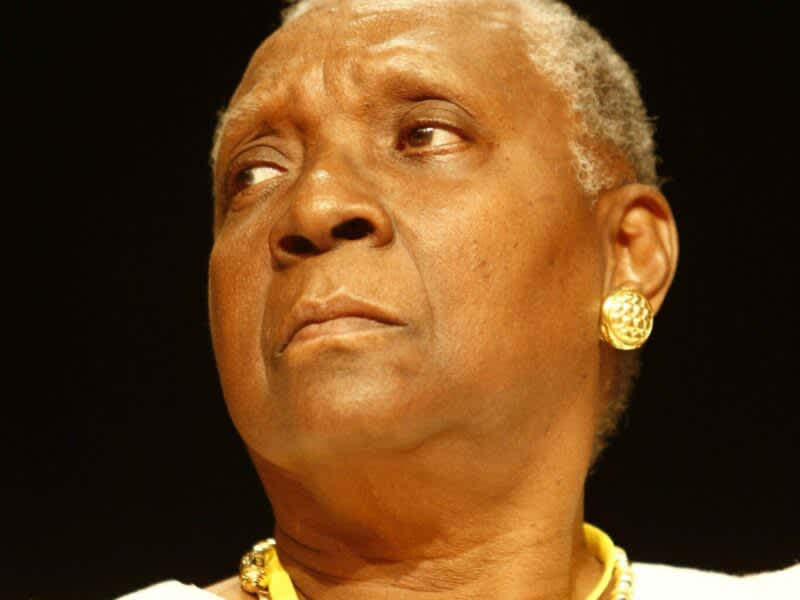

Guadeloupean author Maryse Condé. Photo by MEDEF on Flickr, (CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED).

Renowned Guadeloupean writer Maryse Condé, celebrated for her novels, plays and essays that delve into the multi-faceted and often nuanced layers of race, colonialism, gender, and cultural identity, passed away on the night of April 1 at a hospital outside Marseille, France. She was 90 years old.

Rest in power #MaryseCondé (here pictured by #HenryRoy in #RegardsNoirs)#RiP pic.twitter.com/tWGWRURujj

— Sarah Lawan (@SarahLawan) April 2, 2024

Laurant Laffont, her editor of many years, told The Associated Press that Condé had been suffering from a neurological illness that affected her vision to the point where she had to dictate her final novel, “The Gospel According to the New World.” Released in 2021 to critical acclaim for its skilful blending of Caribbean folklore with biblical events, it chronicles the journey of Pascal, a miracle baby on a quest for his purpose as the so-called child of God. The Financial Times interpreted the novel as “a parody of the New Testament; [an] odyssey through colonialism, religion and race.”

Richard Philcox, Condé's husband, translated the book into English in March 2023. Shortly thereafter, it was shortlisted for the 2023 International Booker Prize. At the time, Condé was the oldest author ever to have been nominated for the prestigious award, though she had been nominated once before, in 2015, for her entire body of work.

Condé was no stranger to literary accolades. Some of her most notable works include “Segu,” “I, Tituba: Black Witch of Salem,” and “Windward Heights” — a tribute to Emily Brontë’s “Wuthering Heights,” which Condé read as a child and credits with inspiring her to become a novelist. In “Windward Heights,” aptly set in Guadeloupe, where she was born in 1934, race and culture act as strong divisive forces. In 2018, she won the one-off New Academy prize in literature, an alternative to that year's scandal-plagued Nobel, though — to the chagrin of many — she was passed over for 2019's Nobel Prize in Literature despite her sharply insightful exploration of social issues.

Some of her many honours include Le Grand Prix Littéraire de la Femme (1986); the Liberatur Prize for Ségu (1988); a Lifetime Achievement Award from New York University's Africana Studies programme (1999); the French government's Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (2001); France’s Legion of Honour (2004) and the PEN Translates award for “Waiting for the Waters to Rise” (2020) and “The Gospel According to the New World” (2021).

Born Maryse Boucolon on February 11, 1937, in Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe, Condé emerged as a literary luminary whose writing bore witness to the legacy of slavery and colonialism in Africa and the Caribbean. Her work, which was influenced by anti-colonialist thinkers like Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire, transcended boundaries by challenging preconceived notions and shedding light on the complexities of Black identity.

Raised by a financially comfortable and well-educated family, Condé began writing at an early age and never really stopped. She reported for local newspapers in high school and later, as a student at the Sorbonne in Paris, publishing book reviews for its student magazine. While she remembers the effect that reading Joseph Zobel's 1950 novel “Black Shack Alley” had on her as a teen, opening her eyes to political activism, Condé's awareness of the lingering effects of colonialism also came through first-hand experiences of racism in France.

Years later, she would return to the Sorbonne as a faculty member. She also, at various stages in her career, enjoyed teaching stints at Columbia University, the University of Virginia, and UCLA in the United States. In 2005, then French President Jacques Chirac named her head of the French Committee for the Memory of Slavery.

Her unparalleled storytelling prowess, coupled with her unyielding dedication to amplifying marginalised voices, helped propel her to the forefront of the literary world, though her success came relatively late in life. Much of her youth was focused on raising her four children with Guinean actor Mamadou Condé, whom she divorced in 1981. Condé was nearly 40 when her first book, the controversial “Hérémakhonon,” which challenged the success of African socialism, was published. She later admitted that she “wasn’t prepared, either politically or socially […] to encounter Africa.” The success of “Segu,” perhaps her most famous novel, would come almost a decade later, and her impact only grew.

LITERATURE | Death at 90 of #MaryseCondé, major Guadeloupean writer of the 20th century. The author of “Ségou”, a remarkable piece of African literature, leaves behind an exceptional legacy made up of a wide selection of humanist works on colonialism, slavery and love. pic.twitter.com/lk1Z8rKWM8

— Nanana365 (@nanana365media) April 2, 2024

Naturally, social media users the world over shared their grief at the loss. Facebook user Scott Alves Barton hoped that Condé would “rest in [the] power, beauty [and] strength of [her] prose,” while Kavita Singh found every obituary “unsatisfactory”:

Maryse Condé was beyond description. She has no peer. I mourn for all of us and for all the stories she would have wanted to share, yet. Because she always had so much to give, as a writer, as a friend, as a mentor, as a model for how to be a woman without fear, despite all the pain of being a Black woman, and creating all the beauty we need to feel less alone.

The Booker Prize's Facebook page paid its respects to the “Grande Dame of Caribbean literature,” as did her publisher, World Editions:

Condé was without a doubt one of the greatest authors of our times. Her writing was modern, witty and intelligent, as well as being daring and full of life, and her dedication to her art was second to none. She knew how to blow life into each and every of her characters. World Editions was honored to have published her last three books, and she was greatly admired as an author and human being by our team.

The Haitian Times, meanwhile, honoured Condé for “her fearless exploration of colonialism, racism, and oppression,” and for igniting “global conversations on social justice, urging readers to confront societal inequities and aspire to a brighter tomorrow.”

Others remembered her brilliance, thanked her for teaching her readers how “to look at the world with unflinching eyes,” and acknowledged her “literary legacy connecting the Caribbean, Europe, and Africa.”

Claude Ribbe suggested that Condé's “rare” work has not yet been recognised — at least in France — in ways that are commensurate with “her immense talent,” and on x (formerly Twitter), Tasha Williams shared:

I learned French bc I wanted to read Condé and other francophone writers from the diaspora.#restinpower #MaryseConde https://t.co/7uHlKoWWmv

— Tasha Williams (@riseUPwoman) April 2, 2024

Fellow X user Natasha Lightfoot, unable to vocalise her grief, decided to let Condé have the last word:

“I don’t know how to do anything else but write. For me, writing is to be alive. When I stop writing, I stop living.” -the late great #MaryseConde https://t.co/nbzkWfWFCL

— Natasha Lightfoot (@njlightfoot) April 2, 2024

Through her writing, however, Condé's voice lives on.

Written by Janine Mendes-Franco

This post originally appeared on Global Voices.