A new study published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied reveals a stark racial bias in adults’ perceptions of pain experienced by children. This bias not only influences how adults judge the severity of children’s pain but also affects the kind of pain treatment they recommend, potentially leading to disparities in pain management for young Black children.

The investigation into these stereotypes stemmed from a recognition of the vital role adults play in recognizing and advocating for children’s pain management. Previous research has well-documented the existence of racial biases in the perception and treatment of pain among adults, showing that Black adults are often believed to be less sensitive to pain than White adults. This study aimed to explore whether such biases extend to perceptions of children’s pain, an area that had seen less scrutiny.

“National health surveys consistently highlight significant racial disparities in pain care, with Black individuals often receiving less comprehensive treatment compared to their White counterparts,” said study author Kevin M. Summers, a graduate student at the University of Denver and member of the Lloyd Social Detection Lab.

Previous research suggests that biases among perceivers may contribute to these discrepancies, with perceptions of Black individuals experiencing less pain leading to inadequate treatment. However, prior studies primarily focused on perceptions of adults’ pain. In our current investigation, we sought to explore whether these racialized beliefs about pain extend to judgments of children’s pain.”

“Understanding the influence of perceiver-level factors on the assessment of children’s pain is imperative for addressing disparities in pediatric pain management especially as young children frequently depend on adults for appropriate care and advocacy.”

The researchers conducted a series of eight experiments, focusing on the perceived pain sensitivity of Black and White children aged 4 to 6 years. The experiments engaged over 600 participants, mostly White adults, who were recruited through various channels, including university settings and online platforms.

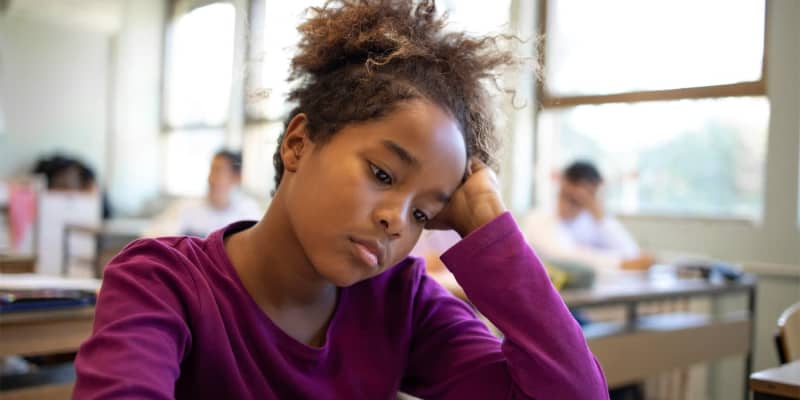

The core of these experiments involved images of children, both Black and White, displaying neutral facial expressions. These images were selected from the Child Affective Facial Expression (CAFE) set, ensuring that participants would not be influenced by the children’s emotional expressions. The children in these images were depicted in a way that controlled for age and gender, with specific experiments dedicated to examining perceptions of both male and female children.

The researchers found a consistent pattern across the various experiments: adults, primarily White, perceived Black children aged 4 to 6 years as less sensitive to pain compared to their White counterparts. This core finding was robust, emerging across multiple scenarios and assessments, and was remarkably consistent regardless of the child’s gender.

Perceived life hardship emerged as a mediating factor. Adults evaluated Black children as having experienced harder lives, and this perception was directly linked to beliefs about their pain sensitivity. Specifically, the harder a child’s life was presumed to be, the less sensitive to pain they were deemed to be. This suggests that underlying assumptions about the life experiences of Black versus White children significantly contribute to biased pain assessments.

The findings also shed light on the potential downstream consequences of these biases. When Black children were perceived as less sensitive to pain, they were also less likely to be recommended for intensive pain treatment compared to White children. This finding held across laypeople and, to a lesser extent, among elementary school teachers, suggesting that such biases might influence actual care and advocacy for children in pain.

“This study carries significant implications for the treatment of children across various contexts,” Summers told PsyPost. “In medical environments, perceptions of a child’s life hardship may influence assessments of their pain levels and consequently impact the type and amount of pain management they receive. Such dynamics likely contribute to the observed inequities in pediatric pain care.”

“However, these effects extend beyond medical settings. Parents, educators, and caregivers may inadvertently overlook or downplay the pain experienced by Black children, leading to inadequate care. For instance, teachers might overlook injuries on the playground, coaches may encourage Black children to push through pain, caregivers may fail to recognize or report discomfort experienced by Black children, and social workers may offer less comprehensive support to Black children who have endured abuse or neglect. Addressing these systemic biases is crucial for ensuring equitable treatment and care for all children.”

But the study, like all research, includes some limitations.

“While this study consistently reveals that Black children are perceived as less sensitive to pain compared to their White counterparts, our participant samples lacked diversity and medical expertise,” Summers noted. “Thus, further research is warranted to ascertain whether these racial biases in pain perception extend beyond our sample of primarily White, adult lay perceivers to a broader range of observers.”

“In particular, it’s unclear whether medical professionals harbor similar misconceptions regarding children’s pain; however, previous research indicates that biased beliefs about pain sensitivity and treatment may be prevalent among both lay individuals and medical practitioners.”

“Still, considering the significant role medical providers play in administering prescription pain medication, future investigations should directly explore whether pediatricians exhibit comparable biases in clinical settings,” Summers explained. “This endeavor is crucial for understanding and addressing disparities in pediatric pain management within healthcare contexts.”

“In our study, we observed that the perception of Black individuals as less sensitive to pain than White individuals extends to children as young as 4-6 years old. Our research team is currently delving deeper into whether these biased perceptions of pain sensitivity are also applied to other demographic groups, such as individuals with physical disabilities. Furthermore, we are investigating the accuracy of these beliefs.”

“Thus far, our findings suggest life hardship is not associated with an individual’s actual pain sensitivity, contradicting the common belief that adversity dulls one’s pain sensitivity,” Summers said. “This ongoing line of inquiry underscores the pervasive and potentially misguided nature of group-based pain stereotypes, emphasizing the critical need for further investigation in this domain.”

The study, “Racial Bias in Perceptions of Children’s Pain,” was authored by Kevin M. Summers, Shane Pitts, and E. Paige Lloyd. The research received the 2024 APS Albert Bandura Graduate Research Award for “the most outstanding graduate, empirical research paper.”