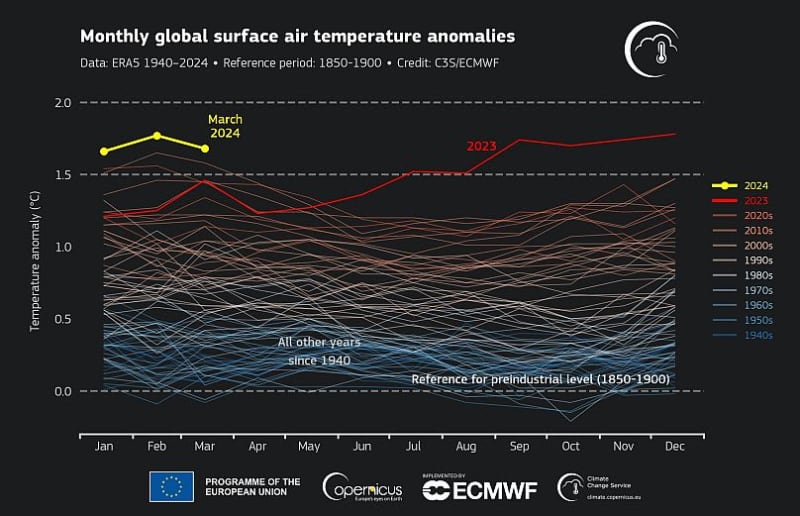

Last month was the hottest March on record, becoming the tenth record-breaking month in a row, scientists have said.

The global air temperature was 0.73°C above the 1991-2020 average for March, according to the EU’s climate service, and 0.10°C above the previous high set in March 2016.

It marks the tenth consecutive month where temperatures have been hotter than ever recorded for the respective time of year, after February also broke the old record by a tenth of a degree.

“March 2024 continues the sequence of climate records toppling for both air temperature and ocean surface temperatures,” says Samantha Burgess, deputy director of Copernicus Climate Service (C3S).

“The global average temperature is the highest on record, with the past 12 months being 1.58°C above pre-industrial levels.

"Stopping further warming requires rapid reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.’’

What is the ocean temperature record?

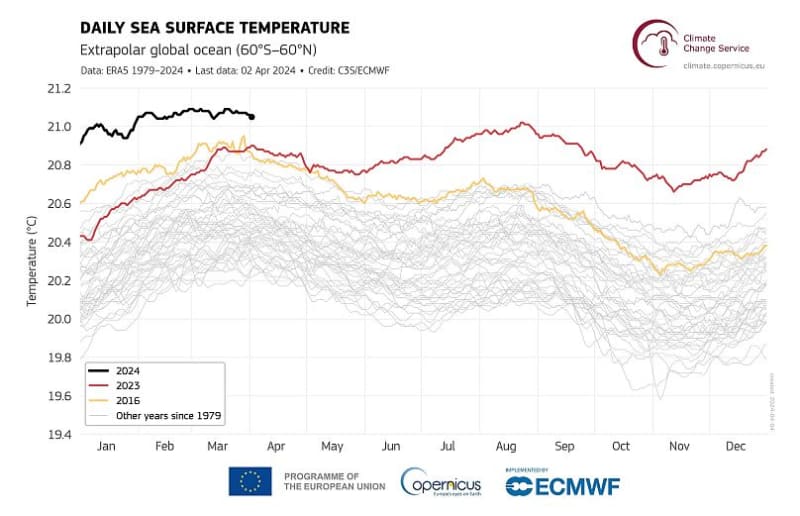

The world’s oceans are reflecting the unprecedented situation in the air.

Marine air temperatures remained at an unusually high level last month, despite El Niño weakening in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean.

As C3S director Carlo Buontempo told us previously, the El Niño phenomenon that began in June does not fully explain the unusually hot territory Earth has been in for the past 10 months.

“While El Niño adds and subtracts - depending on the phase you're in - from the global mean temperature, you have something that keeps adding,” he said. “And that's the greenhouse gases.”

Global sea surface temperature averaged out at 21.07°C in March: the highest monthly value on record. This reading for the oceans - which excludes the Earth’s polar ends - is marginally above the 21.06°C recorded for February.

Records are being tested in the icy polar oceans too. Antarctic sea ice ‘extent’ - defined as the total area of ocean that contains sea ice at concentrations above 15 per cent - was 20 per cent below average in March.

That’s the sixth lowest extent for March in the satellite data record, C3S says, continuing a series of large negative anomalies observed since 2017.

Was March a record-breaking month for Europe?

For Europe, last month was the second warmest March on record - only a tiny 0.02°C cooler than March 2014.

The average temperature on the continent was 2.12°C above the 1991-2020 average for March, with the greatest swing upwards in central and eastern regions.

Water wise, it was wetter than average in most of western Europe, as storms brought heavy rainfall over southern France and the Iberian Peninsula. Scandinavian regions were also wetter than average.

While the rest of Europe was largely drier than average, with particularly scarce rainfall over north-western Norway.

Critical 1.5C threshold breach creeps up

C3S uses billions of measurements from satellites, ships, aircrafts and weather stations around the world to inform its computer-generated analyses and findings, published on behalf of the European Commission.

Copernicus previously reported that in January 2024, global warming exceeded 1.5C for an entire year for the first time ever.

The 12-month average that hit 1.52C in January 2024 now stands at 1.58C for the past 12 months, as compared with the 1850-1900 pre-industrial average.

In the narrow window that remains to stop this temporary breach of a critical threshold becoming permanent, Dr Burgess’s straightforward message bears repeating: “Stopping further warming requires rapid reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.”