By Petro Kotzé

Toilet paper is so common in some countries it’s only noticed when it’s not there, as exemplified by the panic buying that prompted shortages when the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020.

Thought to be in use in China since the sixth century, inventor Joseph C. Gayetty patented the first U.S. commercial “medicated paper” in the 1850s. Since then, demand has soared in many places, bolstered by rising population, urbanization, shifts in demographics, changing hygiene practices, and lifestyle choices influenced by advertising.

Still, only 25-30% of the world uses TP today; the rest rinse with water or use other means. Regardless, by 2023, yearly revenue in the toilet paper sector (dry and wet toilet paper) totaled $107.4 billion, with sales of nearly 46 million metric tons, a market expected to grow annually planetwide by 5.92%. The most revenue is generated in populous China, amounting to $22.33 billion in 2023, where growth is forecast at 7% per year until 2027, according to Statista analyst Apurva Janrao.

With so much TP flying off the rolls, “People need to start thinking about [the sector’s] environmental impact,” says AidEnvironment researcher Okita Miraningrum.

Those adverse effects pop up along the entire supply chain, from sourcing in native forests and on eucalyptus plantations; to energy-, water- and chemical-intensive manufacturing practices; to transport and packaging; and to the final flush, after which waste TP can tax sewage treatment facilities. A big red flag: the link of some toilet paper sourcing to the loss of old-growth forests.

The Canadian boreal forest is one of the world’s last large remaining intact forests, home to multiple Indigenous communities and rich in biodiversity. But provincial and national regulations continue to allow it to be cut for pulp, some of which is used to make toilet paper. Image courtesy of River Jordan for NRDC.

Deforestation: The hard reality of soft toilet paper

In concept, toilet paper is simple. It’s made of cellulose fibers plus chemicals to glue it together, explains industry expert Greg Grishchenko, a retired mechanical engineer who spent more than four decades in the tissue production industry. The fibers are mostly sourced from trees, but can also come from recycled paper or alternative sources like bamboo.

However, Grishchenko emphasizes that to make the softest, whitest TP — qualities cherished by more and more consumers — you need virgin pulp, made from forest or plantation trees. (The more the paper is recycled, he explains, the shorter the fibers become and the less usable they are.)

As the demand.) for high-quality, soft, absorbent toilet paper rises among customers focused on hygiene, cleanliness and comfort, sourcing from trees, forests and plantations is set to increase, say analysts. Meanwhile, environmentalists caution that the need for virgin pulp is having dire consequences and, according to the Natural Resource Defense Council, already “taking a substantial toll on forests around the world.”

When AidEnvironment, a research consultancy, noticed more deforestation in Indonesia was taking place for timber, pulp and paper than for palm oil, it launched an investigation into the world’s tissue paper companies and their forest management practices, says AidEnvironment program director Christopher Wiggs. Their report notes that as of 2020, Brazil, Canada, the U.S., Indonesia and Chile are the world’s largest pulp exporters.

Alternative fibers for pulp to make toilet paper can decrease environmental impact. Essity’s straw pulp plant in Germany was inaugurated in 2021. Image courtesy of Essity.

The trouble with plantation-sourced TP

Eucalyptus plantations in Brazil, the largest exporter of pulp suitable for tissue production, are known worldwide for providing the best-quality fiber, critical for tissue softness, and for premium-quality products offered at higher profits. In 2020, Brazil exported 15.6 million metric tons of pulp as part of an expanding tissue production and export industry. Nearly 48% went to China, about a quarter to Europe, some 15% to the U.S., and the rest to other countries.

The rapid expansion of eucalyptus plantations in Brazil and elsewhere has divided environmentalists. A few support pulp exporters’ claims that eucalyptus plantations help curb the global climate crisis by storing carbon. Others note this carbon storage is only for a limited time, with trees cut and pulped every eight years or so. The use of native trees to make pulp, or their cutting to establish plantations also promotes deforestation.

Other problems arise because invasive eucalyptus, a tree native to Australia, is a water hog and rapidly sucks up groundwater, intensifying water loss in countries like Brazil, or in Africa, where climate change-driven drought has become a serious problem. Eucalyptus plantations also lack species richness. In addition, if the trees are treated with synthetic chemical pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers, they can pollute groundwater. Lastly, pulpwood companies in Brazil have been accused of expelling traditional and Indigenous people from their claimed lands, and of other inequities.

Active clearance and drainage of peatland rainforest in a concession run by PT Asia Tani Persada, which is also an orangutan habitat. The company, affiliated with Indonesian conglomerate Sinarmas, is a supplier of pulpwood to Asia Pulp & Paper. Greenpeace has called on Indonesian citizens and the government to protect Indonesia’s forest from this destruction. Image © Ulet Ifansasti/Greenpeace.

In Canada, the world’s second-largest pulp exporter, industrial logging, including for pulpwood, is taking place in some of the world’s last remaining old-growth boreal forest, home to Indigenous communities, as well as caribou, pine marten and billions of songbirds. Industrial logging is reportedly claiming more than a million acres of boreal forest annually, much of this driven by the need for pulp. Canada is the world’s largest producer of northern bleached softwood kraft (NBSK) pulp, favored for virgin pulp tissue production. Approximately half of Canada’s NBSK pulp goes to making tissue products.

U.S-.based paper companies are under consumer pressure to decrease their use of virgin wood pulp, especially from Canadian boreal forests. Kimberley-Clark, for example, one of three tissue companies with the largest U.S. market share, has set a target to reduce its use of natural forest fibers (primarily from northern boreal and temperate forests), by 50% by 2025 compared to a 2011 baseline. Its website calls this goal “challenging,” but when asked why, company spokesperson David Kellis could add no further details.

Tropical rainforests in Indonesia and Malaysia are also being logged or converted into plantations to produce pulp. A 2023 Greenpeace report found that one of the world’s largest pulp and paper companies, Indonesia’s Royal Golden Eagle (RGE) Group, has a pulp mill in China that uses wood from companies known to have cleared large tracts of tropical rainforest and endangered orangutan habitat in Kalimantan, the Indonesian portion of the island of Borneo.

Though Greenpeace could not link the tissue industry directly to active deforestation, Wiggs says AidEnvironment found the timber and paper industry lacking in the enhanced transparency found more recently with palm oil buyers. “There’s very little transparency,” he says.

This aerial image shows the impact of logging in Canada’s boreal forests. Image courtesy of River Jordan for NRDC.

A canal constructed in peatland forest inside a pulpwood concession in Indonesia. Cleared and drained carbon-rich peat becomes dry and vulnerable to fires. Image courtesy of Ulet Ifansasti/Greenpeace.

Powering the production of toilet paper

Toilet paper’s largest environmental impact, according to some research, derives from the massive amount of electricity needed by manufacturing facilities to heat pulp, water and chemicals, and then to dry the resulting rolls of paper.

Carbon emissions from such plants, of course, depend on how each is powered — whether from the electrical power grid, or a mill heat source — and if the electricity comes from fossil fuels or sustainable choices. The energy efficiency of factory machinery also plays a role.

A Poland-based study, where the power grid is mostly reliant on coal, found that the largest overall environmental impact of toilet paper production (for both virgin and recycled pulp) comes from electricity use, along with considerable water emissions, solid waste, and air pollution.

As awareness of the environmental impacts of toilet paper increases, companies are offering greener alternatives, but the environmental footprint of toilet paper is complex and requires action to make it sustainable along its entire supply chain. Kimberly-Clark, for example committed to reduce its environmental footprint by 50% by 2025, in part by using more non-wood fibers in its tissue products. Kleenex Eco was the firm’s first 100% bamboo product. Who Gives a Crap and other entities have focused on high-priced eco-friendly tissue products as a niche market. Image courtesy of Kimberly-Clark.

Cottonelle toilet paper is a luxury brand made by Kimberly-Clark, one of the largest U.S. tissue companies. The company has committed to reducing its use of natural wood fibers (primarily from northern boreal and temperate forests) by 50% by 2025 compared to a 2011 baseline. The firm’s website calls this goal “challenging,” but when asked why, a company spokesperson could add no further details. Image courtesy of Kimberly-Clark.

After the flush

Toilet paper impacts accumulate as the product is packaged and transported, and finally used and disposed of.

A study published by the American Chemical Society last year found that toilet paper should be considered a “potentially major” source of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) entering wastewater treatment systems. With multiple adverse health effects in humans and wildlife, these “forever chemicals” are added when converting wood into pulp. Recycled toilet paper, too, can be made with fibers that come from materials containing PFAS.

Others note that toilet paper is one of the major insoluble pollutant components released into wastewater treatment plants. The fibers are a troublesome component of sewage sludge, requiring a high treatment cost and high energy use. In countries without waste treatment facilities, toilet paper can end up entering directly into waterways.

Clearing natural forest in a deep peatland area for a pulpwood concession in North Kalimantan province, Indonesia. The biggest driver of deforestation related to toilet paper production is now emerging markets, particularly Asia. Image © Ulet Ifansasti/Greenpeace.

Lightening the load of toilet paper use

Reducing all these environmental impacts requires action by a variety of actors working along the supply chain, with solutions as varied and complex as the industry itself.

A first TP solution is to install and use a bidet, which squirts a spray of water to clean the behind. A life-cycle assessment found bidets to have a lower environmental impact than toilet paper in categories ranging from climate to human health, resource and ecosystems (but not water). Other researchers have pointed out that the logic of such a switch depends on local water availability and sanitation systems.

A second alternative is to use less toilet paper, and falls on individual consumers. Janrao of Statista notes that Europeans and U.K. residents lead in toilet paper consumption. Others point out that U.S. households use three rolls a week on average.

A third possibility: make the switch to recycled paper. A comparison of manufacturing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from toilet paper made from virgin pulp and recycled fiber showed that, though demands for both thermal energy and electricity are higher for recycled paper during manufacturing, GHG emissions from virgin pulp are about 30% higher than from recycled paper (emitting 568 kilograms of CO2 equivalent more per kilogram of tissue paper) because of the added impact of wood pulping.

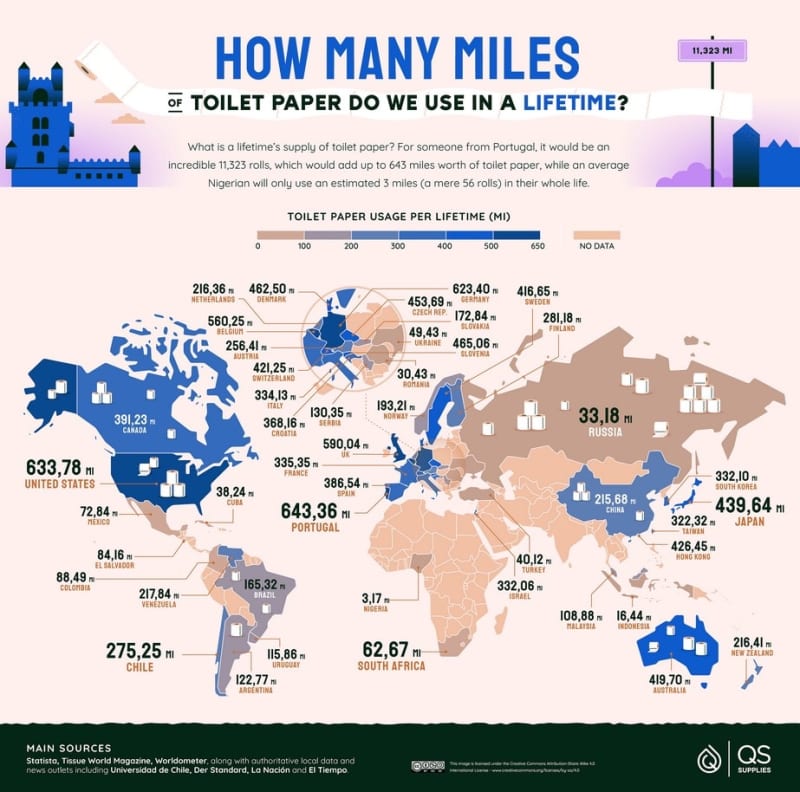

How many miles of toilet paper do we use in a lifetime? Large parts of the world use little or no toilet paper. Image courtesy of Q&S Supplies.

Toilet paper made from alternative sources like bamboo or sugarcane are also gaining attention. However, Grishchenko points out that many non-wood fiber brands are sourced in Asian countries, including China and India, and shipping to users halfway round the globe in the U.S. or EU generates a large carbon footprint.

Innovative alternative tissue sourcing is also being done closer to most TP consumers. Essity, for example, among the world’s nine largest tissue paper manufacturers, inaugurated a facility to produce pulp from wheat straw at its Mannheim, Germany, factory in 2021, says Michaela Wingfield, the firm’s central region communications director. This breakthrough technology uses less water and energy in production. “Initial calculations indicate that the unique Essity straw pulp has a 20% better environmental footprint than tissue made from wood fibers,” Wingfield says. The tissue is also as soft, white and strong as that made from wood fiber.

Other environmentally sound manufacturing initiatives include installation of onsite co-generated heat and power to decrease reliance on the national power grid.

Essity’s straw pulp factory produces soft, white and strong tissue with a lower environmental footprint than that made from wood pulp, including from eucalyptus trees. Image courtesy of Essity.

Western companies with more sustainability-aware customers are cleaning up their act, AidEnvironment’s Wiggs says. The biggest driver of deforestation now, he notes, is in emerging markets, particularly Asia. According to the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization, consumption of wood pulp has slowed in recent decades, mainly due to decreasing consumption of newsprint, writing and graphics papers. Instead, in future, demand for pulp will likely be driven by the need for packaging and hygienic tissues in Asian, EU and Northern American markets. They note that the most significant market growth is expected to occur in the Asian subregions, where production capacities for wood pulp have increased “massively” since 2000.

Environmentally sound policies and regulations need to be applied across the whole pulp and paper industry, and in countries where it operates, AidEnvironment’s Miraningrum says. Wiggs adds, “the immediate goal would be more transparency in the timber industry.” Critics are also calling for more awareness by civil society, meaning that, perhaps, it’s time to bring toilet paper into the conversation.

Banner image: Industrial logging reportedly clears more than a million acres of boreal forest in Canada annually. Paper companies working there are under public pressure to decrease their use of virgin wood pulp. Image courtesy of River Jordan for NRDC.

Citations:

Masternak-Janus, A., & Rybaczewska-Błażejowska, M. (2015). Life cycle analysis of tissue paper manufacturing from virgin pulp or recycled waste paper. Management and Production Engineering Review, 6(3), 47-54. doi:10.1515/mper-2015-0025

Thompson, J. T., Chen, B., Bowden, J. A., & Townsend, T. G. (2023). Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in toilet paper and the impact on wastewater systems. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 10(3), 234-239. doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.3c00094

Wang, X., Liu, G., Sun, W., Cao, Z., Liu, H., Xiong, Y., … Gao, P. (2023). Removal of toilet paper fibers from residential wastewater: A life cycle assessment. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(35), 84254-84266. doi:10.1007/s11356-023-28291-5

Gemechu, E. D., Butnar, I., Gomà-Camps, J., Pons, A., & Castells, F. (2013). A comparison of the GHG emissions caused by manufacturing tissue paper from virgin pulp or recycled waste paper. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 18(8), 1618-1628. doi:10.1007/s11367-013-0597-x

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay