By Carla Ruas

At Belén Market in the northeastern Peruvian city of Iquitos, monkeys illegally captured from the Amazon Rainforest are sold as pets right next to fruits and vegetables. The primates are kept in tight cages and in close contact with other animals, people and trash — ideal conditions for picking up and spreading diseases.

But markets like Belén are only the beginning, according to a recent paper published in PLOS ONE. The monkeys continue to transmit viruses, parasites and bacteria all along the trafficking route, even as they reach their final destinations in households, or rescue centers and zoos if local authorities seize them.

Scientists estimate hundreds of thousands of primates are captured and trafficked annually in Peru. While some are traded for food, artifacts and remedies, most are sold alive and locally as pets. According to a recent survey by World Animal Protection, 40% of Peruvians living in cities have admitted to purchasing wild animals as pets.

When local authorities confiscate trafficked monkeys, they take them to zoos and rescue centers. Image courtesy of Patricia Mendoza /Neotropical Primate Conservation–Peru.

The most popular trafficked species are tamarins (from the genera Saguinus and Leontocebus) and squirrel monkeys (Saimiri), which sell for as little as $10. At the other end of the scale, species like Goeldi’s monkey (Callimico goeldii) are sought-after on the international black market and can cost up to $900.

For the recent study, researchers tested 388 monkeys that had been illegal trafficked in nine Peruvian cities, and found a total of 32 disease pathogens in their blood, saliva and fecal samples. These pathogens included mycobacteria, which causes tuberculosis, and parasites that cause Chagas disease, malaria and various gastrointestinal ailments. Combined, these diseases kill more than 1.4 million people every year globally.

“When we bring animals from the wild to the cities and put them into places of captivity, we are bringing along various disease agents,” said study lead author Patricia Mendoza, an anthropologist at Washington University in the U.S. and researcher with USAID’s Emerging Pandemic Threats (PREDICT) program. “It’s not only new viruses such as COVID-19 that we are concerned about. Many known infectious diseases can be easily transmitted through trafficked animals.”

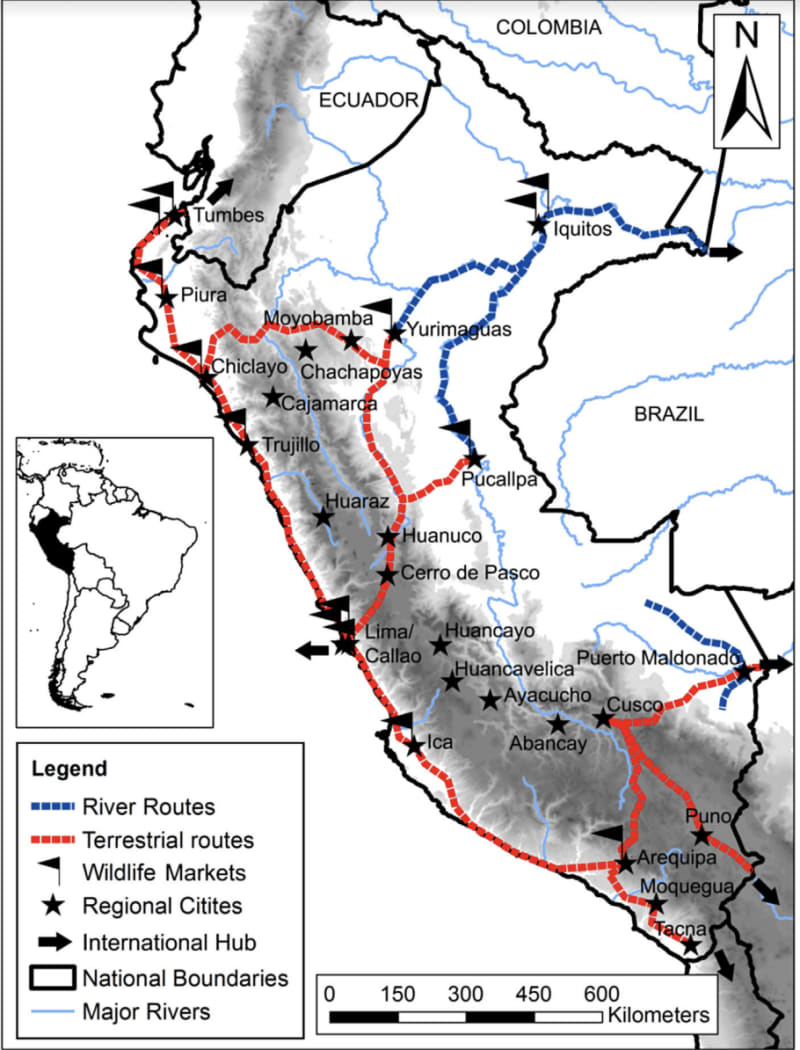

Major trafficking routes for the illegal trade of primates in Peru. Map courtesy of Shanee et al.

The monkeys tested in street markets were still carrying hemoparasites found in the Amazon Rainforest, including the parasite that causes malaria. However, as the monkeys were moved to other smuggling sites, they acquired other pathogens, such as the antibiotic-resistant bacteria Shigella sonnei, which in people can cause bloody diarrhea, fever and stomach pains.

Throughout the entire trafficking route, humans exposed to these animals were at constant risk of infection. “At these markets, thousands of people are circulating, and there’s a high risk of transmission,” Mendoza told Mongabay. “But in households, people sleep [with], hug, and kiss monkeys. The one-to-one contact is very close, endangering these families.”

2. Map of Peru showing the location of markets permanently selling live wildlife (red pins) or only domestic animals (green pins). Map courtesy of Mendoza et al.

Even zoos and rescue centers, where primates are often taken when confiscated by local authorities, aren’t free from contamination. “They are doing their best to keep animals healthy and well cared for. But infections are common, no matter how much emphasis they put on screening for parasites,” Mendoza said.

While researchers initially tested birds and turtles, monkeys stood out as a particularly dangerous avenue of transmissions. They’re among the most trafficked animals in Peru, and their DNA is, on average, 96% identical to that of humans. That makes them more likely than other animals to spread diseases that can affect humans.

Climate change increases risk of zoonotic transmission

Scientists say wildlife traffickers and their families are most at risk of picking up diseases from trafficked monkeys. They’re are commonly bitten, scratched and exposed to animals’ feces. A similar transmission pattern has been found among hunters in the Peruvian Amazon who interact closely with wildlife.

However, infected primates can disseminate diseases more broadly. They carry parasites that mosquitoes can pick up and spread to the surrounding community. Yellow fever, cutaneous leishmaniasis and even new strains of malaria are transmitted this way.

Tamarins are popular pets among Peruvians and can be bought for as little as $10. Image courtesy of Patricia Mendoza/Neotropical Primate Conservation–Peru.

“This is a matter of public health,” said Alessandra Nava, a researcher with the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Brazil’s leading public health research institute. “Illegal wildlife trade is forcing animals to live beyond their home range, where they are introducing a whole reservoir of new viruses, bacteria and parasites.”

The risk of transmission via mosquitoes is accelerating due to climate change. As temperatures rise, mosquitoes are advancing into new areas, becoming more active and incubating more disease. In Peru alone, the mosquito population has exploded in recent years, fueling an alarming spread of dengue fever.

Monkeys also at risk

The exchange of pathogens with humans also threatens monkeys caught up in the illegal pet trade. New diseases can burden species already threatened by hunting and habitat loss, including Goeldi’s monkey, classified as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List.

If infected primates are reintroduced to the wild, there’s also a possibility they could spread these diseases to other species.

Wildlife trafficking hurts primates in many other ways.

Researcher Patricia Mendoza led the study that tested 388 monkeys that were trafficked in Peru. Image courtesy of Fernando Vilchez.

“When these animals are captured from the Amazon forest, there’s a lot of suffering and stress for them,” said Roberto Vieto, global animal welfare adviser at World Animal Protection. “Sometimes, hunters will kill the parents looking for the babies that are more desirable in the pet market, and the methods of killing them are extremely cruel.”

Once abducted, the monkeys go on long journeys in small boxes or cages to remain undetected by local authorities. Some are taken across the border to Ecuador and Bolivia and smuggled onward to Europe, China and the United States. “Many do not survive the trip, and there’s a high mortality rate,” Vieto told Mongabay.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, environmentalists expected the Peruvian wildlife trade would slow down. Many street markets closed or reduced operations, and vendors became wary of openly selling wildlife. However, the lull didn’t last. “The illegal wildlife trade came back as business as usual,” said Vieto, who worked on the 2021 WAP report “Risky Business: How Peru’s wildlife markets are putting animals and people at risk.”

Alessandra Nava, a researcher with the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, believes animal trafficking is a matter of public health. Image: Archive/ Fiocruz Amazônia

Vieto said he’s hopeful that new legislation will finally curb the illegal activity. Since November 2022, animal trafficking has fallen under the Law Against Organized Crime, with harsher penalties. “We already see authorities paying more attention,” Vieto said. “But we need to do more helping those involved with trafficking to have sustainable livelihoods that don’t depend on hurting wild animals.

Citation:

Mendoza, A. P., Muñoz-Maceda, A., Ghersi, B. M., De La Puente, M., Zariquiey, C., Cavero, N., … Rosenbaum, M. H. (2024). Diversity and prevalence of zoonotic infections at the animal-human interface of primate trafficking in Peru. PLOS ONE, 19(2), e0287893. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0287893

Banner image: Trafficked primates can spread viruses, parasites and bacteria all along the trafficking route. Image courtesy of Patricia Mendoza/Neotropical Primate Conservation–Peru.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay