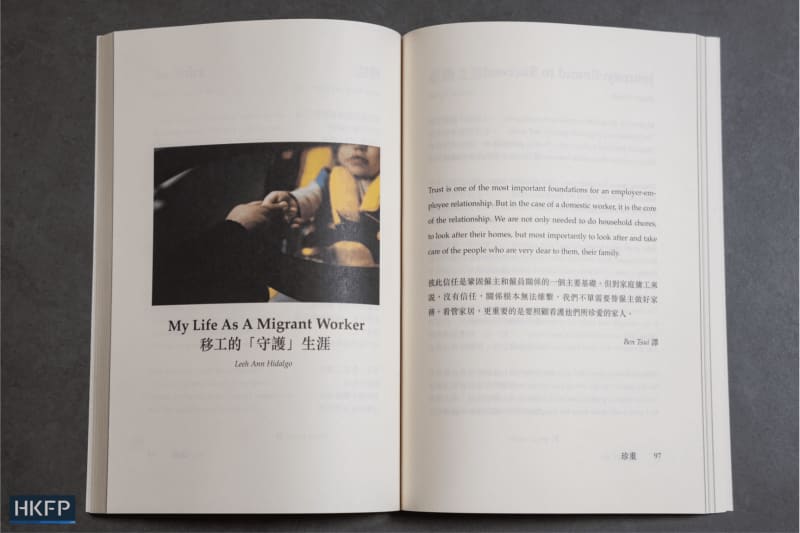

Ingat, an anthology by domestic workers in Hong Kong. Photo: Kyle Lam/HKFP. Used with permission.

This report was written by Hillary Leung and originally published in Hong Kong Free Press (HKFP) on March 9, 2024. An edited version is published below as part of a content partnership agreement with HKFP.

Maria Editha Garma-Respicio fondly recalls her teenage years writing for her school newspaper, reading in the library and penning poems about love. Growing up in Tuguegarao, a city in the northern Philippines, she sought solace in the written word when all else seemed to be falling apart.

“I wrote about everything,” Respicio, as she asked to be called, said. “I wrote about my emotions, being in love, everything.”

Decades later, writing continues to play a central role in Respicio’s life. The 45-year-old domestic worker in Hong Kong writes poems about life as a migrant worker, her two children back home and whatever inspires her at the moment.

“Writing is a kind of therapy for me,” Respicio told HKFP. “It’s healing.”

Respicio’s poetry has been published in a number of literary magazines. Most recently, two of her poems found a home in “Ingat”, a new anthology of poetry, photographs and sketches by the city’s migrant workers.

Released last Sunday, “Ingat” — meaning “take care” in Tagalog — is a collaborative effort by Migrant Writers of Hong Kong, photography nonprofit Lensational and independent publisher Small Tune Press. It features the work of dozens of domestic workers telling stories about family, hardship, love and sacrifice.

All the works in the book are accompanied by Chinese translations to make it more accessible to Hong Kong readers. The anthology’s dust jacket pays tribute to balikbayan boxes, or large cardboard boxes stuffed with food, clothes and other gifts that domestic workers send home to their families.

The city’s 340,000 domestic workers, mostly from the Philippines and Indonesia, are the backbone of many Hong Kong families. Research has shown that domestic workers contribute significantly to the city’s economy, freeing up parents from childcare and other duties so they can enter the workforce.

Migrant worker activists have long campaigned for their rights, citing cases of domestic workers being denied rest days, food, or their salaries.

Respicio wrote two poems for the anthology: “Diaspora Spirit” and “Adios”. The first is a tribute to the courage of migrant workers, while in the second, she describes a tearful farewell to her family in the Philippines:

Goodbye’s a torture, my tears shedding / I’ll no longer witness my baby’s milestone / Others children I will be caring / Making me numb like an ice stone

Christine Vicera, one of the leaders of the project and co-founder of be/longing, an initiative supporting ethnically diverse communities, said the book aimed to carve out space for work that is “often forgotten or not as visible” on Hong Kong’s creative scene.

Born in the Philippines but having moved to the city as a toddler, Vicera — who co-edited the anthology — said she always wished there was more diversity in the literary scene:

Growing up, I’ve always wanted to see works by people in our communities on bookshelves. People from Hong Kong, people who are Filipino and of course, people who are migrant domestic workers.

‘A very powerful story’

Established in 2021, Migrant Writers of Hong Kong unites domestic workers with a common love for the written word. The group partners with universities to organise writing workshops, poetry exhibitions and arts events on Sundays, the sole day off for most domestic workers.

Maria Nemy Lou Rocio co-founded the group after being inspired by Migrant Writers of Singapore. Noting the absence of such a community here, the 42 year old set out to create a safe, inclusive space for domestic workers in Hong Kong to share their creations and hone their craft. Rocio, who has been a migrant worker in Hong Kong for six years, told HKFP:

Migrant workers are very talented. Every poem they write is a very powerful story.

