By Justin Catanoso

The bankruptcy filing in March by Maryland-based Enviva — the world’s largest maker of wood pellets from forest biomass — is rattling a European Union that relies heavily on biomass as a significant though contested renewable energy source.

The bankruptcy is also invigorating U.S. forest advocates determined to keep the Biden Administration from using new renewable energy credits to bail out the flailing company. On March 21, officials from five federal agencies visited North and South Carolina to see an Enviva pellet-making plant firsthand and hear environmental justice complaints over the impacts it is having on low-income communities.

But the company faces immediate threats to its ongoing viability that transcend its $2.6 billion debt and negative community impacts, according to a former maintenance manager at two Enviva pellet-making plants in North Carolina and Virgina between 2020 and 2022, and an exclusive Mongabay source.

As many as eight of Enviva’s 10 pellet mills in the U.S. Southeast, he said, are in such poor condition that they are producing fewer pellets monthly at a much higher cost due to intractable and costly maintenance issues.

“There’s no way Enviva is coming out of Chapter 11,” the former employee told Mongabay, referring to a court-ordered reorganization process by which the firm has a set time to restructure its debt and begin paying back creditors. “Their manufacturing equipment is not fit for the service it’s required to deliver. Only two of its 10 plants (one in Florida, one in Georgia, neither built by Enviva) are hitting their maximum achievable targets for pellet production.”

Wood chips piled in mounds more than 6 meters (20 feet) high cover the lot of the Enviva wood pellet plant in Ahoskie, North Carolina. Image by Justin Catanoso for Mongabay.

He added: “They also are not replacing equipment at the plants with the materials that will fix the problems. Plants keep going out of service for days at a time, and Enviva keeps spending millions to patch them up. Every ton of pellets they produce is at a loss. The more they produce, the more money they lose.”

These observations are reflected in Enviva’s public statements: In its March 13 bankruptcy filing, the company said it shipped 5 million metric tons of pellets overseas in 2023. That’s down from 6.2 million metric tons shipped in 2022, a 19.3% decrease at a time when demand for wood pellets in Europe and Asia was increasing.

Also, in its last quarterly filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission in November, Enviva wrote that $21.1 million of its $85.2 million in third quarter losses, or 25%, was attributed to “asset impairments,” which in accounting jargon means damaged equipment and machinery. This heavy expenditure on constant maintenance continues.

Carbon versus stainless steel

Interim CEO Glenn Nunziata is putting a bright face on the bankruptcy publicly: “We look forward to emerging from this process as a stronger company with a solid financial foundation,” he said recently.

But here’s the crux of the problem, yet unaddressed by Enviva: Most Enviva production facilities are built with carbon steel, which is less expensive (though less durable) than stainless steel, explained the former employee, who remains in close touch with plant management inside the company.

When it built its plants, Enviva planned to mostly use hardwood trees to make pellets. But when the price of hardwood rose sharply, the firm to control costs shifted to processing 80% pine and 20% hardwoods, instead of the opposite. But pine resins and added moisture quickly corroded and degraded the carbon steel equipment, especially in Southampton, Virginia, a plant Enviva said it has partially shuttered. Its four plants in North Carolina must also now close several times a year for maintenance, thus reducing annual production.

“Those plants need to be rebuilt with stainless steel, but that comes with a huge cost,” said the former employee, who declined to be named for reasons of family and professional privacy. “These plants are wearing down at an alarming rate. And the more pine they push through, the faster it wears. Maintenance costs keep piling up.”

Enviva has been counting on two enormous new plants in the Deep South to counter the lag in pellet production. But Nunziata said the company cannot afford to continue building in Bond, Mississippi, though it intends to restart construction in Epes, Alabama.

Enviva did not respond to requests for comment on its bankruptcy or the condition of its manufacturing facilities.

Felled hardwood and pine cut from a dense forest and piled high on a 52-acre lot in Edenton, North Carolina. The trees were later ground into wood chips, loaded into trucks and moved to the Enviva pellet plant in Ahoskie, North Carolina. Enviva had planned to use mostly hardwoods to supply its Southeast U.S. pellet mills, but company insiders say the current mix is 80% pine and 20% hardwood, with pine resin and moisture damaging facility machinery. Image courtesy of the Dogwood Alliance.

Battling for and against US tax breaks

Enviva’s collapse has been fast and profound. In April 2022, the public company’s share price peaked at $87 a share; the firm then was valued at $3.5 billion.

After a disastrous 2023, in which revenue plunged and losses totaled hundreds of millions, Enviva’s stock price tanked again and again. It is now trading at under 50 cents a share and the company is valued at just $34 million. As a direct result, a class action investor lawsuit against Enviva is advancing in Maryland district court.

