Illustration by Probox. Used with permission.

This article is part of the output of the “C-Informa” Information Coalition, a Venezuelan journalistic team that aims to confront disinformation and is made up of Medianálisis, Efecto Cocuyo, El Estímulo, Cazadores de Fake News and Probox, with the support of the Consortium to Support Independent Journalism in the Region (CAPIR) and the advice of Chequeado of Argentina and DataCrítica of Mexico. An edited version was published under a media agreement.

For years, the discourse of Chavismo on social media has expanded thanks to the work — paid for by the government of Nicolás Maduro— of citizens who help promote narratives in favor of his administration amid an ecosystem of propaganda and misinformation that is sustained by practices such as the closure of the media, persecution of the press, and communication influences.

The strategy of citizens and public workers promoting trends on social media is not new in Venezuela. In fact, these people are the ones who really maintain the volume of Chavismo's communication deployment in spaces like X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, and Facebook.

However, contrary to what the government makes us believe, this volume does not come mostly from the citizens’ conviction to praise the public policies of the Maduro government. Rather, it hides a very well-orchestrated communication strategy, perfected in recent years, that employs ordinary Venezuelans, who, in exchange for rewards such as payments (bonuses given out by the government to battle the economic crisis and reward political affiliation) or cell phones, follow specific guidelines to publish and replicate trends on social networks.

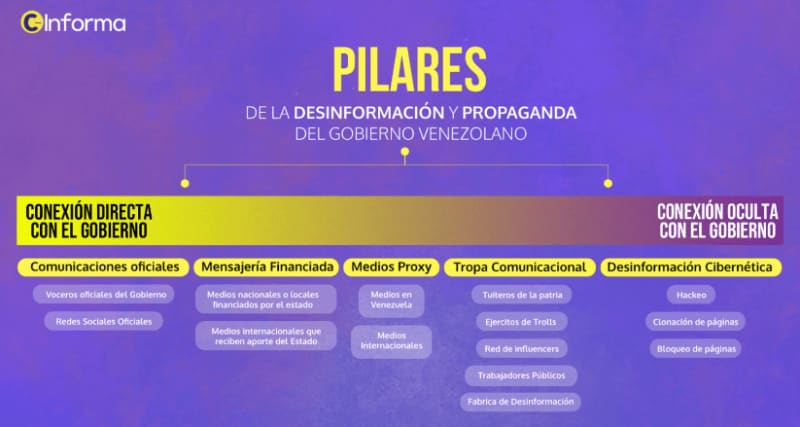

Text reads: At the top, pillars of the Venezuelan government's disinformation and propaganda. Next row: “direct connection to the government” at the left end of the scale and “hidden connection to the government” at the right. Next row, in yellow, From left to right: Official communications, financial messaging, proxy media, social media farms, digital disinformation. Infographic made by C-Informa. Used with permission.

A story behind hundreds of tweeters

Jesús, who asked for his identity to be hidden for security reasons, was promised an opportunity to get extra money at a time when his salary did not allow him to survive despite having worked for 15 years in education. Over the years, the economic crisis, hyperinflation, and frozen salaries have pulverized his salary, which is currently around USD 20 a month.

On the day of the meeting, Jesús was not alone. At least 10 other colleagues filled the small room where they were summoned in the state of Trujillo in western Venezuela.

“This is a training course for us to expand the communication of educational achievements in Venezuela,” they said. Two men introduced themselves in the room as the regional coordinators of the project.

Within minutes, Jesús understood that the idea was to regionally promote the messages of the Center for the Development of Educational Quality (CDCE), a government institution that operates at the national level. That's why Jesús was there. To join the group that, at the beginning of 2024, would be in charge of promoting narratives of the country's educational achievements on social networks, mainly X.

Promoting and showing educational achievements is in high contrast with the teacher protests in recent years in Venezuela, as these have reflected the discontent of workers in the sector due to poor salaries and lack of resources to work. Educational quality has also decreased, as studies have shown.

Read more: Teachers ignored: How the Venezuelan government overshadows the teacher’s protests with digital propaganda

In Venezuela, 11 million children are of school age, but only 6.5 million are enrolled in the educational system, while nearly 200,000 teachers left the classrooms to emigrate or find other professions. School dropouts go hand in hand with poor infrastructure (60 percent of public schools do not have basic services such as lighting, bathrooms, and internet), which partly explains why 80 percent of high school graduates fail exams testing basic mathematics skills, according to a study by the Andrés Bello Catholic University (UCAB).

These digital workers of Chavismo move like soldiers working to win a “communication war,” as different figures in the Maduro government have called it. To do so, they use a large amount of money, equipment, and talent whose sole objective is to promote propaganda and misinformation through social networks, one of the only ways that a large part of the Venezuelan population has to access information.

An article published by Cazadores de Fake News portrayed how a tweeter who works with more than 15 different X accounts earned around USD 80 a month for promoting the hashtags of the Venezuelan Ministry of Information. She worked for several months until everything changed when she no longer received reward bonuses.

It is no coincidence that the proposal to Jesús came at a time when the hashtags promoted by the Ministry of Communication and Information of Venezuela stopped gaining as much reach as before. Although “Twitterzuela” continues to be dominated by Chavismo in terms of volume in conversation and momentum of daily hashtags, a drastic drop in the momentum of Chavista propaganda was recorded after the arrival of Elon Musk.

The closure of free access to the API made it impossible to publish the hundreds of tweets that people made to promote hashtags, so the bonuses for being “active on social networks,” which were granted to the so-called Tweeters of the Homeland through the Homeland System, was paralyzed and, with that, so was the work.

Fewer payments, fewer tweets

The dynamic of positioning trends in Venezuela by the Ministry of Information (Mippci) has worked for years in the following way: Mippci displays a hashtag in the morning on its account on X and lists it as the hashtag of the day. After the publication of this tweet, the people who were part of the Tweeters of the Homeland, the communication troops, and public employees begin to write tweets with that hashtag to generate volume and position it as a trend.

In mid-2023, ProBox reported a digital protest by “Tweeters of the Homeland” because the government did not pay them the promised money. In the complaints, they asked for the payments that each person was entitled to for promoting the hashtag of the day as dictated by the Ministry of Communication and Information. In protest, they posted the hashtag #RespetoParaLosTuiteros (#RespectForTweeters), which got more than 10,000 tweets in one day.

During 2023, ProBox recorded 821 sociopolitical trends in the digital conversation on X, which concentrated more than 205 million tweets. Of all these, 95.25 percent were generated by Chavismo. However, the problem is not that Chavismo speaks more on X, but that much of this conversation is not real. This digital distortion can be measured by calculating the percentage of users who use their accounts as a bot or automated account would do. That is, they behave in an “inorganic” way.

At the threshold of a presidential election, in which social networks become relevant as one of the most important spaces for debate in the country, Chavismo's communication power to spread propaganda and disinformation has proven able to tip the balance and influence the agenda national public.

Written by ProBox Translated by Ameya Nagarajan · View original post [es]

This post originally appeared on Global Voices.