By Didier MakalLatoya Abulu

LUBUMBASHI, Democratic Republic of the Congo — Land grabbing, lack of consultation, communities wiped off maps, and impunity. These are the serious accusations made against the mining company Alphamin Bisie Mining SA by the Indigenous communities of Banamwesi and Motondo, which oversee community forest concessions in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Years of complaints by these communities and civil society organizations have been met with no reaction from provincial government officials or the mining company. Alphamin Bisie, which runs a tin mine neighboring the communities, has not responded to them and does not recognize them as affected. In light of the conflict devastating the eastern DRC, the Indigenous inhabitants say the conflict is being used as a cover for the irregular activities taking place around them.

“They are continuing to claim their rights because the [company’s] land occupation did not comply with the normal process,” said Fiston Misona, a leading member of civil society in Walikale, in a call with Mongabay.

Despite Mongabay’s inquiries, the administrative authorities did not respond to requests for information and documentation on activities at the Bisie tin deposit. After nearly a year of attempts to reach the mining company, Alphamin Bisie finally responded to explain their position and deny the communities as the landowners. But answers did not put to rest allegations and findings that irregular activities are taking place.

This area, covered with lush forests and savannahs ideal for Indigenous communities’ agropastoral activities, has all the makings of an Earthly paradise. This has especially been the case since strategic minerals such as cassiterite, coltan (columbite–tantalite), and gold were discovered in Walikale’s subsoil. The territory’s rich biodiversity, a defining aspect of the Congo Basin, is managed by Indigenous Twa people through local community forestry concessions (CFCLs) securing their land rights on plots of land. The establishment of these concessions is part of a government strategy to involve communities in the sustainable management of forests and to reduce poverty.

However, this territory in particular has witnessed the emergence of several armed groups and repeated clashes with the government forces trying to fend them off.

Situated 180 kilometers (112 miles) from Goma, the capital of the Congolese province of North Kivu, Walikale is located in a martyred region of the eastern DRC. About a hundred armed groups have been active here since the Rwandan genocide of 1994, which has been followed by continued instability and insecurity over two decades later. The presence of these natural resources, which are highly sought after in industrialized countries for their importance in the electronics industry, continues to fuel violence and finance these armed groups.

Nowadays, the province is run by a military governor, Constant Ndima, whom members of civil society said is focused on the armed conflict and doesn’t seem to pay attention to civil claims. This has created an atmosphere in which conflicts with communities are disregarded and continue with impunity, they told Mongabay.

This is the context in which the mining company Alphamin Bisie, a subsidiary of the Canadian company Alphamin Resources and a South African government institution, the Industrial Development Corporation, decided to establish its mine and exploration activities.

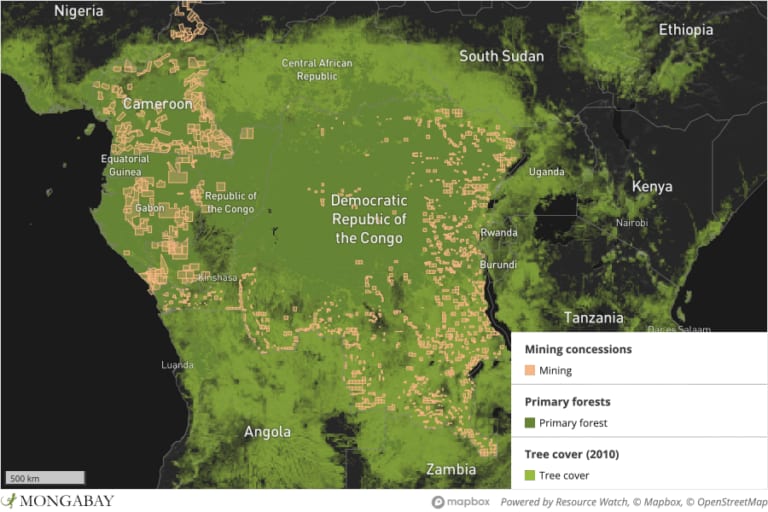

Mining concessions in the DRC are concentrated in the east, a region in active conflict.

Who consulted the communities?

In the lush forests of Walikale, Alphamin Bisie holds several mining permits, including two exploration permits to look for minerals (5270 and 10346), which are over 10 years old, and one mining permit to extract mineral deposits (13155).