Forest advocates are feeling vindicated: “Years of deceiving customers, destroying forests and polluting communities has finally caught up to Enviva,” said Danna Smith, executive director of Dogwood Alliance, a North Carolina-based NGO. “In the process, millions of taxpayer dollars have been wasted. Our government must not give one more dime to this failing, dirty industry.”

But that potential exists. Under President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), billions in tax credits and subsidies are available to producers of clean energy, like wind and solar energy companies. Millions are also available for forest industry innovations.

Tractor-trailers each loaded with 40 tons of wood chips waiting at Enviva’s pellet mill in Ahoskie, North Carolina, which opened in 2011. “There’s no way Enviva is coming out of Chapter 11, [bankruptcy]” a former Enviva employee and whistleblower told Mongabay. “Their manufacturing equipment is not fit for the service it’s required to deliver. Only two of its 10 plants (one in Florida, one in Georgia, neither built by Enviva) are hitting their maximum achievable targets for pellet production.” Image courtesy of Bobby Amoroso.

Biomass industry groups, on behalf of Enviva and other domestic pellet makers, are now actively pushing the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and other federal agencies to recognize wood pellets as a renewable energy source largely because trees can be regrown.

Wood pellets enjoy that renewable-energy designation in the EU and United Kingdom, which provide billions in subsidies for pellets which are claimed to produce zero carbon emissions. However, a host of scientific studies offer convincing evidence that burning forest biomass is not a climate solution, and produces rather than reduces heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions. Studies show that wood pellets actually emit more carbon dioxide per unit of energy than burning coal.

According to environmental groups, Enviva is seeking subsidies under the IRA from the Department of Energy and Treasury Department to help pay for its new plant in Alabama and restart construction in Mississippi — plants with the potential to each make 1 million tons of pellets annually, far more than existing plants.

U.S. Representative Alma Adams, a North Carolina Democrat, told Mongabay she does not want to see that happen.

U.S. Rep. Alma Adams, a North Carolina Democrat, was one of six members of Congress who wrote to the Biden administration in January arguing that extensive scientific evidence concludes that burning forest biomass for energy is not a legitimate climate solution, so should not qualify for renewable energy tax credits or subsidies. Image courtesy of the U.S. House of Representatives.

“Industrial wood pellet production pollutes communities where plants are located and contributes to deforestation in North Carolina’s prized woodlands,” Adams said. “That a giant corporation would need public money to maintain its solvency speaks to the make-or-break nature of public investments and incentives and underscores that public funding ought to go to proven climate solutions, not half-measures.”

Adams was among six members of Congress who wrote to Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm and Internal Revenue Service Commissioner Daniel Werfel in January emphasizing the science that discredits the climate-friendly claims of biomass energy advocates. The letter called for the rejection of all applications for industry tax credits.

Biomass, though, has plenty of congressional allies, especially in forested states such as Maine, Alaska and the Pacific Northwest. The EPA — which has long deflected pressure to designate biomass as renewable or climate friendly — is currently producing a study to determine the environmental and social impact of the wood pellet industry in the U.S.

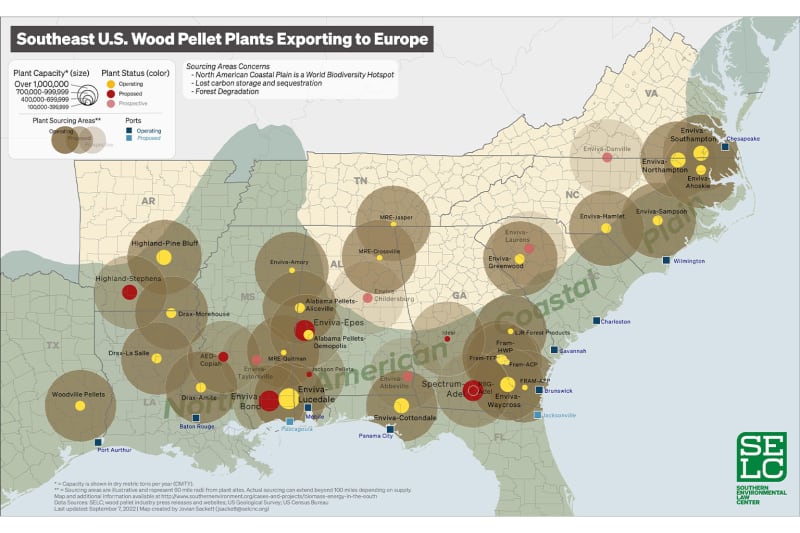

Map showing current and proposed wood pellet plants exporting to Europe. The woody biomass industry is exploding in size in the U.S. Southeast, but the Biden administration has so far remained silent on its policy toward the unregulated business. According to environmental groups, Enviva is seeking federal subsidies under Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to help pay for its new $375 million plant in Epes, Alabama and restart construction on its large facility near Bond, Mississippi. For a large scale printable version of this map, go here. Image courtesy of SELC.

Lobbying the Biden Administration

U.S. forest advocates now say that the possibility of IRA subsidies means they must open a new front in battling the biomass industry. For years, those advocates largely assisted their overseas counterparts in lobbying to change EU and UK bioenergy policy, though with little success.

“We know these new U.S. subsidies are appealing to the biomass industry,” said Adam Colette, a program manager with Dogwood Alliance. “As forest campaigners, we’re now telling officials in Washington, ‘Let’s not make the same mistake as Europe.”

To that end, Colette was among several environmental hosts to meet with Biden administration officials in North and South Carolina on March 21. Representatives from the EPA, the departments of Justice, Agriculture and Energy and the president’s Council on Environmental Quality toured an Enviva plant. Later, they met with leaders in local communities who have long argued that Enviva is contributing to public health harms through air pollution, clearcut logging and truck traffic.

“A goal of the visit was to show the impact the industry has on communities where they operate,” Colette said. “We commend the Biden administration for its support of environmental justice communities. These communities on the frontlines of industrial logging have suffered the consequences for too long. And if it’s not Enviva, its going to be someone else down the road.”

Nearly all Enviva plants are located in some of the poorest counties in the states in which they operate.

Imported wood pellets waiting to be burned at Drax, a former coal burning power plant converted to forest biomass in the UK; it is one of the world’s largest wood-burning energy facilities. Drax is also a major wood pellet producer, with manufacturing plants in the U.S. Southeast and British Columbia. It is currently pursuing plans for two new plants in central California. Image by DECCgovuk via VisualHunt (CC BY-ND).

Bankruptcy’s overseas impact; Drax lurking

Enviva’s bankruptcy is also being felt throughout the EU and UK, which receives the bulk of the company’s overseas exports. Officials there rely on burning biomass to claim alleged emission reductions against their Paris Agreement pledges; given a renewable energy designation, biomass smokestack emissions are not counted.

Burning wood currently makes up 60% of the EU’s renewable energy mix — though the emission cuts claimed for wood exist only on paper not in reality, say environmental analysts.

With Enviva’s dramatic drop in production, countries such as the Netherlands, Denmark and the United Kingdom, which depend heavily on Enviva pellets, are now facing uncertain supplies.

“This bankruptcy is very damaging to the entire biomass industry and the governments that depend on biomass,” Fenna Swart, a forest advocate with the Clean Air Committee in the Netherlands, told Mongabay. “If this changes the energy market, this is a huge problem across the EU. There appear to be few places to fill any [supply] gaps left by Enviva.”

EU forest advocates are renewing their lobbying of policymakers, urging them to turn away from wood pellets, but Swart confirmed that no nation has indicated any intention to do so.

Meanwhile, in yet another financial blow to Enviva, the company appears to have lost one of its biggest customers in Europe, RWE. The Germany-based energy company has long been an Enviva trading partner, importing some 2.5 million tons of pellets annually primarily underwritten by billions in subsidies from the Netherlands to be burned in Dutch facilities.

Because of unfulfilled contracts and the declining value of pellets on the open market, RWE has canceled its long-term agreements with Enviva and is demanding damages of more than $370 million. Enviva is reportedly refusing to pay.

Questions also abound now about UK-based Drax, which operates one of the world’s largest wood-burning facilities and which is also an expanding wood pellets producer. It has manufacturing plants in the U.S. Southeast and British Columbia, and is pursuing plans for two new plants in central California against growing opposition.

Drax is a major buyer of Enviva pellets for its energy plant in North Yorkshire, England. While Drax isn’t commenting, the company is organizing a U.S. headquarters in Texas. Forest advocates believe it, like Enviva, will seek U.S. tax support to underwrite its Deep South expansion.

With so much volatility in the biomass industry today, questions are mounting faster than answers. Can Enviva survive? Can Drax expand quickly enough in the U.S. to fill a potential 5-million-ton pellet gap and maintain UK subsidies? Will Russian wood pellets (banned due to its war with Ukraine), find their way back into the EU? Will the U.S. embrace biomass energy and subsidies like its overseas allies? And will the industry continue to grow, contributing significantly to climate change, or will it, like Enviva, implode?

“This bankruptcy reinforces the idea that there are no answers yet regarding the future viability of biomass for energy,” Swart said. “But it’s a great time to be asking these questions.”

Banner image: Wood pellets for biomass energy. Image courtesy of Dogwood Alliance.

Justin Catanoso, a regular contributor, is a professor of journalism at Wake Forest University in North Carolina.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay