By Edward Carver

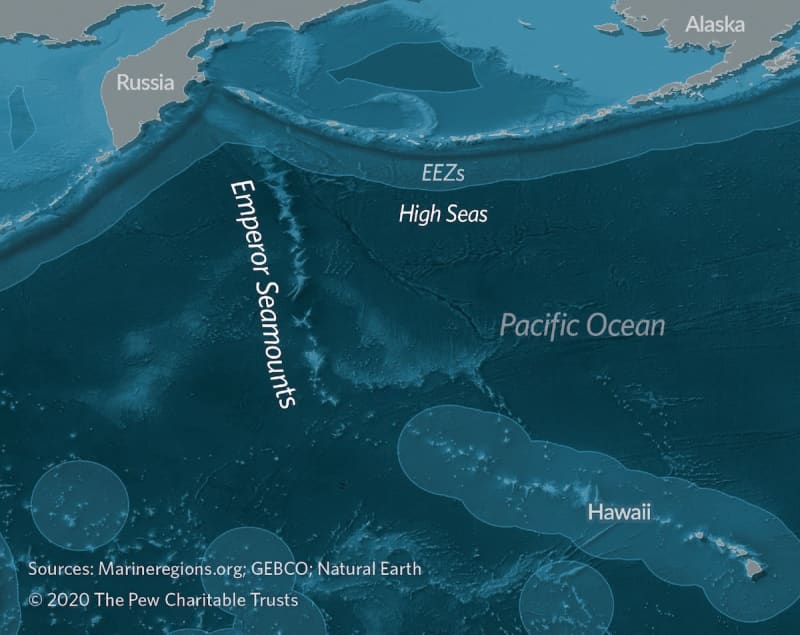

The Emperor Seamount Chain is a massive and richly biodiverse set of underwater mountains stretching about 3,000 kilometers (1,900 miles) south from the Aleutian Islands in the northwest Pacific. From the 1960s until the 1980s, bottom trawlers plied the area aggressively, decimating deep-sea coral communities and fish stocks, and removing biomass to a degree not observed on any other seamounts in the world. Fishing has decreased greatly since then, but one Japanese trawler has remained active on the seamounts in recent years — and, to conservationists’ disappointment, that trawling is set to continue.

Last week, a proposal to pause the trawling failed to reach a vote at a meeting of the North Pacific Fisheries Commission (NPFC), an intergovernmental body that manages fisheries in the North Pacific Ocean, held April 15-18 in Osaka, Japan. The U.S. and Canada put forth the proposal, which called for a pause in trawling on the entire Emperor Seamount Chain and part of the nearby Northwestern Hawaiian Ridge seamounts, pending further research.

The NPFC did pass a separate, Japan-sponsored proposal to regulate fishing of the Pacific saury (Cololabis saira), a small, short-lived silvery fish whose stock is severely depleted.

Map showing the Emperor Seamount Chain in the northwest Pacific Ocean. Image courtesy of Pew Charitable Trusts.

Efforts to protect the seamounts

The trawling pause on the Emperor Seamount Chain died during discussions before being brought to a vote because Japan didn’t support it, due to its industry’s interests, Matthew Gianni, co-founder of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition (DSCC), an umbrella group of NGOs, who attended the meeting, told Mongabay. NPFC decisions are normally made by consensus.

Gianni and other conservationists decried the lack of action on seamount protection, calling it a missed opportunity and an abdication of the NPFC’s international commitments. A principal rationale for forming the body was to protect the Emperor Seamount Chain. The NPFC formally came into force only in 2015, later than many bodies that govern fisheries in other oceans, and it has a progressive convention that explicitly mandates the protection of marine ecosystems and not just fish stocks.

“That was really forward thinking, when they were establishing this body, and to have it about 10 years later not follow through with those convention mandates, it’s very sad,” Raiana McKinney, a senior associate on international fisheries at Pew Charitable Trusts, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, who also attended the meeting, told Mongabay.

The U.S. and Canadian trawling-pause proposal included a comprehensive program of study of the seamounts’ coral and sponge communities to determine their extent and vulnerability. The proposal’s primary aim was to protect the deep-sea coral communities that serve as habitat for bottom-dwelling organisms. Deep-sea corals grow very slowly, making their populations susceptible to decline when destroyed by fishing gear. Many of the Emperor Seamount Chain coral species are found nowhere else.

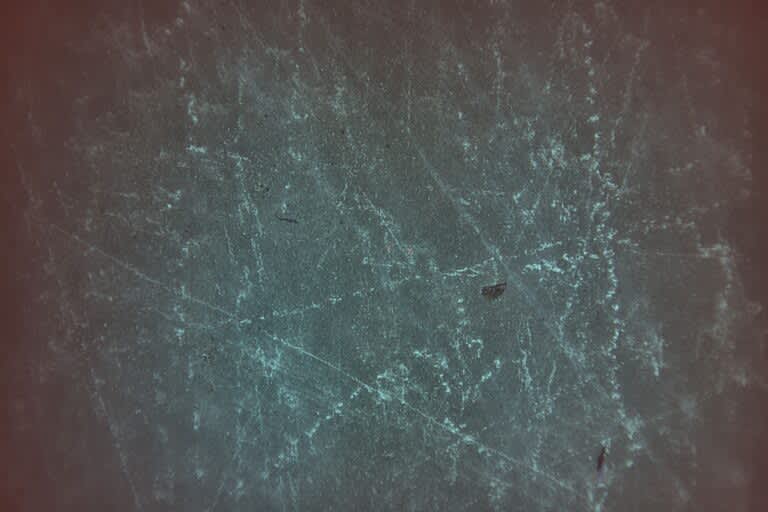

Seabed showing scars from bottom fishing on the Yuryaku Seamount in the Emperor Seamount Chain. Image courtesy of A. Baco-Taylor and E. B. Roark, National Science Foundation, AUV Sentry.

A lost “door” from a bottom trawler sits on Hancock Seamount in the Northwestern Hawaiian Ridge, just inside U.S. waters. Bottom trawling vessels drag heavy trawl doors along the seabed, a practice that’s highly destructive to seabed ecosystems. Image credit: A. Baco-Taylor and E. B. Roark, National Science Foundation, with Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory pilots T. Kerby and M. Cremer.

In addition to general ecosystem health, conservationists say a bottom-trawling ban would aid in the recovery of the North Pacific armorhead (Pentaceros wheeleri) and splendid alfonsino (Beryx splendens) fish stocks. There’s limited data on their populations but both are widely believed to be overfished, having been heavily targeted since the 1960s, and remain the targets of today’s trawling.

The armorhead isn’t found in Japan’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), so Japanese interests are keen to maintain access to it at the Emperor Seamount Chain, where the species is most abundant.

Large numbers of armorhead, which have a complex life cycle that’s hard to study, have appeared periodically on the Emperor Seamount Chain in seemingly random years. In the past, the fishing industry has ramped up trawling during those big years, most recently in 2010 and 2012. After the Osaka meeting, the door remains open to increased trawling in future boom episodes. However, a rule change implemented at the meeting will limit Japan to 10,000 tons of armorhead catch in any year and South Korea, the other nation that’s fished the area in the recent past, to 2,000 tons — limits that would be reached if a half a dozen or so trawlers were active, Gianni said.

Overall, industry interests aren’t what they once were, given stock depletion, and it’s not known whether the armorhead will again appear in the big episodic numbers of the past. Conservationists see this as a policymaking opportunity. McKinney said that now, while bottom trawling and industry interest are limited, is the perfect time to take conservation measures and create the “Central Park of the North Pacific.”

Gianni expressed hope that the trawling proposal would pass next year. In fact, DSCC and Pew are advocating for a temporary ban on all bottom fishing, not just trawling, because any contact with fishing gear can damage seabed habitat. In addition to the trawler, a Japanese gillnet vessel and a Russian pot-fishing vessel bottom fished on the seamounts in 2023. A U.S. proposal to the NPFC’s scientific committee in December included a bottom-fishing ban, but the U.S. delegation brought the narrower, trawling-focused proposal to Osaka.

The Fisheries Agency of Japan, which led the country’s delegation at the Osaka meeting, didn’t respond to a request for comment for this article.

Pacific saury on sale at a supermarket in Atlanta, Georgia, that caters to Asian-American shoppers. Image by Raiana McKinney.

Rebuilding a sorry saury stock

The rule the NPFC passed to regulate fishing of Pacific saury is the first step toward a so-called harvest strategy, to be put in place by 2027, aimed at rebuilding the stock. Saury biomass was “markedly low,” according to a 2021 stock assessment. McKinney said it’s been so overfished in the past that vessels are now just pursuing the “crumbs” of what was once there.

The new rule allows NPFC fisheries managers to reduce the total allowable catch by up to 10% per year based on stock assessments. Conservationists had pushed for 40% to give managers more flexibility, but industry stakeholders favored the less restrictive 10% option that won in the end. Still, McKinney hailed the progress, calling the proposal’s passage a “major move” toward sustainability.

Japanese people have a tradition of eating saury in the fall, and concerns that the foundering stock may threaten the tradition galvanized conservation action. Saury is also an important component of Pacific ecosystems, serving as forage fish for tunas, salmon, sharks and marine mammals.

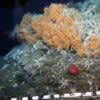

Banner image: A recovering scleractinian coral reef on Hancock Seamount in the Northwestern Hawaiian Ridge, just inside U.S. waters. Research shows that seafloor ecosystems can undergo some recovery from the effects of bottom fishing if they are protected for 30 to 40 years afterwards. Image courtesy of A. Baco-Taylor and E. B. Roark, National Science Foundation, with Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory pilots T. Kerby and M. Cremer.

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the editor of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay