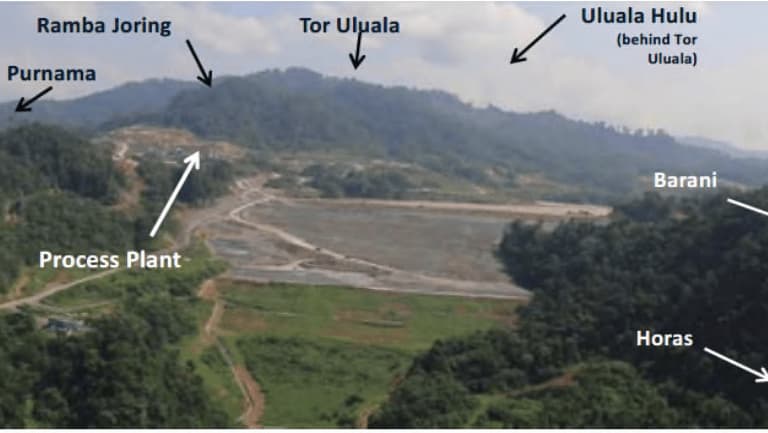

The Martabe gold mine in Batang Toru, North Sumatra, Indonesia. Image courtesy of Agincourt Resources.

Expansion

Most recently, the biggest concern comes from a plan by Agincourt to look for new gold reserves at a new site north of the current mine, covering a total area of around 1 hectare (2.47 acres). The new site is located in an area called Tor Ulu Ala (TUA), which has been recognized by the conservation group Alliance for Zero Extinction (AZE).

All confirmed AZE sites such as the TUA area qualify as Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) because they “hold a significant proportion of the global population size of a species facing a high risk of extinction, and so contribute to the global persistence of biodiversity at genetic and species levels.”

The new exploration entails the drilling of boreholes at 16 sites, each approximately 25 meters by 25 meters (82 feet by 82 feet), within 1 hectare of area. Agincourt initially proposed an exploration area of 3.1 hectares (7.7 acres), covering 50 drilling sites.

The location of the Martabe gold mine and the areas in which prospecting (trial drilling) is taking place. The Purnama Pit, Barani Pit and Ramba Joring deposits are in operation. Image courtesy of Agincourt Resources.

Agincourt said the exploration has been designed to be as low-impact as possible on the surrounding environment. Agincourt has consulted a team of four orangutan and conservation experts hired by the company called the biodiversity advisory panel (BAP).

However, a 2003 environmental survey on the Martabe gold mine found a significant correlation between the intensity of trial drilling and a decline in orangutan density.

The survey was commissioned by PT Newmont Horas Nauli, which owned the mine at that time, and it assessed the project’s impact on the orangutan population.

According to the survey, even though the company took steps to minimize the mining activity’s disturbance of the forest, the effect on the orangutan population was “considered significant enough to have forced at least temporary relocation of some orangutans, resulting in a lower number of orangutans in the Martabe Project area at present.”

Due to the fragile ecosystem of the northern part of the mine, the ARRC Task Force — a unit of the Primate Specialist Group under the global wildlife conservation authority IUCN, has recommended that Agincourt avoids going to the north to find new reserves.

Now that the Norwegian fund has excluded investments in Jardines, the conglomerate should reconsider the plan to go north, said Amanda Hurowitz, the senior director for Asia at U.S.-based campaign group Mighty Earth.

“We hope this is the wake-up call Jardines needs to seriously reconsider its plans to expand the Martabe mine into habitat which is crucial to securing a future for the Tapanuli orangutan, the world’s rarest great ape,” she said.

Agincourt described the new exploration as “essential” to decide whether to proceed with future development or not.

Under Agincourt’s 30-year work contract with the government, the company is legally obligated to continue looking for commercially viable deposits within its concession area.

At a meeting with the Norwegian fund’s council, Agincourt disclosed that it will exploit all commercially viable deposits, but not deposits in areas that have formal protected status.

As of January 2022, Agincourt’s mining area covered just more than 509 hectares (1,258 acres), which used to be forested areas. The mining area is expected to keep expanding to 918 hectares (2,268 acres), nearly double the current footprint, during the mine’s productive life.

According to Agincourt’s 2022 annual report, the Martabe gold mine has a remaining life of mine of around 11 years.

As Agincourt’s mining and exploration areas continue to grow, so does forest loss within its concession.

The mine’s operation resulted in the clearance of 100 hectares (247 acres) of forest from 2016 to 2020.

In 2021 and 2022, Mighty Earth detected further forest loss within the mining concession.

Tapanuli Orangutans found near YEL’s orangutan study camp in the Batang Toru forest. Image by Aditya Sumitra/Mighty Earth.

Mitigation

To mitigate the mine’s impact on the Tapanuli orangutan and determine the apes’ population density in the mining area, Agincourt has taken a number of actions.

For one, it said it had implemented a biodiversity action plan, which includes programs to minimize conflicts between orangutans and humans in connection with forest clearance.

And prior to any land-clearing activities, the BAP has to carry out preclearance surveys. No development work proceeded until the BAP confirmed there was a low risk of harm to the Tapanuli orangutan and its habitat, Agincourt said.

After the company is finished mining, it will replant the mine area to mitigate the loss of habitat for the orangutans.

Agincourt and the BAP have also carried out extensive surveys and environmental impact assessments, including an orangutan impact assessment study in 2021.

According to Agincourt, the study concluded that “while habitat loss is the main potential impact on the Tapanuli orangutans, this impact can be mitigated through biodiversity management measures implemented during the life of the mine and through the ongoing rehabilitation of land, all of which are measures PTAR is taking or will take, taking account of the advice and input from the BAP.”

Agincourt also claimed that the orangutan population density in the mining area is low, even though the apes “may use part of the mine seasonally for nesting and foraging.”

The ethics council said it hasn’t had access to any of the studies the company has performed due to restrictions imposed by the Indonesian authorities. The companies have disclosed that the Indonesian authorities must authorize any sharing of the underlying study data and research results with foreign researchers or organizations.

Therefore, the council said it had no basis on which to assess the measures undertaken by the company.

This information restriction has also prevented the IUCN’s expert group, the ARRC, from evaluating the company’s investigations and mitigation measures, even though the task force had an agreement to work together with the company in 2022 to conserve the orangutan.

This restriction is “not in accordance with the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’s goals with respect to information sharing,” the ethics council noted.

The Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Walhi), the country’s biggest green NGO, welcomed the Norwegian fund’s decision, saying that it could help preserve the Batang Toru ecosystem.

Walhi forest and plantation campaign manager Uli Arta Siagian pointed out that the region is not only important for the survival of the Tapanuli orangutan, but it is also home to five watersheds that provide water for 100,000 people as well as critical wildlife habitat for several critically endangered and endangered species, such as the pangolin (Manis javanica), the helmeted hornbill (Rhinoplax vigil) and the Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris).

The 2003 environmental survey of the Martabe project identified 15 globally endangered species and more than 60 species that were near threatened (largely birds, but also some primates) in or near the project area. Eleven plant species new to science were also discovered in connection with the survey.

“Creditors and investors must stop providing financing to companies that threaten our forests, communities and biodiversity,” Uli said.

Banner image: A Tapanuli orangutan in Batang Toru forest, North Sumatra, Indonesia, in April 2022. Image cortesy of Dimasmhd/Wikimedia Commons.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay