By Justin Catanoso

Drax, a major global manufacturer of wood pellets for bioenergy, has joined a California nonprofit in a controversial plan to build two industrial-scale wood pellet plants in the state. The two mills combined will be capable of making and exporting 1 million tons of pellets annually, primarily for Asian markets.

The proposed California siting of two large biomass mills would mark a major expansion of the industry outside of the U.S. Southeast, where most pellet making is currently centered. The project has raised red flags with forest advocates.

Golden State Natural Resources (GSNR), a state-funded nonprofit focused on rural economic development, has been planning the wood pellet plants for several years. Those plans received a boost in February when U.K.-based Drax, which operates 17 pellet-making plants in the U.S. Southeast and British Columbia, signed a memorandum of understanding with GSNR to be involved in the California project.

Greg Norton, GSNR’s president and CEO, said in public meetings that a goal of the nonprofit is to improve forest resiliency in rural California and reduce the risk of catastrophic forest fires, which have ravaged the state for decades.

After evaluating various options, Norton said his group decided on wood pellet making as a way of harvesting “low-value” trees and forest residue and creating economic opportunities through a product with high demand in Japan and South Korea; those two nations imported 6 million metric tons of pellets in 2021 and are poised to import far more to help meet their Paris climate agreement goals of phasing out coal.

“Our purpose is to enhance forest health, leading to forest resiliency with a long-term sustainable project primarily through science-based best practice forest thinning and treatments,” Norton was quoted as saying.

Wood chips piled in mounds more than 6 meters (20 feet) high cover the lot of the Enviva biomass plant in Ahoskie, North Carolina. Forest advocates opposed to construction of two large pellet mills in California point to the deforestation, biodiversity loss and pollution caused by the wood pellet industry in the U.S. Southeast. Image by Justin Catanoso for Mongabay.

Biomass for energy: A questionable climate solution

There is, however, little scientific consensus that forest thinning effectively reduces wildfire risk. There is also strong scientific evidence that biomass burning, while helping countries reach their Paris goals on paper, in reality adds globally dangerous amounts of unreported climate change emissions to the atmosphere.

“It’s often claimed that biomass is a ‘low-carbon’ or ‘carbon-neutral’ fuel, meaning that carbon emitted by biomass burning won’t contribute to climate change. But in fact, biomass burning power plants emit 150% the CO2 of coal, and 300-400% the CO2 of natural gas, per unit energy produced,” according to the Partnership for Policy Integrity.

Also, when harvesting forests for biomass, wood residue makes up only a small portion of pellets; instead, clear-cutting whole trees is the profitable business model used in the U.S. Southeast, where the pellet industry has been centered. Exports there total some 8 million tons of pellets annually, which is gradually reducing one of the largest U.S. forest carbon sinks and impacting biodiversity.

A potential dramatic expansion of wood pellet production on the West Coast comes as global demand surges for an energy source to replace or reduce coal use. European Union policy, for example, declares forest biomass a renewable energy source allowing for emissions to go uncounted at the smokestack.

As part of its strategy to gather forest wood for wood pellet production, GSNR has said it will promote “salvage logging” in areas damaged or destroyed by wildfire. This June 2022 photo of an area burned in the Dixie Fire, one of the worst ever in California, illustrates what salvage logging looks like. “Ecologically there is nothing worse that can be done to a forest in California than to log after fire,” said Gary Hughes, a forest advocate with Biofuelwatch. “It is likened to beating a burn victim.” Image courtesy of Kimberly Baker/Klamath Forest Alliance.

Drax, which is now building a $250 million plant in Washington state to open in 2025, appears poised to help meet growing Asian demand with the California plants. But, while the memorandum of understanding says it offers “a framework that allows GSNR and Drax to assess opportunities for joint action and confirms each party’s commitment to the vision of developing sustainable biomass initiatives,” it does not state explicitly that Drax would either build or operate the two large plants.

