By Carolina Pinheiro

Small fragments of ancestral Amazonian culture are emerging from the ground in the backyards of homes in the rural and urban parts of Parintins, Amazonas: pieces of broken pots, chips with clear drawings, elaborately sculpted figures of human and nonhuman beings, decorative objects and burial urns — all made of pottery. Among these particles of time that include stone instruments as well, people and objects are intertwined amid diverse landscapes composing an ancient biocultural mosaic called a sustainable agroecological system in archaeology.

In this municipality located on Tupinambarana Island, a “floating terrace” as researchers describe, the population of some 96,000 people are discovering remnants of what were at one time the pre-Columbian societies in the region.

The place, some 420 kilometers (260 miles) from the state capitol of Manaus, was given the name Tupinambarana by passing visitors who came into contact with the territory’s Indigenous people, the Tupinambá. Today, the collective work of scientists and local communities is filling in gaps with pieces to the historical jigsaw puzzle of this region. This new understanding is opening new paths to the study of South America’s history.

These fragments reveal important information about pre-Columbian occupation in the state and are commonly found by those living in Parintins. The city is also home to Brazil’s two most famous Boi, or sacred folkloric steer entities: the Caprichoso and the Garantido. The stage of a world-famous folkloric festival celebrating the Boi, Parintins is also becoming famous for the ancient remains driving an investigation that connects Amazonia’s past with its present.

Lago da Valéria, Parintins municipality, Amazonas. Image by Maurício de Paiva.

These archaeological sites offer a window into contexts involving food preparation like ancient gardens and kitchens. Inanimate testimonials of villages set in the past are generally found in so-called Amazonian Dark Earths (ADEs), soil concentrations filled with layers of meaningful evidence including remnants of charcoal fires, burned seeds, animal bones, human skeletons, pans, plates, pots and vases and other things.

“ADEs are formed from the gradual accumulation of organic materials. Leftover food and utensils together with charcoal show that fire was used, which is evidence of human activity. Wherever we find this type of soil, there is always much archaeological material to study,” explains archaeologist Eduardo Góes Neves, who heads the University of São Paulo’s Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

According to Neves, some of these elements correlate with methods in use today. “Agricultural methods in Amazonia were probably similar to certain current practices, including growing plants in the backyard at home — sometimes in suspended gardens that were generally hung above abandoned canoes — for medicinal use or for seasoning food.”

In the land surrounding the sites like the one in Macurany, a community in a marshy area near Lake Parananema that lies 8 km (5 mi) from Parintins’ urban area, there is a concentration of trees including Brazil nut, açai, cassava and other plants. This is evidence of anthropic forest management.

A household collection of archaeological artifacts in Santa Rita de Cássia, Parintins, Amazonas. Image by Maurício de Paiva.

Over time, this management altered landscapes and created markedly fertile soils. According to Professor Carlos “Tijolo” Augusto da Silva, an archaeologist at Amazonas Federal University, humanity’s role is to grow food together with the other creatures that share the environment. Fire is an ally in this scenario, and its adapted use guarantees that some cultures prosper.

This evidence reinforces the knowledge of original peoples that has been sustained until today: Managing natural resources promotes agro-biological diversification in Amazonia. “The Indigenous peoples developed farming techniques for many different plants, including cassava, pumpkin, açaí berry, peach palm [Bactris gasipaes], buriti [Mauritia flexuosa], babassu palm [Attalea speciosa] and Brazil nuts [Bertholletia excelsa], which are all still eaten today,” comments Tijolo.

This archaeologist says he believes that original peoples were — and still are — the doctors of the rainforest, propagating knowledge that has been passed orally from generation to generation. “These are voices that must be heard by those living in urban areas. The rainforest has a heart, and its blood is pumped from its roots. Ancient culture has suffered a secular massacre at the hands of Western society. It is fundamental to recognize [this culture] as a science of knowledge about the rainforest that helps the planet to breathe,” he states.

The plurality of species found in these fields are evidence of the collective art of caring for the land. And cassava, which is queen of the tables across all of Amazonia, has a chapter unto itself. People live near the farinha [cassava flour] mills, community meeting places maintained in the backyards of peoples’ homes.

An excavated soil profile in an Amazonian Dark Earth site in Vila Nova de Teotônio, Roraima. Image by Maurício de Paiva.

Elinair dos Santos Xavier lives in the community called Santa Rita de Cássia, located on Lago da Valéria. Her family lives on the food they grow in their field. “We are still keeping the farinha mill at my mom’s house going. We are three generations — I, my mother and my daughter — producing flour, beiju pastry, tucupi [a yellow sauce made from cassava root] and tapioca flour to sell at local businesses,” she says. The Santa Rita archaeological site is dense and extensive, occupying the top of a hill with lake access in an area full of plant species used for human consumption, including Brazil nuts, fruits like tucumã (Astrocaryum aculeatum) and inajá or maripa palm (Attalea maripa).

The recycling of organic material practiced by traditional populations feeds back into the rainforest, which renews itself. These people are agents of change and maintenance of Earth’s largest tropical rainforest. The more complex the archaeological context, the more varied the composition of plants in dynamic areas like backyards. Riverbank communities in Parintins live on top of archaeological sites where plants and pottery fragments offer a scenario for reading and understanding a multifaceted environment in constant transformation.

Family museums

More than remains left by time, these fragments make up a story of belonging that is carefully preserved by those who find them; they compose an ancestral inheritance. The people living here use them in their everyday activities like games in school. For the children, they are toys.

“I see them as memories of the ancestors, something that will be passed on to my grandchildren and great-grandchildren, because they are part of our history,” tells Elinair Xavier, who cares for 224 pieces. The display she keeps on a bookcase in her living room is one of the largest household collections in the region. “I found many of them in my backyard and others were given to me for safekeeping,” she says.

A collection of local pottery in a Santa Rita de Cássia school, in Parintins municipality. Image by Maurício de Paiva.

Xavier’s story is told among others on the pages of the book Fragments: archaeology, memories and stories from Parintins, published by GEPIA (Amazonian Education, Patrimony, Archaeometry and Environment Study Group).

The book is a path to expanding local knowledge and the memory preserved by the people who have deep contact with the artifacts, oftentimes kept in small rooms in their homes. Some keep them in drawers of bedside tables or shoeboxes, where they interact with snapshots and other treasured objects. Some prefer to place them under their pillow at bedtime to bring good luck.

The riverbank communities participating in a project developed by researchers at Amazonas State University (UEA), together with the Museum of the Amazon and the Emílio Goeldi Pará Museum, keep treasured museums inside their homes. These collections changed the life of Clarice Bianchezzi, a professor at UEA, who co-coordinates the project. “In 2015, an undergraduate student asked my help in finishing her senior thesis. That was when I visited a community and we found many of what appeared to be ceramic urns. I was impressed,” she says.

Since that time, Bianchezzi has not only included Amazonian archaeology studies in the history curriculum, but she has also held workshops on pottery production so that students gain better understanding of the elements involved in this art. “With the book, we aimed to make information available to the public as well as to look more closely at questions regarding the maintenance of these found remains in household museums inside the communities,” she says.

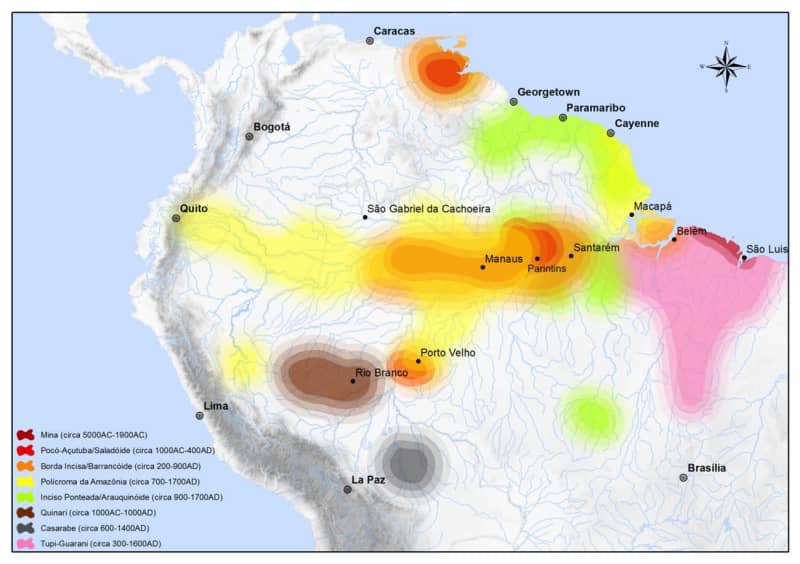

The above map shows the locations of the many archaeological pottery sites in Pan-Amazonia. Image courtesy of Lima, Barreto and Jaimes-Betancourt, 2016.

Archaeology, a path to learning about the world

Michel Carvalho Machado is a professor in the Pará Modular Indigenous Learning Organization System. His research directly influenced the conception of the project that became a book. He holds a master’s degree in sociocultural diversity from the Emilio Goeldi Museum and decided to study children’s relationships with these found pottery objects.

Born and raised in Parintins, Machado based his research on his personal family experience with these objects. “I remember my dad and grandfather talking about these fragments on the front porch when I was still very young. We have a family collection with some 300 objects that have been in my family for four generations,” he comments.

He says all the pieces were catalogued and later registered at the National Institute of Historic and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN). “They may still become part of the collection at the Parintins Museum, which is expected to be inaugurated in 2024,” adds the researcher, who also happens to be the first person from his community to become an archaeologist.

Machado explains that the artifacts hold important clues about the complex pottery production technology used by the original peoples. Also, the graphic images found on the pieces, which date up to 3,000 years ago from the archaeological phase called Pocó-Açutuba and Konduri, show a connection between past populations and those still living in the region. “Many of the traits we see in the body painting used by Indigenous groups are evidence of those connections,” he points out.

A piece from the collection of Michel Carvalho Machado, Parintins’ first archaeologist. Image by Maurício de Paiva.

These clues allow us to conclude that the communities were part of a complex trade network. Macro-regional stylistic patterns emerged in the sociocultural relationships between peers in their production of objects — what we call tradition.

There are 44 archaeological sites registered in the Parintins Archaeological Map, made by GEPIA. There are pottery pieces dating back to the Pocó-Açutuba, Marajoara, Globular and Konduri styles in the region, which were probably still manufactured at the time of the European invasion.

Michel Machado points out that almost no one in the urban part of the city has contact with these archaeological artifacts but that because of the high concentration of dark earths in rural areas, interaction is part of daily life. Legacies from old ways of living come to life in the day-to-day of the people who use their inheritance in an intuitive manner.

He says children are the biggest contributors to collections in rural communities. “They find fragments when they play and dig in the soil. Schools like Marcelino Henrique [located in Santa Rita de Cássia] also put together collections, holding contests to see who can find the most artifacts. This motivates kids to learn more about them,” he reflects.

Publication of the study, which was the first to look at ancient pottery from the region in a more plural context, generated visibility for Parintins, which in turn generates better conservation of the artifacts. “Since 2005, mostly because of Helena Lima’s research inside the communities, people have begun to understand that the artifacts belong where they are. So today, they make replicas for selling to tourists instead of selling off the original pieces,” Machado explains.

More than just recording history, archaeology can offer many solutions to current conflicts. For the Emílio Goeldi Museum’s resident archaeologist Helena Lima, creating a new sort of relationship between museums and traditional empirical knowledge is the best way to preserve these and other pieces of historical evidence. Her life is dedicated to research in Amazonia.

“In 2004, I was invited to Parintins for the first time by IPHAN. I remember an elderly person who didn’t want to allow me to do my work because of other archaeologists who had come through and taken away all the funeral urns they had found there. They completely took away the community’s access to the material. It was obvious to me that archaeology needed to change the way it related to communities.”

Archaeological remains found in Santa Rita de Cássia, Parintins, Amazonas. Image by Maurício de Paiva.

Since that time, Lima has been carrying out a broad study in the Lago da Valéria region on the history of so-called “little faces,” in which she analyzes different aspects of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic representations (figures that resemble humans and animals) drawn on the pieces.

“Pottery is a powerful tool for understanding social communication. It dialogues with the past, revealing characteristics from which we can understand who these people were. Some are very similar even though they were found in geographically distant locations. This means there was contact between the groups. They also show us which techniques were particular to each group of people, sort of like grandma’s cake recipe, which no one else knows how to make,” she explains.

Teotônio, a portrait of human persistence

Silvana Zuse is an archaeology professor at Rondônia Federal University (UNIR) and studies pottery from the Madeira River. Her findings have been similar to Lima’s. “Even though the Tupi-Guarani peoples originated in Rondônia, we have found technical differences and similarities, like the type of wood used and firing, which is done in open fires in other parts of the country.”

UNIR’s technical collection has a number of collections from across the state of Rondônia, especially the Madeira River region. A good share of the artifacts were collected during periods of preventive archaeological studies because of roadway or transmission line construction or other works, mostly over the last 10 years. “There is a wide variety of archaeological material ranging from the oldest, which date to 9,000 years [BP], to the phases ranging from 3,500-500 years [BP]. The collection is strongly associated with the deep and continuing Indigenous presence in the region, with very culturally diverse stone and pottery materials. Some are related to the historical period when the Madeira-Marmoré Railway was built,” explains Zuse.

A pottery specimen from Rondônia Federal University’s technical collection. Image by Maurício de Paiva.

The researcher also comments on archaeological sites like Teotônio, on the upper Madeira River, where the local population was affected by construction of the Santo Antonio Hydroelectric Plant. The people who lived there and cared for the territory were removed from the land.

“There are two archaeological sites there, one on each side of a waterfall. On the left, there is a large concentration of black earth mounds, round ones, around the central square. The site has a great deal of botanical material and charcoal. The environmental impact [study] allowed for mining in the area and a lot of scientific evidence ended up being lost,” Zuse says.

Archaeologist Thiago Kater is witness to the changes that happened in Teotônio. Curious about the history of populations that had no systems of writing, he earned a master’s degree and Ph.D. on the region. He clarifies that this region, which lies near the capital city of Porto Velho, forms a sort of peninsula and a plateau where there is evidence of human occupation dating to approximately 9,000 years ago. A waterfall existed there until 2012 that had a long history of impressive numbers of fish populations. Before being flooded by the dam, people could be seen catching fish with their hands there.

“The waterfall, which was never navigable, was an essential element that organized life around it; its flooding interrupted a process that had been going on for thousands of years,” the researcher stresses. The intense traffic of people attracted by the abundance of fish there means these two sites are rich in pottery fragments from nearly all the pre-Columbian Amazonian periods. “Teotônio can be considered a microcosm of the region, a geographical and symbolic landmark.”

There, the entire sequence of Amazonian pottery technology can be seen, including the Pocó-Açutuba and Jatuarana subtraditions, which belong to the Polícroma da Amazônia tradition — both are pan-Amazonian, meaning they are found in regions outside the boundaries of the Legal Amazon. This abundance of historical elements makes Teotônio a school-site because extensive research can be carried out in just one location.

The Teotônio archaeological site in Roraima. Image by Maurício de Paiva.

The Upper Madeira Project, or PALMA, is coordinated by archaeologist Eduardo Góes Neves together with Professor Fernando Almeida from Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ). Amazonia’s best continuous records of Dark Earth formations have been found in Rondônia. “The site is immense and we still don’t know how large an area was occupied. What is most important is that we can use this material for many years of study,” Neves states.

The research is part of a study in the region titled “Indigenous Peoples and the Environment in Ancient Amazonia (PIMA)”, also led by Neves together with Professor Francis Mayle from Reading University in the U.K.

The people living in the New Teotônio Villa take part in the digs. “We make it a point to work with them when we are excavating. The residents of the villa also help us with logistics; some participate in the digs, including the Tenharim and the Kawahiva, two Tupi-Guarani peoples from this region,” Neves says. Fieldwork at the site brings together professors and students from different universities, including UNIR, which has some 2,000 pieces from the site in its collection.

An uncertain future

Still, sites like those in Rondônia and Parintins are at risk not only because of urban sprawl and infrastructure works, but also because of the climate changes affecting Amazonia. Márcio Astrini, executive secretary of the Climate Observatory, comments on the fact that we have not slowed global warming and continue cutting down trees.

“These two factors are bringing the rainforest closer to its point of no return, or in other words, to collapse. The drought that hit at the end of last year was a slap in the face for humanity, a taste of things to come,” he affirms.

Astrini says he believes we must see the forest as a single living organism — a body whose organs are not functioning so well anymore. Over time, the accumulation of these small malfunctions will cause the body to stop working. “You don’t just wake up one day out of the blue with everything sideways. These changes worsen progressively until they become dramatic. Unfortunately, that’s what we are seeing in the Amazon today.”

This reality is placing the existence of Amazonian Dark Earths and the ecosystem services that they offer at risk. As Neves says, “there are still concrete solutions for Amazonia, and understanding the past can help plan for a sustainable future there.”

This report is part of the “Amazon: Fire Against Fire” project and was produced with funding from the Rainforest Journalism Fund together with the Pulitzer Center. Journalist Gabriela Di Bella collaborated on this report.

Banner image: a piece from a private collection in Santa Rita de Cássia, Parintins, Amazonas. Image by Maurício de Paiva.

This story was reported by Mongabay’s Brazil team and first published here on our Brazil site on Apr. 22, 2024.

This article was originally published on Mongabay