Shortly after establishing Migrant Workers of Hong Kong, Rocio told Vicera that she wanted to produce an anthology to showcase the writing of domestic workers. The idea was soon expanded to spotlight not just written work but photos, art and other mediums.

Kristine Andaya Ventura’s contribution to “Ingat” is a sketch of a couple paddling a boat under the full moon. The 36-year-old Filipina has been working overseas as a domestic worker since she was 19, first in Lebanon and then in Saudi Arabia, Dubai and Malaysia. She came to Hong Kong at the end of 2022:

[My sketch] is about two hearts saying goodbye. No matter how happy they are today, tomorrow they need to say goodbye to separate, to have a good future.

Ventura is as much a writer as she is an artist, having penned dozens of poems over the years. She published a book of her poetry called “She is a Lioness” in 2021, telling stories about heartbreak over a failed marriage, battling depression, and life as a domestic worker in a foreign land.

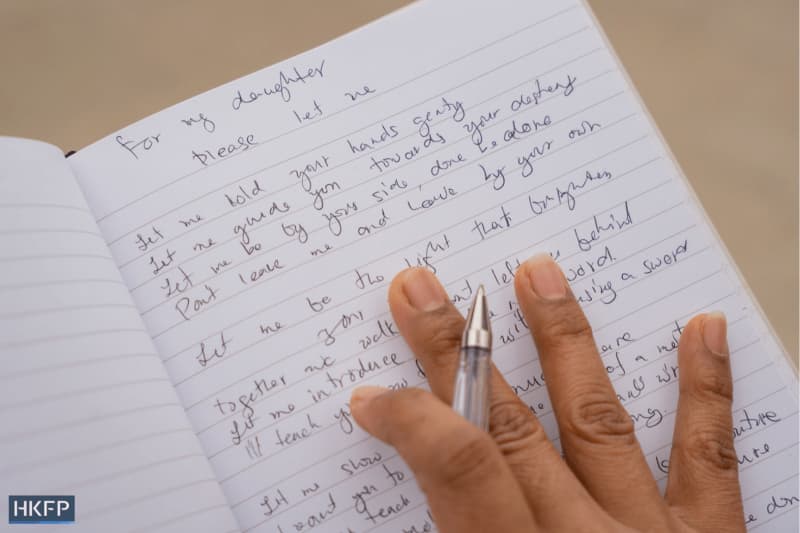

Her main writing inspiration, she said, was her two children, aged 8 and 17:

I want to dedicate [my poems] to them [to show] how I love them and miss them,” Ventura said. “When I miss them, I will express that I need to work outside the country for them… to give them financial support… Writing also helps me ease the pain.

A poem that Kristine Andaya Ventura dedicated to her daughter called “Please Let Me.” Photo: Kyle Lam/HKFP. Used with permission.

Besides poems, “Ingat” also features around two dozen photos taken by members of Lensational, a non-profit that supports domestic workers interested in photography.

Felicia Xu, a volunteer at Lensational who curated the photo submissions, said photography was a powerful tool for migrant workers as it transcended the barriers of language.

Years ago, Lensational ran an event inviting domestic workers and their employers to view their work, she told HKFP. Some of the employers became emotional when they talked to their domestic workers, Xu said:

When [one of the employers] saw the photo, it raised her interest and she started asking questions. She got to know the struggles of the domestic worker that she basically spends every minute with, but she didn’t know anything about her emotions… and that photo broke the ice.

Defying stereotypes

For the migrant workers who contributed to the anthology, writing poems and taking photos is a way for them to express their emotions and prompt society to seek new perspectives.

A study by researchers at Lingnan University last year found that domestic workers were unfairly represented by the city’s media outlets. According to an analysis of almost 400 reports about the mistreatment of domestic workers in Chinese-language media, outlets tended to use language that highlighted the “positive personality traits” of employers.

The anthology’s launch also comes as the government continues to crackdown on what it calls domestic workers’ “job-hopping”, or prematurely ending their contracts to change employers. The government is slated to announce new rules by July that could make it harder for domestic workers to switch employers.

Vicera said influencing policy-making was tougher nowadays as the legislature lacked lawmakers who campaigned for domestic workers’ rights.

Since authorities overhauled the electoral system in 2021, only people deemed “patriots” by the government can run in leadership races. During previous legislature terms, when there was still an effective opposition, pro-democracy lawmakers worked with NGOs and activists to lobby for domestic workers’ interests.

Under these circumstances, visibility through projects such as “Ingat” is more important than ever.

Written by Hong Kong Free Press

This post originally appeared on Global Voices.