A recent study illuminates how a 400-year-old painting by Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens employs techniques that modern-day marketers could use to capture the attention of consumers. By examining eye movement patterns as participants viewed Rubens’ “The Fall of Man,” the research found that certain elements in the painting effectively guided viewers’ focus towards Eve, the central figure, more so than in the original version by Italian painter Titian.

The research has been published in the Journal of Vision.

The study was driven by a desire to understand the psychological underpinnings of visual perception and attention. By comparing Rubens’s work with that of his predecessor, Titian, who painted the original version of “The Fall of Man,” the team of researchers — led by Robert G. Alexander, Ph.D., assistant professor of psychology and counseling at New York Institute of Technology — sought to quantify the influence of specific artistic changes on viewers’ gaze patterns.

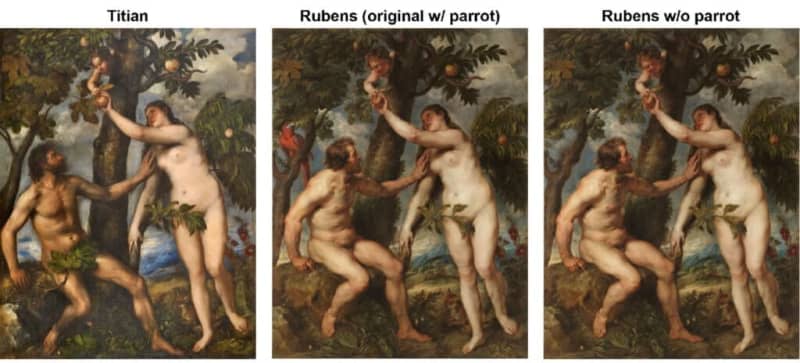

Titian’s original version, created in the 16th century, captures the moment of temptation in the Garden of Eden with a focus on the interaction between Adam, Eve, and the serpent, depicted with the upper body of a human infant. About a century later, Rubens recreated this scene with significant modifications that altered the narrative focus and visual impact. Unlike Titian, Rubens directed both Adam and the serpent’s gazes towards Eve, added a visually striking red parrot next to Adam, and adjusted Adam’s posture to lean towards Eve.

The research team conducted two experiments to investigate how specific artistic elements in Rubens’s and Titian’s versions of “The Fall of Man” influence viewer attention.

In the first experiment, the researchers sought to understand the overall impact of Rubens’s alterations to the original composition by Titian on viewers’ gaze distributions. Thirty-three participants were recruited to view digital copies of both paintings, as well as a modified version of Rubens’s painting from which the red parrot was digitally removed.

Participants were seated comfortably in front of a video monitor, resting their forehead and chin on a support to stabilize their head position, ensuring accurate eye movement tracking. Each participant engaged in a “free-viewing” task, where they were asked to view each image as if they were in an art gallery or museum, with each image presented for 45 seconds.

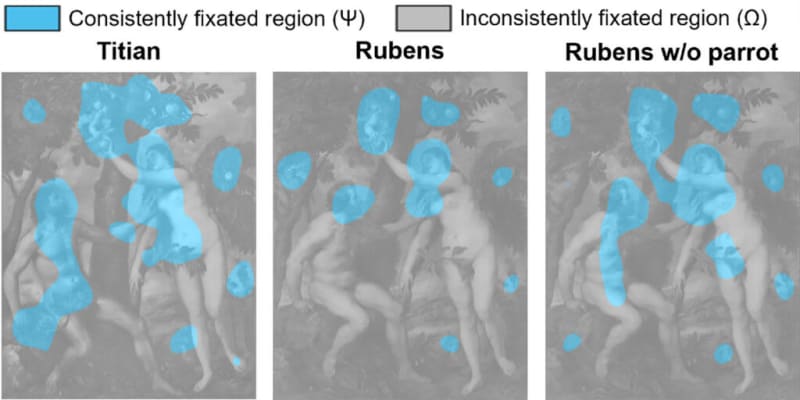

Eye movements were recorded using a video-based eye tracker, capturing where and how participants’ gazes moved across the artworks. The analysis focused on identifying regions within the paintings that consistently drew viewers’ attention, using heatmaps and scan paths to visualize gaze patterns.

The researchers found that participants’ gaze was more frequently and intensely focused on Eve’s face in Rubens’s painting compared to the broader distribution of attention in Titian’s original work. This indicates that Rubens’s alterations, particularly the redirection of Adam and the serpent’s gazes towards Eve, successfully concentrated viewers’ attention on Eve.

Furthermore, the analysis of eye movement patterns when the parrot was digitally removed from Rubens’s painting suggested that the parrot played a significant role in how attention was distributed across the painting.

Building on the findings from the first experiment, the second experiment delved deeper into the specific role of the parrot in Rubens’s painting and its effect on visual perception. Eighteen subjects participated in this phase, focusing specifically on the Rubens painting and the digitally altered version without the parrot.

The researchers employed a more specialized setup, placing a small red dot over one of Eve’s eyes in the image to serve as a fixation target. This detail encouraged participants to fixate on a specific point, allowing the team to assess how sustained attention on Eve’s face influenced the visibility of the parrot.

Participants reported their perception of the parrot’s visibility—whether it appeared to fade or intensify—throughout the trial. This experimental design aimed to explore the phenomenon of Troxler fading, where stationary objects in the visual periphery can fade from perception when one’s focus is maintained on a different fixed point.

When participants fixated on a point near Eve’s face, the parrot, despite its bright coloration, tended to fade from visual perception if it did not directly attract the viewer’s gaze. This effect was consistent with the hypothesis that Rubens might have used the parrot not just as a symbolic or decorative element but as a deliberate technique to manipulate the viewer’s visual attention and perhaps to enhance the narrative focus on Eve.

Additionally, the researchers uncovered that this perceptual fading was influenced by microsaccades, small involuntary eye movements that play a role in maintaining visual perception. Together, these findings underscore the power of artistic elements to shape viewer engagement and highlight the sophisticated understanding of visual perception that artists like Rubens may have possessed.

“While we may never know why Rubens wanted to direct attention towards Eve, our findings show that his critical deviations from Titian’s painting have a powerful effect on oculomotor behavior—techniques that today’s marketers and designers may find useful,” said Alexander. “From a psychological standpoint, it also goes to show you that how and where we focus our attention is not just determined by what we see, but also how others want us to see it.”

However, the research also faced limitations, such as the study’s sample size and the artificial setting of viewing digital reproductions rather than the original artworks. Future research could expand on these findings by exploring different art styles and periods or by employing more diverse and larger participant groups. Such studies could continue to unravel the complex interplay between artistic intent, viewer perception, and visual attention.

The study, “Why did Rubens add a parrot to Titian’s The Fall of Man? A pictorial manipulation of joint attention,” was authored by Robert G. Alexander, Ashwin Venkatakrishnan, Jordi Chanovas, Sophie Ferguson, Stephen L. Macknik, and Susana Martinez-Conde.