Mongabay analyzed the coordinates of Alphamin Bisie’s mining permits in the territory and the maps of the community concessions based on geographic data. According to the data, the permits overlap with the community forests from the center to the south of Banamwesi and Motondo (10346) and to the southwest of Motondo (5270). According to a map by civil society organization, there is an overlapping area of about 2,000 hectares (4,942 acres) with the Banamewsi community forestry initiative (IFC) and 12,000 hectares (29,652 acres) with the Motondo CFCL. These forests — their customary lands — are the cornerstone of the communities’ agropastoral activities, hunting, and farming.

The perimeters of these two permits reduced over the years, we found, each time the permit was renewed (as required by the law). Still, the permits consistently overlapped with the forest concession initiatives and were close to the communities.

According to the communities, they were never consulted, nor did they ever give their consent to these activities, a legal necessity.

“At first, we didn’t understand at all. We had seen helicopters flying over our forests. Days later, our inhabitants mentioned seeing flags or other insignia in the forest,” a civil society representative, whose name is kept anonymous for safety reasons, told Mongabay over the phone.

Hubert Tshiswaka, the director of the Human Rights Research Institute (IRDH), said that according to the 2018 Mining Code, all companies are required to consult neighboring populations who would be affected by mining activities, even during the exploration phase. Here, “exploration” designates not only mineralogical exploration but also research on relevant environmental impacts that would need to be outlined in the scope statement, an agreement between the company and the affected communities. This duty to consult includes forest concession communities, such as in Motondo, who are involved in sustainable resource management.

Alphamin Bisie having received a mining permit means that the DRC Mining Cadastre, a technical body that oversees land and mining, granted the company permits without these communities being consulted.

“When we asked Alphamin officials, they denied having been in our forest,” the civil society representative said. According to the DRC Mining Cadastre Portal and a report written by an advisory group for the company, Alphamin Bisie is looking for tin, gold, copper, coltan, zinc, lead and silver in the forests.

Our research on the status of these permits and how they were acquired shows that very little information has been shared with the public. Very little is known by the neighboring communities themselves. What is disclosed instead unveils more questions or violations of the law.

According to the last published registry of active quarries in 2021, permit 10346 was valid until 2019 and needed to be renewed. According to a 2022 technical report prepared for Alphamin by the mining consultancy Bara Consulting, the same permit is set to expire on July 1, 2024. Legally, research permits in the DRC are renewed for a period of five years. This would indicate that the permit was again renewed without consulting the communities of Motondo and Banamwesi, in violation of the mining law.

In an email to Mongabay, John Robertson, the managing director of Alphamin Bisie, said that “a mitigation and rehabilitation plan dating back to 2012 did not identify the Banamwesi or Matondo as potential landowners.”

A village in Banamwesi. Image courtesy of a local source.

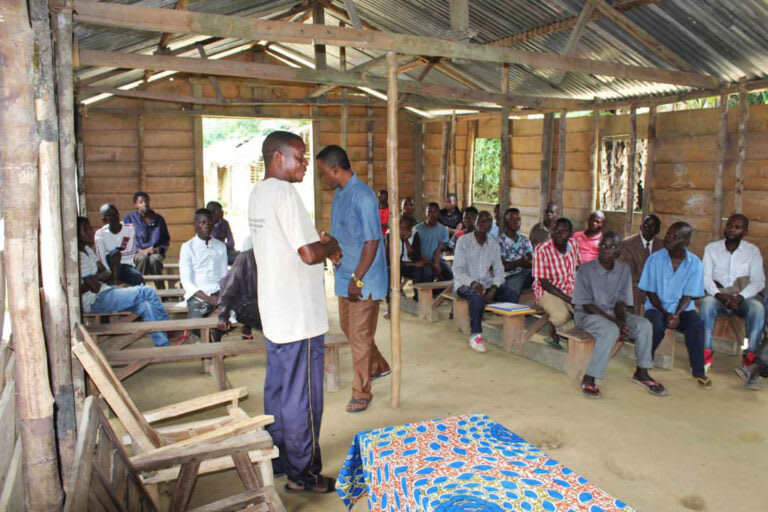

Community members from Banamwesi and Motondo discussing their issues with Alphamin Bisie mining company. Image courtesy of a local source.

The Banamwesi and Motondo communities are the Indigenous customary landowners and occupiers of the region, as recognized by law. They have been in active discussion with authorities in setting up community forestry concessions for the last seven years.

The situation with license 5270 is even more confusing. When asked about the status of the permit, Robertson simply said the permit was finally “abandoned in 2019.”

The publicly recorded dates of this exploration project contradict each other and the law. For example, according to an active quarries registry, permit 5270 was set to expire in 2018, while a technical report by Alphamin in 2017 indicates that it would be valid until May 23, 2023.

Based on the 2018 expiry date in the active quarries report and the law on renewal periods, the licence could have been extended by 5 years and granted until 2023, a date that aligns with that in their technical report. However, authorities did not answer our calls to confirm this timeline.

Our analysis and the silence from the DRC Mining Cadastre and authorities made it difficult to determine whether this permit is still officially active. When we looked at maps of the permit in their technical rapports and the Mining Cadaster Portal, it is clear that the perimeter of the permit reduced at some point between 2017 and 2022 — suggesting it would have been renewed during this period. If the permit was indeed renewed, this suggests another cycle of lack of consultation with the communities of Motondo and Banamwesi.

According to the civil rights representative, it doesn’t matter whether Alphamin really abandoned the site or not while they held a license. What matters, they said, is who gets the land.

“They say that they have now abandoned [that part of the land], but they have not returned that part to the owners, to the communities that customarily hold it. Now when they give up, that part goes back to whom? That’s what they need to address,” the representative told Mongabay.

The community monitoring team inspecting forests in Walikale. Image courtesy of a local source.

Confirming our analysis of the contradicting dates, a report by an NGO for women in mining, DYFEM, says that permit 5270 also had an official period of validity of seven years between 2011 and 2018, which is longer than the five-year period set forth by the law and regulations.

“The Mining Cadastre should clarify the reasons why […] permit 5270 received a longer period of validity,” the report said.

Alphamin Bisie did not answer our question on this issue.

Communities that don’t exist

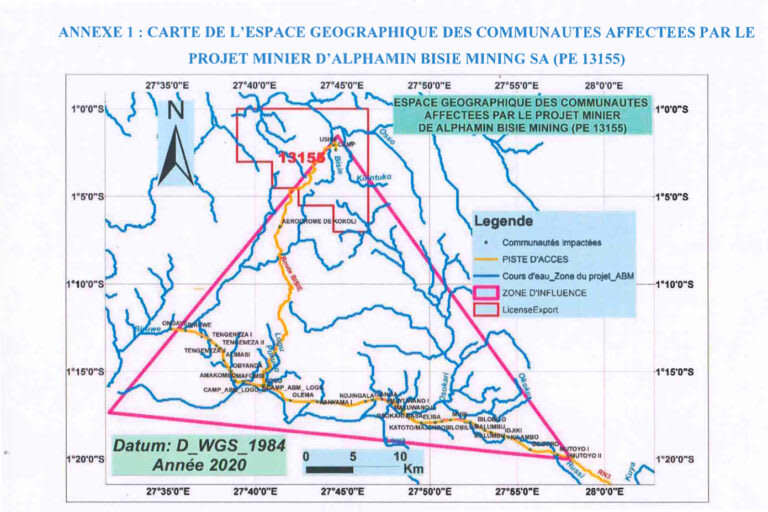

A similar situation is occurring at Alphamin’s active mine. Comparing the maps of the Banamwesi and Motondo community forest concessions and that of Alphamin Bisie, it is clear that that another permit, #13155 for the Bisie mine, obtained in 2015 and valid until 2045, is indeed close to the communities.

However, in Alphamin Bisie’s scope statement, which was signed by representatives from other local communities in 2021, Banamwesi and Motondo are not included. These two communities have complained about how close they are to the company and stated the need for consultation for almost a decade, but nothing has changed.

According to the Mining Code, miners are obligated to consult neighboring communities who could be affected by the company’s mining.

However, when it delineated the perimeter of its ‘zone of influence,’ the area in which communities may be affected by its mining, Alphamin looked toward communities established in the south of the zone, which are far from where its active mining site is located. Yet the Bisie mine is located less than one kilometer (0.62 mi) from the Montondo CFCL and is bout eight kilometers (five miles) from the Banamwesi IFC, two communities left out from the scope statement and its map. Alphamin’s technical reports also do not mention their presence.

According to managing director of Alphamin, these communities were excluded from the impact zone because they are not located downstream from the mine. Thus, they were not approved as a community potentially impacted by any pollution that could flow downriver.

Map in the scope statement of the mine’s ‘zone of influence,’ the area in which communities may be affected by its mining. Motondo and Banamwesi are located just to the left of the permit, but are not included. Screenshot of scope statement.

Community leaders and lawyers say the company still has an obligation to consultat over other potential environmental impacts, including social and economic impacts, because communities reside near the mine. But according to local leaders contacted by Mongabay, the permit was granted without the consent of the Banamwesi and Motondo communities. Officials in Banamwesi, for example, guarantee that they were not consulted. This lack of consultation was confirmed by the testimony of Chief Mbululu, the leader of the Banamwesi community.

The law requires that the community appoint a representative who has written authorization to speak on their behalf and scientific expertise on the issues that will be up for debate, said Jean-Claude Mpey, a lawyer who specializes in issues of the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities. However, the communities say this did not happen. Even if the community members were represented by their traditional chief, it would be illegal.

According to Abakofa Silabo Joachim, president of the NGO SODEP, which participated in Alphamin’s consultations with local communities for permit 13155, neither the Banamwesi or Motondo communities had representation during the consultations.

No source, whether the local authorities or Alphamin Bisie, has provided Mongabay with a written authorization attesting to the community’s decision, nor have they named an individual representing the two communities.

Fiston Misona, a former official from an NGO who worked with the local farmers in community forestry, said the administrative authorities of North Kivu knew of this violation of legal procedure from the start.

“[Those running Alphamin Bisie] took advantage of the community’s lack of awareness and the complicity of local political administrative authorities in Kinshasa,” Misona said, referring to the communities’ lack of knowledge of the law. However, no evidence was provided to support this accusation.

According to the 2022 technical report prepared by Bara Consulting, “The [mine] is remote in relation to the local communities, which reduces the potential impacts on the community.” The report only acknowledges the existence of the villages which are further “along National Road 3 (N3) between the town of Walikale and the mine.”

According to the technical reports, risks associated with the facility include the discharge of contaminated water and tailings from the facility into the groundwater or the environment as well as emissions of irritating and toxic gases. Image courtesy of a local source.

A technical report shows that there are other risks associated with the mine’s tailings storage facility that were not disclosed in detail to the neighboring communities of Banamwesi and Motondo. According to the technical reports, risks associated with the facility include the discharge of contaminated water and tailings from the facility into the groundwater or the environment as well as emissions of irritating and toxic gases. These issues could be the cause of diseases for people living nearby; environmental damage, including damage to farming land; loss of homes; and death, the report said.

However, the reports deny the magnitude of these risks because “there are no communities near the facility.”

Loss of land and no compensation

In 2017, a report by a civil society organization that advocates for transparency and better practices in mining, the OSCMP-RDC, said that relations between Alphamin Bisie and the surrounding communities would become strained if the company did not take their complaints into account. The 68-page document notes, for example, “the insufficient negotiations with the local community and the company’s insufficient involvement in local development.”

Since the mining company does not recognize the communities of Banamwesi and Motondo as affected by its mining, it does not owe them anything in terms of the development projects that it offers in other surrounding areas in accordance with the Congolese Mining Code.

According to the scope statement, the other communities, which are further away, will benefit from community development projects estimated at $4 million and which are divided between farming, fishing, livestock, energy, drinking water, health and education.

According to a community source, confirmation that Alphamin Bisie’s mining overlapped and was in close proximity to Banamwesi and Motondo came from Goma, the capital of the province of North Kivu, by chance in June 2023. By Decree no. 102 of March 16, 2021, the governor of North Kivu granted a local forest concession of 23,642 hectares (58,421 acres) to the community of Motondo rather than the 35,000 hectares (86,487 acres) requested. As for Banamwesi, the local land administration insisted that only around 13,000 hectares (32,124 acres) could be granted and that its maps needed to be reviewed, a forestry expert familiar with the case said. This review of the Banamwesi map before submission of the final file led to a loss of around 2,000 hectares (4,942 acres).

According to the source, the entity occupying the land not granted to either community “is none other than Alphamin Bisie” considering how close the latter is to the area refused in Motondo’s request.

A camp in Banamwesi forest for the community monitoring team. Image courtesy of a local source.

According to an alliance of local organizations focused on Indigenous peoples’ land rights, ANAPAC RDC, Alphamin Bisie took slightly over 2,000 hectares of land from the forest concession farmers, for whom the organization advocates. The two Indigenous communities in Walikale, North Kivu, are calling, in vain, for recognition of this and requesting compensation for their losses.

The silence of the authorities

In March 2024, both communities continued to call for discussions with the mining company’s management, to no avail.

But this is not the only obstacle in trying to hear from the other side. The government won’t respond either. Mongabay had the same experience: it was difficult to reach regional authorities. Such was the case with the official from Walikale, who offered to call his superiors in Goma. Upon doing so, the military governor, Constant Ndima, did not answer. His communications manager preferred “not to discuss such a subject over the phone” and never met with our envoy for an in-person meeting as requested.

Walikale, like the whole province of North Kivu as well as the neighboring province of Ituri to the north, has been under military administration since 2021. By declaration of a state of emergency, President Félix Tshisekedi, who wanted to put an end to the armed groups’ presence, appointed military officers as the administrative authorities of entities such as territories and provinces. According to members of civil society, military officials’ refusal to talk could be related to the fact that such problems are not their priority as they are not a regular civil government.

However, the same silence also persisted among the local mining and environmental administration, where several refused to comment on the case. Even among civil society organizations, some sources find the subject to be an embarrassment for the authorities and a sensitive one for them, and they require complete anonymity.

Moreover, the public administration has been criticized for its wait-and-see attitude. “The community forestry process is becoming burdensome. The administration acts as if the NGOs [who work with forest communities] are supposed to do everything,” an anonymous expert from a local NGO said. “However,” he added, “it is public officials’ job to support community forestry.”

A camp in Banamwesi forests for the community monitoring team. Image courtesy of a local source.

Are there any solutions?

In North Kivu, Alphamin Bisie’s reputation continues to be that it is supported by politicians and disregards claims and complaints against it by those claiming their rights. When Alphamin Bisie began mining operations, several hundred artisanal miners were phased out of the artisanal mining sites at Bisie and permanently left the site in February 2018. Nevertheless, the company is also credited with development projects benefiting the population: developing school infrastructure and agricultural projects in Wasa and the town of Walikale, the capital of the territory.

A mining company’s establishment for regulated mineral mining, as exists in several Congolese mining regions, can sometimes spark hope among communities to be able to access to certain goods when they are recognized as affected by the mining activities: Local residents often get access to drinking water, some even to paid jobs, while miners build schools, hospitals, and in some places, roads. These projects by natural resource and mining companies also contribute to making entire villages and regions viable.

But despite these projects, problems recur from time to time, as evidenced by provincial deputy Prince Kihangi Kyamwami’s report, shared by the local news site Ouragan. In 2022, the elected representative from Walikale noted that neither the mining or the royalties paid to the local administration by mining companies benefit either the population or the local administration itself.

In the same report, Deputy Kihangi said that the administration does not know “either the basis on which these royalties are calculated or the type of minerals that are exploited at the site.”

A report by ANAPAC in 2022 proposes restarting negotiations from scratch in order to involve especially the Indigenous Twa people of the Banamwesi and Motondo communities, who are not included in Alphamin Bisie’s scope statement.

Other impacts include the use of groundwater in the ore processing plant and the water treated according to environmental standards potentially being discharged into the area and watersheds. Image courtesy of a local source.

The report goes on to list the violations of these communities’ rights: the right to representation by appointed individuals; the right to free, prior and informed consent; non-compliance with the obligation to produce preliminary studies of socio-economic, environmental and health impacts; and violation of the right of free access to justice, land and natural resources, such as hunting or fishing rights.

Following multiple attempts to contact the company over the last year, the director of Alphamin finally got back to Mongabay after we contacted their consultation agency. Following our questions about the state of their permits and consultation with nearby communities, the director said he will ask the community development team to contact the representatives of Banamwesi and Motondo to “explain these matters.”

If this is done, it will be the first time the company has officially spoken with these communities, says the anonymous civil society representative. Representatives of the communities told Mongabay that they are awaiting this meeting.

Fiston Misona, the community leader of Walikale, said that it is also important for the public administration to involve itself and enforce national laws. He believes that it is in Alphamin’s interest to de-escalate the situation and find a platform for dialogue to settle these disputes.

“If there is no agreement between them,” he said, “even if the company has the means to get away with it, it will always be at a disadvantage.”

This article was also published here on Mongabay’s French site.

Banner image: A camp in Banamwesi forest for the community monitoring team. Image courtesy of a local source.

Related listening from Mongabay’s podcast: A just energy transition requires better governance & equity in the DRC, say activists

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay