By Justin Catanoso

In the nonstop battle to curtail illegal gold mining across the Amazon and the massive damage it does to rainforests, biodiversity and human health, a Brazilian research team has sharpened an economic valuation tool to help law enforcement more effectively prosecute companies buying illegal gold for sale in foreign markets.

The new research by the Conservation Strategy Fund (CSF) Brazil and published in January in the peer-reviewed journal Policy Resources is seen as bolstering the so-called Mining Impacts Calculator. The calculator was launched in Brazil in 2021 and adopted in Peru, Colombia and Ecuador in 2023. It was originally developed in partnership with Brazil’s Public Prosecutor’s Office not so much to pursue small-scale, illegal miners in the rainforest but rather purchasers of large quantities of illegal gold, with the aim of reducing demand for gold at its source.

“This current research is the first to present a unified methodology, as opposed to parts of the methodology that we published in previous studies,” Pedro Gasparinetti, a CSF environmental economist and lead author of the new study, told Mongabay. “The outcome is the improved accuracy of the estimations, especially of mercury contaminations” as it relates to human health, he said.

The study notes that the methodological improvements are “the first to combine” human health impacts with the valuation of environmental impacts such as deforestation and soil degradation.

Gustavo Geiser, a criminal investigator with the Federal Police of Brazil, has pursued environmental crimes in the Amazon since 2006. He told Mongabay the calculator “is extremely important” in bringing charges against gold buyers. “Considering that there are many variables and a very large number of areas to calculate values, the calculator allows us to estimate a value of the damage in all cases that go to court,” said Geiser, who provided technical support for the research.

The new research has improved the precision of cases being built for prosecution, he added.

Pedro Gasparinetti, an environmental economist, is director of the Conservation Strategy Fund-Brazil. Through his multiyear research on the environmental and public health impacts of illegal gold mining in the Brazilian Amazon, Gasparinetti has worked closely with Brazilian officials to refine the so-called Mining Impact Calculator to lend more statistical validity to criminal prosecutions against large-scale buyers of illegal gold. The calculator was adopted in 2023 in Colombia, Peru and Ecuador. Image courtesy of Pedro Gasparinetti.

Gasparinetti’s team put the cost of deforestation, land degradation and mercury contamination from illegal gold mining at $187,200-$389,200 per kilogram of gold extracted, or $84,900-$176,500 per pound. Most of this is attributable to health outcomes tied to mercury poisoning. Notably, those values are more than twice the market value of gold, the study found. They’re also more precise than when the calculator was originally deployed in 2021, Garparinetti said.

The new study emphasizes the importance of this greater precision. The authors write that the results can be used to compare “the private gains from the sales of gold” against “the social costs of 1 kg of gold extracted using mercury.” Ultimately, they note, “private profit is lower than the socioeconomic cost, which means that the exploitation of illegal mining results in a reduction of social wellbeing.”

“We now have a more stable function that relates the level of contamination in humans with the wellbeing impact on them. Previously, we only considered average impacts,” Gasparinetti said.

Mercury poisoning is connected to a range of neurological disorders, including tremors, memory loss, as well as cognitive and motor dysfunctions in adults. It’s especially harmful to the developing brains of young children.

The new study added new Amazonian regions to the methodology. In 2021, when the calculator was launched, CSF’s research was focused primarily on economic damage from illegal mining done in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory in Brazil’s Roraima state. Now, they assessed the situation in Brazil’s Tapajós Basin alone — the largest small-scale mining region in the world. The study estimated the socioeconomic costs generated by 4,547 hectares (11,236 acres) of small-scale alluvial mining at more than $1 billion in 2020. Illegal mining in the region has only expanded since.

“The novelty of this study is that it puts better numbers to the environmental, health and restoration costs that illegal mining does, using a real field-based case study,” Enrique Ortiz, senior program director with the Andes Amazon Fund, told Mongabay. “Although it may actually underestimate the total damage being done, it is a valuable advance that should serve well in lawsuits, fines and compensations cases.”

Small-scale illegal gold mining is widespread throughout much of the Peruvian Amazon, but especially in Madre de Dios, causing enormous harm to the environment and human population in what’s recognized as a biodiversity hotspot. The Peruvian government has been sporadic in its attempts to curtail illegal mining over the years. In 2023, Peru adopted the Mining Impacts Calculator for use by law enforcement and prosecutors to better fight illegal gold mining. Image by Enrique Ortiz.

Targeting buyers of illegal gold

The enhanced calculator comes as Brazil is increasing efforts to eradicate small-scale illegal gold mining on Indigenous lands and government-protected conservation areas. Given the vastness of the Brazilian Amazon — twice the size of India — and the thousands of far-flung illegal mining sites, the enforcement task is extraordinarily difficult. Although deforestation rates have dropped dramatically in the past year, 13% of the biome has already been lost to pastures, mining sites and crops. Plants, water, animals and people have been poisoned by mercury, an essential ingredient in pulling together flecks of gold from alluvial mining.

Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who took office in January 2023, pledged to expel more than 20,000 gold and tin miners from the Yanomami Indigenous Territory in northern Brazil, the country’s largest Indigenous tract with a population of 27,000. Hundreds of miners still resist and have returned, backed by a powerful local far-right culture and rhetoric of former president Jair Bolsonaro, who turned a blind eye to deforestation, illegal mining and Indigenous rights during his tenure (from 2019 to 2022).

Crackdowns on illegal mining are taking place elsewhere in the country, in states such as Pará and Roraima and in the Tapajós Basin.

There’s plenty of legal gold mining in the Brazilian Amazon, where miners are licensed to work in specific areas of the rainforest. The government owns all ore underground, and licensed miners can only sell to buyers authorized by the country’s central bank. Once processed into bars, legal gold is registered and taxes are paid. In cases of illegally mined gold, those charged and convicted are responsible for reimbursing the state both for the gold’s value and the environmental damage.

Gustavo Kenner Alcântara, a federal prosecutor in Brazil, told Mongabay the calculator is playing an increasingly important role in current prosecutions against three major financial institutions authorized to buy gold: Ourominas, FD’Gold and Carol. The companies stand accused of dumping more than 4,300 kg (about 9,500 lbs) of illegal gold on the domestic and international markets in 2019 and 2020. Fenix Metals and Parmetal face similar charges, said Geiser, the criminal investigator.

The cases are in court, and the companies could be held liable for hundreds of millions of dollars in damages if convicted, according to the calculator. Collectively, Gasparinetti said, Brazilian authorities are seeking more than $2 billion in damages, enough to cripple many buyers and potentially choke off some small-scale miners. The calculator has already contributed to cases that helped shutter some illegal mining operations.

“Our main target are those companies responsible for the finance and buying of illegal gold,” Kenner said, “but everyone that is in the gold’s illegal chain — exploiting, financing, buying or selling — could be responsible for damages. The calculator is important to improving our valuations and cases in court.”

Illegal miners in the Peruvian Amazon. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

Expanding use, but no panacea

The use of the calculator is spreading to law enforcement and courts throughout the Amazon. Colombia, Ecuador and Peru adopted it last year; Geiser said he’s in talks with the Peruvian National Police in Lima to exchange investigative strategies in building prosecutions. Bolivia and Suriname are now also considering adopting the calculator, as is French Guiana.

“We are moving in a direction of institutionalizing use of the calculator and its adoption as an online tool,” Gasparinetti said. “The minister of the environment in French Guiana is trying to determine, using the calculator, if the damage being done there from illegal mining is worth investing in law enforcement efforts to shut down operations and pursue prosecutions.”

Because of the environmental and human health devastation from mercury toxicity wherever gold mining is concentrated, Gasparinetti said the calculator can be used to estimate the investment it would take to shift away from mining techniques that use mercury. Governments could, where mining is legal, determine that it’s financially beneficial to subsidize a shift to mercury-free mining.

Meanwhile, he cautioned against too much optimism in fighting illegal gold mining and the damage it does to desperately needed, fully functioning ecosystems amid the climate crisis. Corruption is still rampant at all levels of Latin American governments, from town halls to state capitals, which can too often stymie investigations, on-site interventions and prosecutions, he said.

“We have so many problems with corruption, but again, we still need to tackle the problem,” Gasparinetti said. “We cannot simply give up and say it is simply too difficult to make the progress we need.”

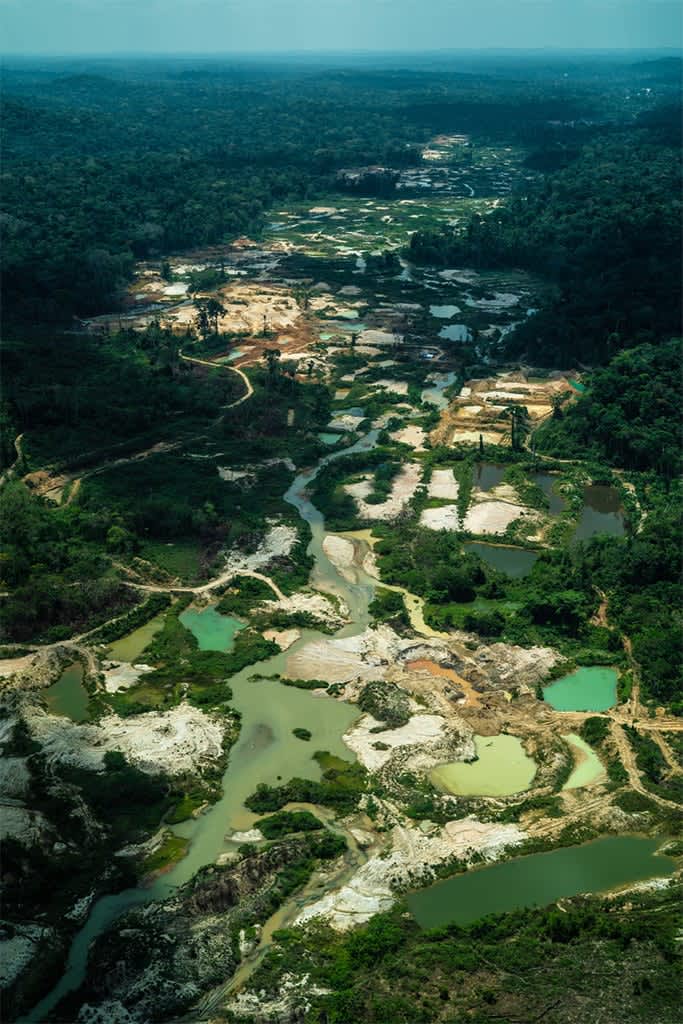

Gold mines in the Amazon, Brazil. Image by Fabio Nascimento.

Needed beyond prosecutions

Gina D’Amato is the executive director of the Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM), based in Colombia. Her organization works to formalize miners, or direct those who are willing to become licensed miners without mercury and sell only to state-approved buyers. She applauded the calculator’s growing adoption across the Amazon.

“We at ARM celebrate all these initiatives that are searching to stop environmental degradation, protect Indigenous land and local communities and improve awareness of the risk and consequences of illegal and irresponsible mining,” D’Amato told Mongabay. “This is indeed a step forward to understanding the complexity of the challenge of illegal mining from an economic perspective. This tool helps us all to bring back into the discussion the hidden economic actors that are pressing to continue with this activity in an illegal and irresponsible way.”

Deborah Goldemberg, a social development consultant formerly at WWF with expertise in the economics of illegal gold mining, has been following the development of the calculator since 2021.

“Miners are using it to assess their risk and make choices about whether it is worth it to mine illegally,” she told Mongabay. “Some realize the fines are larger than the value of their gold; others find the opposite and run the risk of being caught.”

Goldemberg said that under Lula, many Brazilians miners have moved back to legal areas and talk continuously about the fear of being bombarded or having their equipment confiscated. “Some say it is no longer worth working outside legal areas, even if there is more gold there,” she said.

Still, she noted, with gold prices at a near-record high of $2,145 per ounce in early March, illegal mining across the Amazon will remain worth the risk for countless small-scale miners. While law enforcement and prosecutions are necessary, Goldemberg said, governments need to do a better job establishing clear go/no-go areas for miners and a clear legal framework for them to follow and mine in appropriate areas. “This does not happen in many regions,” Goldemberg said.

Banner image: Small-scale illegal gold mining is widespread throughout much of the Peruvian Amazon, but especially in Madre de Dios, causing enormous harm to the environment and human population in what’s recognized as a biodiversity hotspot. In 2023, Peru adopted the Mining Impacts Calculator for use by law enforcement and prosecutors to better fight illegal gold mining. Image by Enrique Ortiz.

Justin Catanoso, a regular Mongabay contributor, is a professor of journalism at Wake Forest University in North Carolina in the United States.

Citation: Gasparinetti, P., Bakker, L. B., Queiroz, J. M., & Vilela, T. (2024). Economic valuation of artisanal small-scale gold mining impacts: A framework for value transfer application. Resources Policy, 88, 104259. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.104259

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay