By Aimee Gabay

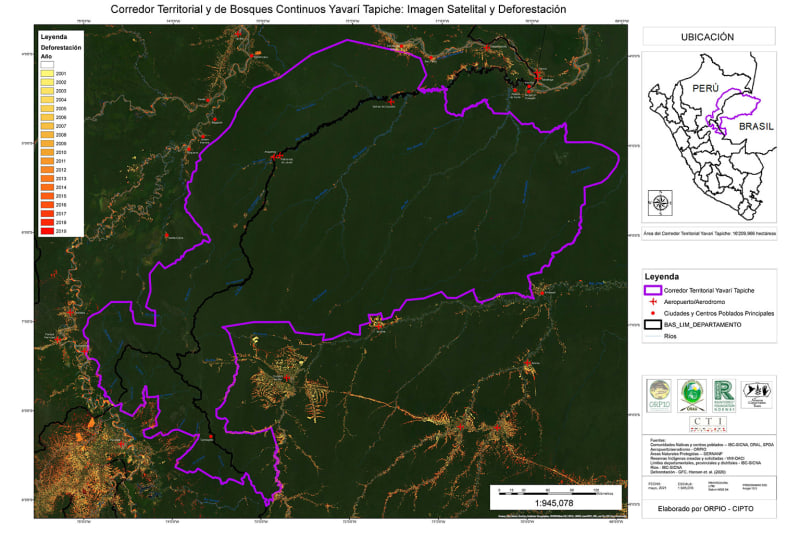

Indigenous organizations from Peru and Brazil are joining forces to push their respective governments to safeguard a 16-million-hectare (39.5-million-acre) territorial corridor in the Amazon that stretches from the Tapiche River in Peru to the Yavarí River in Brazil.

The 15 Indigenous organizations, which include the Indigenous Peoples of the Eastern Amazon (ORPIO) from Peru and the Union of Indigenous Peoples of the Javarí Valley from Brazil, plan to create a binational commission to define cross-border policies for the protection of peoples in isolation and initial contact (PIACI) who live inside the Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor and cross freely between both countries. The corridor spreads across the departments of Loreto and Ucayali in Peru and Amazonas and Acre in Brazil and is also home to the greatest diversity of primates in the world, including spider monkeys (Ateles belzebuth) and pygmy marmosets (Callithrix pygmaea).

“We proposed the creation of a binational commission made up of Indigenous organizations to strengthen the protection strategies of the PIACI, as well as to call for and demand urgent action from countries to stop the territorial invasions,” said Apu Miguel Manihuari Tamani, an Indigenous leader who forms part of ORPIO’s board of directors. “[There’s a] need to articulate efforts for the monitoring, management and surveillance of the territory between Indigenous organizations, both at the national and cross-border levels.”

This effort faces challenges from politicians in both countries who favor an agribusiness and development model that would scrap and restrict the recognition of Indigenous territories for plantations or industry.

The idea to set up a corridor in this location is not recent. The organizations have been pushing for the protection of this territorial corridor, and others, since 2011. Between 2016 and 2021, ORPIO led the studies to prove the existence of the Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor on the Peruvian side of the border, which was presented to Peru’s Ministry of Culture on Dec. 9, 2021.

A map of the Yavari-Tapiche Territorial Corridor. Image courtesy of ORPIO.

Because of slow progress on behalf of the state and an increase in threats to these territories, ORPIO drafted a new bill to push the Peruvian government to formally recognize the Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor and several others, such as the Yasuní-Napo-Tigre and Putumayo-Amazonas, and to grant the PIACI the protections they need. Still in its initial stages, the draft is currently being shared with other organizations in the region, with the aim of presenting a joint proposal to the Peruvian Congress and other sectors of the state responsible for PIACI protection in the coming months.

Beatriz Huertas, an anthropologist who specializes in the study of PIACI and territorial corridors, told Mongabay the corridors are home to possibly the highest concentration of isolated Indigenous peoples in the world. But illicit activities on both sides of the Brazil-Peru border, including the rapid expansion of coca leaf crops, illegal mining, deforestation and drug trafficking, mean people in isolation and initial contact are at risk.

“They are not like us who have our community, who have our little house; they are not, they are wanderers, just as we or our ancestors have once been,” said Apu Roberto Tafur Shupingahua, coordinator of the Platform of Indigenous Organizations for the Protection of the Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor at ORPIO.

“The problem is that the [Peruvian] state has abandoned the communities for many years, and if it were not for our organizations, nothing would reach these communities,” he said.

Peru’s Minister of Culture Leslie Urteaga told Mongabay she met with the Indigenous organizations on March 22 to discuss the proposals. When questioned about what actions she had taken to deal with the threats to the PIACI, she said the ministry had organized 757 patrols in 2023 to detect threats linked to possible illicit activities and, this year, it has carried out more than 200, in addition to nine monitoring operations.

Beatriz Huertas, an anthropologist who specializes in Indigenous Peoples in Isolation or Initial Contact, also known as PIACI. Image courtesy of ORPIO.

A technical team from ORPIO visits communities to socialize the Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor initiative. Image courtesy of ORPIO.

Working across created borders

The cross-border nature of this effort is rare, said Hilton da Silva Nascimento from the Brazilian Center for Indigenous Work (CTI).

“Everything is new, and we have to remember that this involves two different countries, two different histories, two different ways of doing policy and politics, alliances with Congress and the power forces of both countries.”

The goal is simply to defend “our PIACI brothers” wherever they go, Tamani explained. “They do not know about borders; they go from Peru to Brazil, and they do not know about those limits.”

By creating cross-border Indigenous policies, Nascimiento said it will allow the Indigenous organizations to form a more formal network to exchange information and experiences among themselves, such as knowledge about territorial protection and management. Another aim is to promote coordination between both states in health matters, such as achieving an intercultural health model with a cross-border approach.

One challenge the Indigenous organizations face is that both Brazil’s and Peru’s congresses are largely made up of members in favor of agribusiness. In recent years, they have pushed several anti-Indigenous and anti-environment bills, such as Brazil’s controversial time frame thesis for Indigenous lands, which could have reduced new demarcations, shrunk approved territory and opened Indigenous areas for mining and infrastructure projects.

The Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor from above on the Peruvian side, near the Peru-Brazil border. Image courtesy of ORPIO.

Last year, Peru’s Congress debated a controversial bill that sought to alter the country’s PIACI laws and reevaluate the existence of all of its Indigenous reserves for isolated peoples. The bill, which human rights and environmental experts said was legally flawed and a human rights violation, was officially scrapped in June, in part due to the efforts of the Indigenous organizations that lobbied to stop it. But similar bills are on their way. On Jan. 10, Congress managed to push through an amendment to the country’s forest and wildlife law, which José Francisco Calí Tzay, the U.N. special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples, argued could “legalize and encourage the dispossession of Indigenous peoples from their lands.”

“The congresses of Peru and Brazil have been promoting bills that are so harmful to Indigenous peoples in general, and isolated peoples in particular, that they constitute serious attacks against the life and continuity of these peoples,” Huertas said. “These are bills that seek to strip the PIACI of their territories in order to dispose of them for economic purposes, regardless of whether in this way the very existence of these peoples is threatened.”

Banner image: An uncontacted Indigenous tribe in the Brazilian state of Acre. Image by Gleilson Miranda / Governo do Acre via Flickr (CC BY 2.0).

Citations:

Voss, S. R. & Fleck, W. D. (2011). Mammalian Diversity and Matses Ethnomammalogy in Amazonian Peru Part 1: Primates. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 351: 1-81. doi: doi:10.1206/351.1

Feedback: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay