By Liz Kimbrough

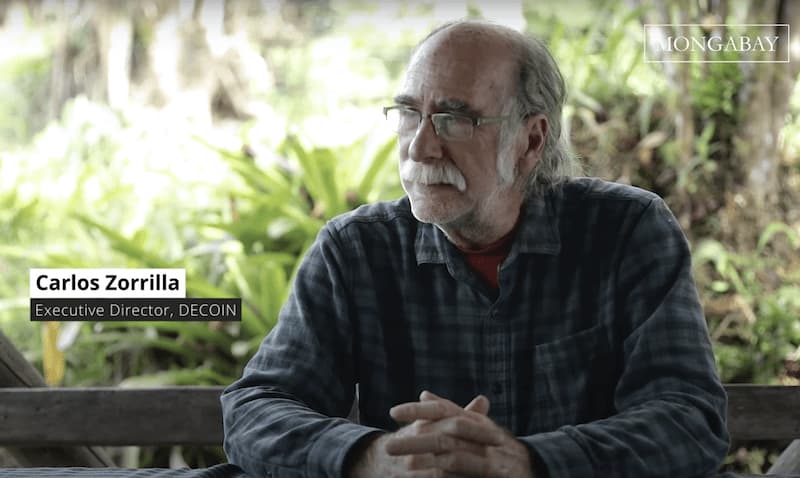

Carlos Zorrilla is a leader in what locals say is the longest continuous resistance movement against mining in Latin America.

Zorrilla’s family fled from Cuba to the U.S. in 1962 when he was 11 years old. He moved to the Intag Valley in Ecuador in the 1970s, citing his love for the cloud forest ecosystem there. Soon after he arrived, so did the first of the mining companies.

Over the following decades, Zorrilla and the organizations he co-founded, including DECOIN (Defensa y Conservación Ecológica de Intag), helped block five transnational mining companies and a national company from developing operations in one of the planet’s most biodiverse ecosystems.

In the process, Zorrilla and community members say they faced personal threats, smear campaigns, arrests and violence. But the movement also notched historic wins, including a constitutional case upholding the rights of nature against Chilean state-owned miner Codelco and the Ecuadorian national mining company in 2023.

Community members holding a sign that says, “let’s save Intag.” Communities in Intag Valley have been resisting mining for nearly 30 years. Photo by Carlos Zorrilla.

As a leader and public figure, Zorrilla is often sought out for advice by people facing similar threats. In response, he and two co-authors published Protecting Your Community From Mining and Other Extractive Operations: A Guide for Resistance in 2009 and an updated version in 2016. (The guide is also available in Spanish, French and Bahasa Indonesian).

“After getting rid of two mining companies, I was constantly being asked how the hell we did it,” Zorrilla tells Mongabay. “Rather than keep answering individuals, I wrote the manual. It’s much easier to just say, ‘Read the manual!'”

The 60-page guide shares experiences and resources, including the environmental and health risks of mines, strategies to prevent mining before it starts, key early warning signs a company is moving in, and advice on mitigating damage if a mine goes ahead.

Zorrilla says the most important point is to stop mining before it starts. To emphasize this point, he also published Elements for Protecting Your Community from Mining and Other Extractive Industries, which focuses on preventing mining from gaining a foothold.

“Stop the companies before they corrupt your communities and before they discover economically viable mineral deposits,” he says. “Once they start investing in exploratory activities it becomes progressively harder to get rid of them.”

Mining is a divisive issue within Indigenous and local communities. Some see economic benefits to address poverty, own their own mining projects, and highlight the need to negotiate better benefit-sharing agreements or collaborations with mining projects as a form of self-determination.

“But these memorandums only work with ethical mining companies and they are as rare as chicken teeth,” Zorrilla says.

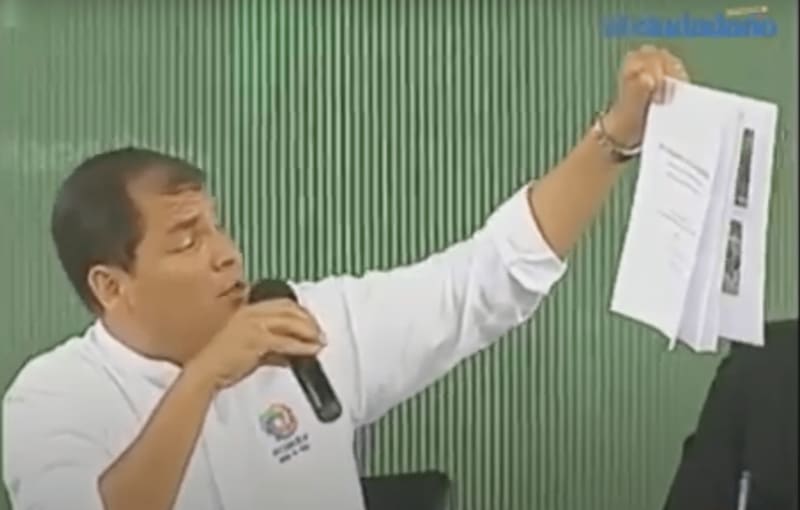

Zorrilla’s opinions on mining are contentious. After the publication of the resistance guide, Ecuador’s president at the time, Rafael Correa, denounced it on public television as “destabilizing” and a foreign-led interference, in a move that Zorrilla says was “great publicity for the manual.”

Former Ecuadorian President, Rafael Correa, holds up Zorrilla’s resistance guide on public television in 2009, denouncing it as “destabilizing”.

As the world transitions away from fossil fuels, the demand for critical minerals to feed “clean” energy technologies such as electric cars is rising. Thus, mining is also increasing.

However, many experts say mining in Ecuador, especially in the Intag Valley, is just a bad idea. Aside from the earthquakes, rainfall, steep slopes and lack of infrastructure, it’s a country with a wealth of other options for development, such as ecotourism potential or sustainable agriculture.

“It’s really a poor choice to develop large-scale mining in such a rich country,” says William Sacher, professor and researcher at Simón Bolívar Andean University in Quito, who studies large-scale mining and its impacts. “If you actually do the math just in terms of cost and benefit, if you take into account the costs of large-scale mining, they outweigh the benefits.”

Zorrilla’s work with DECOIN resisting mining as well as restoring forests and watersheds has been internationally recognized with awards, including the United Nations Development Programme’s Equator Prize in 2017. This year, Zorrilla won the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature’s award for defending nature’s rights.

It’s his connection to nature, he says, that keeps him motivated. “It is hard to put into words the connection I feel with the land and people, with the biological community I am part of,” he says. “What else could someone do that feels to be an integral part of a community? How could one not defend it against forces that would destroy it?”

In an interview with Mongabay’s Liz Kimbrough, Zorrilla discusses the guide and his experiences.

Mongabay: What inspired you to write this guide?

Carlos Zorrilla: I think two main reasons motivated me to write the guide. The first and most important was that we had gone through a lot in confronting a Japanese and a Canadian mining company in the 1990s and the early 2000s and had to do so without any idea of how to go about it. I kept wishing there was some concrete information on the best ways for communities to confront the presence of these companies. Much as I looked around, I was unable to find anything.

I thought other communities could benefit from our experience in successfully standing up to two transnational mining corporations and blocking mining development in our area (as of early 2024, civil society in Intag has been able to block five transnational mining companies and a national one from opening a mine).

The second reason is much more practical. After getting rid of two mining companies, I was constantly being asked how the hell we did it. Rather than keep answering individuals, I wrote the manual. It’s much easier to just say, “Read the manual!”

Mongabay: You mention that preventing a project in the exploration phase is much easier than stopping it once mining has started. What are some early warning signs that communities should look out for?

Carlos Zorrilla: First, it helps to clarify why it’s so much more difficult to stop a mine once it has opened. A large mining company can incur hundreds of millions of dollars in exploration costs — costs that, in most cases, the country issuing the licenses could be held liable for if the mining company is unable to develop the mining site. This is a result of a country signing bilateral investment treaties with other countries to protect the investments of private companies.

So, in essence, the more a company invests in a project, the more expensive it is for a signatory country to pay off the mining company to go home.

The other reason is that the longer a mining company is a territory, the more likely they are to learn how to co-opt people and institutions, and they waste no time doing so. It’s similar to contracting cancer or other similar diseases: you’ve got to treat its soon as possible, otherwise it becomes deadly or ravages your body so badly that it becomes unable to defend itself.

Another reason it is imperative to stop a company in its initial stage or before is that the longer a mining company explores, the greater the possibility of finding an economically viable ore deposit. If they are successful, companies are much more likely to convince governments to allow all permits and look the other way in cases of illegal activities. It is also much easier for the company to find investors if they can show they have a viable mine to develop.

An open pit copper mine in DRC. Image by Fairphone (CC BY S.A. 2.0)

Mongabay: What are the first signs a company is interested in exploring territory?

Carlos Zorrilla: You may find strange people wandering around the community asking questions. Another is if you suddenly find that private individuals start to buy large tracts of land. Your community could be subjected to social and economic surveys carried out by a government agency under the guise of social or economic development or identifying health needs.

Keep in mind that it’s essential for the companies to find out as much as they can about the communities and the inhabitants they will be dealing with. This also goes for local government needs. For example, they may identify basic needs, such as the lack of basic health services, road and school infrastructure that needs repairing, lack of safe drinking water, etc. Once these needs are mapped out, they will offer the community and/or subnational governments financial help to address them. They often even offer to create so-called development groups or organizations, such as farming co-ops or women’s groups, and provide initial funding to address some of the needs. Companies may sign financial agreements with local or state governments to help cover the costs of supplying communities with basic necessities.

Needless to say, the funding always has strings attached to it, the least of which is that the subnational governments and community groups support the mining company’s presence and, later, the development of the mine.

The most important thing to remember is that the main objective of the companies is to create complete dependency on what they provide, whether it is jobs, road maintenance, drinking water, or basic health services. The inhabitants become so accustomed to having the services provided by the companies that they forget that they have lived without these things all their lives or that it is the state or national government’s responsibility to provide them. The dependency can become so instituted that the locals stop petitioning the local or national governments to provide the services and rely solely on the companies. This can also apply to subnational governments, especially when the national governments purposely reduce their funding as a strategy for the mining projects to gain support from the local populace.

At the same time, the companies are gathering basic information about the community, they are also identifying key players within the community. These are persons who have influence or could be groomed to hold a position of authority. They are the first ones co-opted. It could be someone successful in business or a well-respected community leader. They, in turn, will do a lot of the work for the company, such as convincing their neighbors that mining is the best way for the community and families to get out of poverty. Or it’s really silly not to accept the company’s support to build that road everyone always wanted. That propaganda is infinitely more effective when espoused by individuals you know and respect.

Community members in Intag protest mining in the forest. Image courtesy of Carlos Zorrilla.

Mongabay: What do you believe are some of the best ways to stop a mine before it starts?

Carlos Zorrilla: The best way to know what you’re up against is to find out all that you can about the company: things like who the owners are, the company’s history, main sources of funding, and where the company’s stocks are traded (if it is a publicly traded company).

Once you know all that you can about the company, your main objective is to stop it before it starts gathering information, hiring community members, or buying land — certainly before it holds meetings in your community.

As soon as you suspect a company is interested in your territory, hold public meetings or assemblies where, hopefully, most of the community’s adult population can participate in deciding whether to meet with the company. It can help to invite knowledgeable people to discuss some of the problems the community will have to face if they open the door to mining.

It is absolutely essential that no one accepts meetings with company officials or government employees promoting mining development unless it’s in a public setting with everyone from the community invited.

It is strongly recommended that the bylaws of the community include provisions for any approval of activities affecting the natural environment or social peace of the community be approved by two-thirds majority of the community members. It is dangerous to let the board members of the community (president, vice president, secretary, etc.) represent the community when it comes to allowing activities that could have such terrible and long-lasting social and environmental impacts.

Mongabay: The guide says mining companies use many tactics to divide communities and quell opposition. What’s the most difficult company tactic to counter that you’ve encountered? What should communities be aware of?

Carlos Zorrilla: The companies can use multiple tactics to neutralize the opposition. We’ve experienced just about all. Anywhere from making up criminal lawsuits to try to imprison effective opposition leaders and hiring paramilitaries to violently access the mining site, to death threats, outright buying community leaders, to terrible smear campaigns aimed at discrediting resistance leaders and/or the organizations that support the communities.

Then there are soft tactics. One of the hardest to counter is the easy money that the companies offer to the leaders and, eventually, community members when they start working for the company. This is especially effective in areas where making a living off the land is difficult.

Needless to say, this will lure people away from the fields and the normally hard work that is agriculture. Remember, the company offers steady paychecks, often accompanied by social security and health coverage. One of the things we must do is point out that these jobs will not last more than a few years or until the mine opens. Only qualified personnel are required once a mine opens, with few exceptions. But the company will never admit to it.

Communities have to know what the sacrifices are of accepting the jobs the companies offer. These include very often permanent, ongoing social conflicts; it could also lead to the relocation of whole communities to make room for the mine and its infrastructure, possibly contamination of water sources, desecrating sacred lands, and direct impacts on sustainable activities like ecotourism or agroecological farming.

It’s also been documented that there is more delinquency and violence surrounding mining projects, among many other negative impacts. The impacts are especially hard on women. Most mining jobs go to men, worsening economic inequality within households. Women often have to replace men’s work in the fields, adding even more stress to their daily lives. There also tends to be more health problems from STDs, plus more interfamily violence in mining sites.

So, when mining companies come offering jobs, communities have to consider all the impacts, not just look at the positive aspects.

That is why it is so important not to let the company get this far. Communities have to know that mining companies and government officials lie when it comes to convincing communities about mining. That is one of the most important messages. They have to lie because if they were to tell the truth about the social and environmental impacts of mining, not a single person in the community would support them.

In this light, it’s important to invite knowledgeable persons and community members from other communities that have suffered at the hands of mining companies to share with the communities what really goes on when mining companies roll into your community.

Intag community members block security guards hired by the mining company Copper Mesa Corporation from entering Junin Reserve in 2006. Photo by Elisabeth Weydt.

Mongabay: You stress the importance of nonviolent resistance, even in the face of company intimidation and violence. Why is maintaining nonviolence so critical?

Carlos Zorrilla: In most cases, the transnational mining companies have much more money than the affected communities, and the companies are usually fully supported by state institutions, such as the police, military, intelligence units and often even the legislative branch. And if there is no separation of powers, also the judicial branch of government could add to the disparity. Thus, you can end up standing up to a huge repressive mechanism, especially if corruption is endemic in your country. Officials will try to ensure these mining projects succeed in countries where extractivism represents a significant part of their state funds. That means sending police or military to quash resistance movements if they see the opposition is jeopardizing the mining project.

Corruption plays a major role in the outcome of these projects too. It is very often the case that the more dependent countries are on nonrenewable resources to fill their coffers, the more corrupt they are. This means the state might be willing to criminalize the protest if they think it threatens these projects. The attorney general or equivalent could charge dozens of individuals with criminal or civil crimes, such as terrorism or sabotage, to intimidate the rest of the population. And it only takes a few of them to go to jail for that strategy to work. If you keep your resistance nonviolent, that scenario is much less likely to happen.

Having said that, I know it is very difficult for people to put up with so much injustice and not react violently. But a human rights defender once told me, in these cases, it’s OK for your heart to be on fire, but your feet should be made of lead and slow to move.

It is also a well-established strategy for the government or companies to provoke violent reactions from communities, which gives the government a pretext to militarize the mining site and arrest key leaders of the resistance.

Public perception is also important: you’re much more likely to get support from the rest of the country if they see your struggle as following the tradition of nonviolence. You will have a much harder time getting that support if your struggle is seen as violent.

One way to keep your struggle nonviolent is to rely on the judicial system, but that depends if you live in a country with a strong tradition of separation of power and fairly equal branches of government. Many mining projects have been stopped at the courts. However, it is also true that it is a very unequal playing field, given that the companies have millions of dollars to hire the best lawyers in the country, and communities often rely on pro-bono legal help. But it is possible to win despite such a grotesque asymmetry of power.

Gold mining on the Huaypetue River in Peru. Credit: Rhett A. Butler.

Mongabay: What resources or skills do you think community organizers who are against a mining project most need to develop further? Where can they turn for help?

Carlos Zorrilla: I think it would help community organizers improve their research capabilities. That includes learning as much as possible about a company and its investors, identifying possible allies within and outside the country, and learning what has worked and what has not worked in other struggles similar to theirs. Also helpful is for them to master social media to get the word out as far and as wide as possible.

Organizers must understand that struggles cannot be won if they remain local. They must seek support from the rest of the country and national and international human rights and environmental organizations.

It is also important to know that if a company is from overseas, there is a possibility that you can establish a rapport with NGOs in that specific country to help expose what the companies are doing in your backyard and possibly get financial support for your work. That is much more likely to work if the companies trade their stocks in well-regarded stock exchanges. Companies are afraid of a bad reputation, and such news that can affect their investment profile. So, reach out to as many other organizations as you can. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International are good ones, but there are others. Check to see which ones are operating in your country and keep them abreast of what’s going on.

If the mining site is in an especially biodiverse place with many threatened species, you should contact national and international environmental organizations, for example. It’s important to identify these organizations to pressure the government and companies to respect human rights, sacred lands and biodiverse places.

Establishing contact with the press is also important. Remember, most companies are afraid of bad publicity. In that light, it should be a mandate to denounce all of the companies’ dirty tricks and illegalities and make them look bad before the public. That implies, among other things, carefully documenting all of the company’s irregular or illegal activities and those of government regulators.

I’m leaving out the option of going to the legislative branch of government. Because of my experience, they very often side with the executive branch and the companies. But your country may have a more independent legislative branch you can appeal to. That means getting in touch with your local legislative representative and inviting them out to your community so they can see firsthand what the company is doing. Get them interested in your struggle and denounce what the companies are doing or plan to do.

Activist under the Save Sangihe Island movement protest against the planned gold mining operation in Sangihe Island, North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Image courtesy of Save Sangihe Island.

Mongabay: For communities that cannot completely stop a mining project, what advice would you give them to mitigate the worst impacts and protect their rights as much as possible?

Carlos Zorrilla: Many factors go into mitigating the impacts of mining once a mine has opened and is fully operational.

One key is to closely study the mine’s enabling documents, such as the environmental impact statement, management plan and/or operating license, and use whatever method is available to verify whether they are complying with the measures to mitigate the mine’s impacts.

It is very likely you will need help in interpreting the hundreds or thousands of pages of technical data contained in these documents. Don’t despair! Try to get help from national organizations working on mining issues.

Document and denounce illegalities at home and abroad. If you find enough egregious instances of noncompliance, and depending on your country’s judicial system for fairness, you might want to take them to court to make the government force the company to address the violations or even ask for the courts to close down the mine.

Use the power of the media to shine a light on the mining operation and permanently expose rights violations locally, nationally and internationally.

Identify the main investors and ensure they are kept up to date with the negative social and environmental impacts their investments are funding. This includes informing the regulators of the stock exchanges the company may be listed on. You should count on help from NGOs in the country the mining companies are registered in for this.

Building on the above, you can try to send representatives to their companies’ annual stockholder’s meetings to expose negligence or any illegalities the company has committed or is committing. This can also be accomplished by allies in the country the company is from. It is usually enough for them to buy just a few stocks so they can participate in these meetings.

If the company is based in a country belonging to the OECD, and if you have strong support from an NGO in that country, you might want to file a formal complaint against the company’s conduct using the OECD’s Guideline for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct. This will not stop the mine, but it should increase the scrutiny the mine is under and might stop new investors from investing in the company.

If the company is not listed in a public stock exchange, you must rely more on the first two suggestions, but try harder to get the pertinent authorities to monitor and control the company’s activities. You can help accomplish this by setting up community monitoring groups made up of persons unrelated to the company or the government to monitor the company’s activities. This way, you can register violations and expose the company. It helps to integrate hydrologists, biologists and geologists into the group or be trained by them. Part of the monitoring should include periodically checking water quality to document contamination.

Depending on your country’s laws and your budget, hiring biologists to find new species or species in danger of extinction within the mining site may help strengthen arguments in the courts and in public opinion to stop mining development.

The idea is to put the company permanently in the court of public opinion and, at the same time, pressure government regulators by letting them know that the companies’ every step will be documented and exposed and that the whole world will be watching.

Carlos Zorilla and his dogs walk through the forest in Intag Valley, Ecuador. Photo by Romi Castagnino for Mongabay.

Mongabay: At times protecting a community doesn’t just mean resisting a mining project, but making sure a community can properly benefit from projects and is included in management to prevent ecological disasters that affect residents. How do negotiating benefit-sharing agreements, memorandums of understanding or collaborations with mining projects fit into this guide (or what do you have to say about that)?

Carlos Zorrilla: These memorandums only work with ethical mining companies. And they are as rare as chicken teeth. The only way to make them work even with these outfits is if the communities are playing on an equal playing field. It often happens that the company creates community monitors only to manipulate them and the results they produce. The companies make sure they are the only ones paying the wages.

Mongabay: What would you change or add to an updated version of the latest guide?

Carlos Zorrilla: In the new version, if there is another, I would emphasize measures to stop the companies before they corrupt communities.

Mongabay: What keeps you motivated after 30 years of activism and resistance?

Carlos Zorrilla: What keeps me motivated? It is hard to put into words the connection I feel with the land and people, with the biological community I am part of. It is a reflection on the state of things, really. What else could someone do that feels to be an integral part of a community? How could one not defend it against forces that would destroy it? I do not feel apart from nature, a blessing and a curse at the same time.

Banner image of Carlos Zorrilla in the DECOIN office in Apuela, Ecuador with Jesus Prado, one of the four litigants in the rights of nature case. Photo by Romi Castagnino for Mongabay.

Liz Kimbrough is a staff writer for Mongabay and holds a Ph.D. in ecology and evolutionary biology from Tulane University, where she studied the microbiomes of trees. View more of her reporting here.

This article was originally published on Mongabay