A neuroimaging study has found that youth with more pronounced callous-unemotional personality traits tend to have higher gray matter volume and surface area in the anterior cingulate cortex region of the brain. But no associations between aggression and brain structure were found. The research was published in Scientific Reports.

Since the dawn of time, humans have been killing each other. Estimates state that around 1.6 million people die each year as a result of violence. While proneness to violence is a complex phenomenon, studies have identified specific risk factors that increase the likelihood that a person will engage in interpersonal violence. One such risk factor is aggression in childhood. Another important factor is callous-unemotional personality traits.

Individuals with callous-unemotional (CU) personality traits are characterized by a lack of empathy, disregard for others’ feelings, shallow or deficient emotional responses, and a lack of guilt or remorse. Individuals with these traits are often diagnosed with conduct disorder in childhood. These individuals have an increased risk of developing antisocial personality disorder later in life. The development of CU traits is influenced by a combination of genetic and environmental factors. They can be exacerbated by factors such as exposure to violence, neglect, or inadequate parenting during critical developmental periods.

Study author Nathan Hostetler and his colleagues wanted to examine how characteristics of gray matter in the prefrontal cortex region of the brain are associated with CU traits and aggression. They were also interested in observing how this association might vary with age.

The study included 54 children and adolescents aged between 10 and 19 years, 47 of whom were males. The researchers recruited participants from the community through fliers and ads, youth treatment centers, and mental health professionals. Among these youth, 20 were diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder, 6 with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, 3 with conduct disorder, one with disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, while 24 participants served as controls.

The participants completed assessments of callous-unemotional traits (the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits) and aggressive behavior (the Aggressive Behaviors rating Scale). They also underwent magnetic resonance imaging.

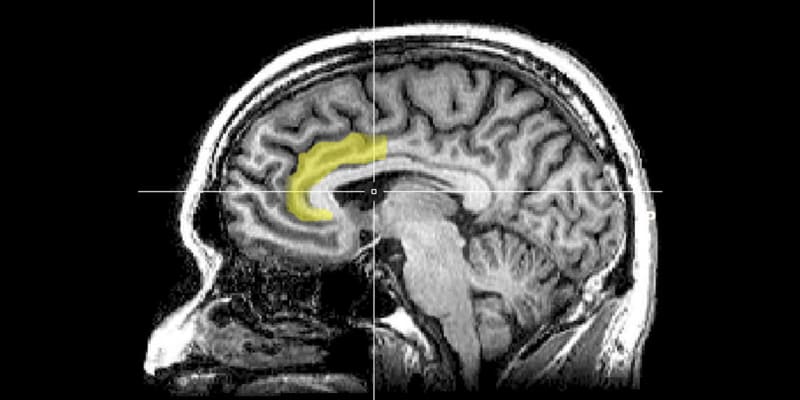

The results showed that youth with more pronounced CU traits tended to have higher volumes and larger areas in the anterior cingulate cortex in both hemispheres. However, cortical thickness was not associated with CU traits. The study found no association between aggression and the observed characteristics of the cortex.

Further analyses revealed that the association between the volume of the medial orbitofrontal cortex and CU traits increased with age. At the youngest ages examined, participants with more pronounced CU traits tended to have lower volumes in the medial orbitofrontal cortex. This association became more positive with age, indicating that older participants with pronounced CU traits tended to have higher volumes in this brain area.

The anterior cingulate cortex is a region of the brain located in the frontal part of the cingulate cortex, which plays a crucial role in cognitive functions such as emotion regulation, decision-making, and impulse control. The medial orbitofrontal cortex, situated in the frontal lobes of the brain, is involved in processing reward-related information, decision-making related to rewards and punishments, and regulating social and emotional behaviors.

“Our work suggests that CU traits/aggression in youth are related to abnormal trajectories of structural grey matter development. Specifically, we found that age moderated the relationships between mOFC [medial orbitofrontal cortex] volume and CU traits, and between mOFC surface area and reactive aggression. For all trend level or significant findings, the direction of the neurodevelopmental abnormality was consistent: in all cases, the association between grey matter structure and CU traits/aggression became more positive with age,” the study authors concluded.

“This is in line with the notion of a cortical maturational deficit or delay, in which youths with elevated levels of CU traits and aggression undergo less or delayed regressive maturation in the form of synaptic pruning. Tis would manifest as increased grey matter being associated with CU traits and aggression in later adolescence.”

The study sheds light on the morphological specificities of brains of individuals possessing pronounced CU and aggressive traits. However, it also has limitations that need to be taken into account. Notably, the number of study participants was small. This was also not a longitudinal study, but simply a study involving children/adolescents of different age. Therefore, it remains unknown whether the observed associations with age are really with age or simply reflect individual differences between study participants.

The paper, “Prefrontal cortex structural and developmental associations with callous‑unemotional traits and aggression,” was authored by Nathan Hostetler, Tamara P. Tavares, Mary B. Ritchie, Lindsay D. Oliver, Vanessa V. Chen, Steven Greening, Elizabeth C. Finger, and Derek G. V. Mitchell.