Drax did not respond to Mongabay’s requests for comment. The company currently manufactures about 4 million tons of pellets annually in North America, with a stated goal of producing 8 million tons by 2030.

These cut trees, viewed by California biologist and writer Maya Khosla, were harvested recently in Stanislaus National Forest, an area that falls within the potential harvest radius of a proposed wood pellet mill in Tuolumne County in central California. The mature trees were taken as part of a thinning strategy which often includes unburned forests for what is hoped to be wildfire prevention. Photo courtesy of Isis Howard.

For its part, GSNR has missed deadlines in producing a required environmental impact study and faces obstacles in complying with the California Environmental Quality Act. But it has already acquired land in Tuolumne county in the foothills of the central Sierra Nevada range as well as in Lassen county on the Modoc Plateau in Northern California.

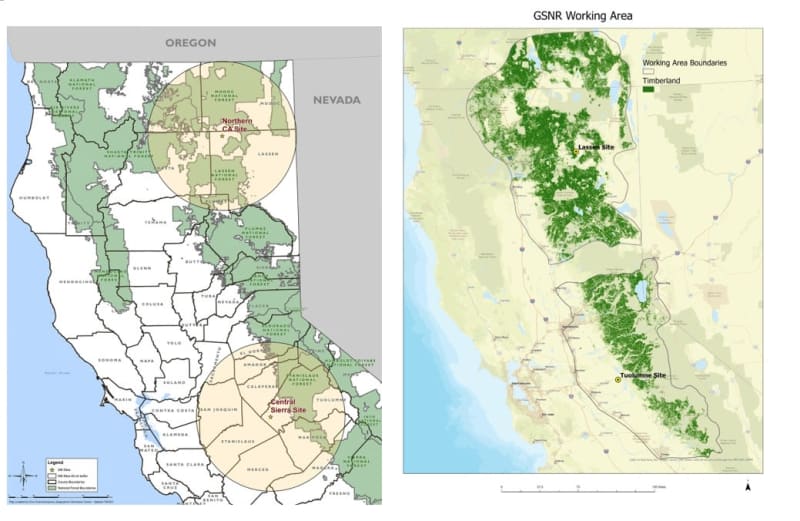

The new facilities would harvest forest within a 100-mile radius of each mill’s location, with Lassen producing 700,000 tons of pellets annually — as much as the largest Southeast plants — and Tuolumne producing 300,000 tons. California does not currently export wood pellets.

Harvest areas for the new mills would include parts of eight national forests, where logging is legally managed. Both counties have above-average poverty rates for the state and declining mining and timber industries — demographics typically targeted by pellet makers.

These maps, generated by Golden State Natural Resources and made public, show both where the proposed pellet mills would be located if approved by the state, and the harvest areas in which the mills would gather trees and forest residue for wood pellet production. Harvest areas include parts of eight national forests, which are managed by the National Forest Service for a variety of uses, including logging. Image courtesy of GSNR.

Growing opposition

While GSNR’s progress remains halting and Drax’s role unclear, opposition to the wood pellet mills is mounting.

Since June 2023, more than 100 environmental, Native American and local community organizations have filed comments with the Golden State Finance Authority (which may provide financing), opposing the pellet plants on issues ranging from damaging fragile ecosystems to increasing carbon emissions and decreasing quality of life.

“California’s forested landscapes are highly stressed by decades of industrial extraction based on a model that has depended on clear-cutting, monoculture reforestation and fire suppression,” Gary Hughes, a forest advocate with Biofuelwatch in California, told Mongabay. “Biodiversity and water resources are already on the brink, and climate change adds a new layer of challenge to forests recovering.”

Hughes added, “A new chapter of intensive forest exploitation to make wood pellets will push these globally important ecosystems beyond their breaking point.”

Felled hardwood trees and pine destined for an Enviva pellet biomass plant. Enviva, the world’s largest wood pellet energy company — which recently declared bankruptcy — long touted its green image, claiming the firm mostly used wood waste to make pellets. This photo, many others like it and statements by a whistleblower and former Enviva employee make clear that the company uses whole trees to make its pellets. That’s another reason environmentalists distrust the claim by GSNR that the California pellet mills will only thin trees and use wood residue.

GSNR’s argument that the pellet plants will provide an economic boost to otherwise depressed rural communities is challenged by the reality of the 20-some wood pellet plants operating from southern Virginia to the Deep South. Plants there are typically located in poor counties, rarely have more than 75 employees and pay mostly modest wages for high-turnover jobs.

The world’s largest pellet maker, Maryland-based Enviva with 10 plants in the Southeast, filed for bankruptcy in March, thus putting its entire workforce of more than 1,000 employees at risk of unemployment.

Typical in the Southeast are the environmental impacts the mills have on local communities due to toxic air pollution, nonstop logging truck traffic and layers of dust that settle on homes, cars and other private property for miles around the plants.

“Rural California has always been treated as a resource colony, and Lassen and Tuolumne counties are no exception,” Hughes said. “These new wood pellet plants would be the largest wood product manufacturing facilities sited and built in the state in decades. But because of automation, these projects will do little to nothing to build the community-based forest economy that both counties deserve.”

Searching for human remains in the incinerated town of Paradise, California, after the 2018 Camp Fire. In 2020 alone, some 9,900 California wildfires scorched 4.3 million acres, destroying lives, homes and habitats. 2020 saw twice the previous state record of acres burned and left California residents rattled about wildfire risk. Golden State Natural Resources argues that a growing biomass industry, which thins forests and collects forest residues to make wood pellets, would help curtail future fire threats. Forest advocates disagree. Image courtesy of Senior Airman Crystal Housman/U.S. Air National Guard.

‘Weaponizing’ wildfire fears

Despite all the opposition, wildfire risk reduction remains a potent argument in favor of biomass energy to residents of California, where a quarter of the state, or about 25 million acres, is classified as having a very high or extreme fire threat. Lassen county burned partially in one of the state’s largest wildfires a few years ago.

Rita Frost, a West Coast forest advocate with the Natural Resources Defense Council, is among those lobbying against GSNR’s plans. Years prior, she lobbied against the wood pellet industry in the U.S. Southeast.

“In the Southeast, the argument for wood pellets is about improving the sustainability of forests,” Frost told Mongabay. “Out here, it’s about forest resiliency. But by no stretch can logging and producing millions of tons of wood pellets every single year be called ecological forest management that’s going to lead to increased resiliency.”

She added, “I see GSNR weaponizing the state’s traumatic experience of catastrophic wildfires to sell their plans. It’s outrageous to capitalize on the pain and fear of local communities on the frontlines of the climate crisis. What they are calling forest resiliency is in fact intensified timber harvesting.”

GSNR cannot start construction on the mills until it demonstrates that its environmental impact study complies with California’s Environmental Quality Act. But with Drax on board as an undefined partner, the nonprofit is moving ahead as if construction will start later this year, according to its website.

If it happens, that construction may play into an ongoing discussion over the need for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to regulate the biomass industry that has simmered since the Obama presidency and may propel that debate onto the floor of the U.S. Congress.

Banner image: Lassen Meadows in the Cascade Mountain Range in Northern California could be targeted for partial harvest of forest biomass for wood pellet production. This land falls outside the protection of nearby Lassen Volcanic National Park. Image by RobertCross1 via Visualhunt.com

Justin Catanoso, a regular contributor, is a professor of journalism at Wake Forest University in North Carolina.

Citations:

John D Sterman et al 2018 Environ. Res. Lett. 13 015007DOI 10.1088/1748-9326/aaa512

FEEDBACK: Use this form to send a message to the author of this post. If you want to post a public comment, you can do that at the bottom of the page.

This article was originally published on Mongabay