Four years on from the 2019 protests and unrest, Hong Kong was finally able to legally restrict the performance and distribution of the movement’s anthem Glory to Hong Kong – a move that its composer foresaw back in 2020.

But why is the song controversial, and where did it come from? How did the government win at the appeals court? Was the song already illegal? And how did YouTube seek to comply with the legal ruling?

HKFP examines how the government enacted the ban, and how a city – once a bulwark of free expression in Asia – came to insist that a song was a threat to China, the world’s second-largest economy.

Where did the song come from? Is it pro-independence?

Glory to Hong Kong was released on YouTube by a local songwriter named Thomas, and his team, on August 31, 2019 – during the height of the citywide pro-democracy demonstrations and unrest. It featured lyrics co-written by users of online discussion forum LIHKG. They called for democracy and freedom, and included the now-banned protest slogan: “Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our times.”

Though the authorities say the song is linked to calls for Hong Kong independence, there is no mention of this in the lyrics, nor was independence an official demand of the 2019 movement.

“For all our tears on our land, do you feel the rage in our cries,” the lyrics say. “Rise up and speak up, our voice echoes, freedom shall shine upon us.”

Ten days after it’s release , the song’s popularity skyrocketed when football fans belted it out during a match between Hong Kong and Iran, after booing the Chinese national anthem. In the months that followed, it was often played on loop during street demonstrations, or formed part of mass “Sing With You” gatherings at shopping malls.

The mall singalongs were favoured by “wo lei fei” – people who preferred peaceful means of fighting for civil rights, as opposed to the vandalism and violence which gripped parts of the anti-extradition law movement.

In addition to the scrapping of an extradition treaty with China, demonstrators demanded full democracy, an independent probe into police conduct, amnesty for those arrested, and a halt to the characterisation of protests as “riots.”

In all, the Appeal Court ruling restricting the song said it had been heard at 413 public order events, “some of which involved violent and other unlawful behaviour and the chanting of secessionist or seditious slogans.”

Is Glory to Hong Kong illegal?

Yes and no. In May 2024, Justice Secretary Paul Lam said that – even though the court had issued a ban on certain acts linked to the song – it should not be regarded as a “forbidden song.”

Days earlier, an injunction order banned people from “broadcasting, performing, printing, publishing, selling, offering for sale, distributing, disseminating, displaying or reproducing” the song with seditious intent, with the aim of advocating Hong Kong independence, or with the goal of suggesting it was China’s official national anthem.

The judges said the order was “necessary” to persuade online platforms to remove the “problematic videos.” However, there were exceptions made for academic and journalistic purposes, as long as there was no unlawful intent as described above.

Previously, the High Court had rejected the government’s bid to restrict the song, saying the move could have a “chilling effect” on free speech. But the authorities were given a chance to challenge the court’s decision and won.

In response, a spokesperson for China’s Foreign Ministry said that “[s]topping anyone from employing or disseminating the relevant song… is a legitimate and necessary measure by [Hong Kong] to fulfil its responsibility of safeguarding national security.”

Lam said online platforms would be encouraged to respond to the ruling: “Now the court order clearly defined utilising this song with the intent of sedition is illegal, its very clear. [People often ask] what the red line is. Now the court has told you,” he said in Cantonese.

Wasn’t Glory to Hong Kong already illegal?

Before the May 2024 court ruling, the government had refused to say whether Glory to Hong Kong was illegal when asked by HKFP, despite also insisting that the law was clear.

There were nevertheless multiple legal moves involving the song. Last July, Cheng Wing-chun was jailed for three months after becoming the first person to stand trial under the new anthem law. Cheng replaced China’s national anthem with an instrumental version of Glory to Hong Kong in a video showing Hong Kong fencer Edgar Cheung receiving a gold medal in the Olympics in 2021, making it the first court ruling related to the protest anthem.

Hong Kong’s national anthem law, which criminalises insults to March of the Volunteers, was enacted on June 4, 2020 – violators risk fines of up to HK$50,000 or three years in prison.

Weeks later, on June 30, 2020, Beijing inserted a national security law into Hong Kong’s mini-constitution which criminalises subversion, secession, foreign collusion and terrorism.

Days after that, the government said the 2019 protest movement’s “Liberate Hong Kong” slogan had pro-independence meanings, a crime under the security law, despite the fact that independence was never a demand of the 2019 movement. During the city’s first national security trial a year later, the court ruled that the “Liberate Hong Kong” slogan was capable of inciting others to commit secession.

On July 8, 2020, a little over a week after the national security law was enacted, the Education Bureau banned students from playing, singing or broadcasting Glory to Hong Kong on campuses, saying it contained “strong political messages” and was closely linked to violence and other illegal acts.

No-one in Hong Kong schools should “hold any activities to express their political stance,” the education chief said at the time.

In the years since the protests, buskers known for singing the song have been arrested for “public disorder” or targeted for performing without a permit. One was cleared of wrongdoing, whilst the trial of another is still ongoing.

Another man was arrested for suspected “sedition” in 2022 after sharing a video linked to the song.

Has the song been wiped from the internet?

No. As of late May – following the court order – multiple instances, in multiple languages, remixes and formats remain available to Hong Kong users across several platforms.

Nevertheless, a week after the ruling, Google geo-blocked Hong Kong users from accessing 32 instances of the pro-democracy protest song listed in the court order. It came after Secretary for Justice Paul Lam said the government was “anxious” to see the tech company’s response.

The 32 clips were replaced with a message on YouTube stating: “This content is not available on this country domain due to a court order.”

“We are disappointed by the Court’s decision but are complying with its removal order by blocking access to the listed videos for viewers in Hong Kong,” a spokesperson for YouTube said in a statement sent to HKFP. “We’ll continue to consider our options for an appeal, to promote access to information.”

YouTube said it had clear policies for removal requests from governments around the world, restricting content as a response to legal processes. In addition to the 32 takedowns, links to the videos on Google Search will no longer be visible to users in Hong Kong, it added.

Despite the blocks, the tech giant said it shared the concerns previously expressed by human rights organisations about the chilling effect of the court order.

New uploads, not included in the court order, continued to appear on YouTube – accessible to Hongkongers – days after its statement.

Did the ban bring more attention to the song?

Most likely, yes. Internet commentators and columnists have suggested that the government’s legal bids to suppress the song have led to unwanted renewed interest in something that may have otherwise been forgotten.

Following the first talk of a ban, Glory to Hong Kong ended up dominating the Apple iTunes Top 10 for Hong Kong before its temporary removal by the uploader.

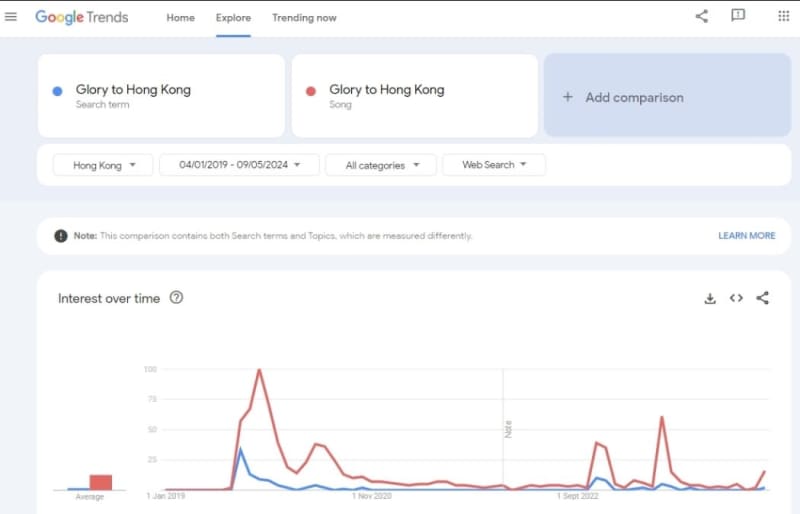

Google Trends, a tool which measures the frequency of search queries, suggests upticks in interest which correlate with times when the song had been misplayed at sporting events, or when the government has published press releases or made legal moves against it.

The risk was even mentioned during the legal proceedings. During an injunction hearing last year, Senior Counsel Abraham Chan warned that, by seeking to prohibit unlawful acts relating to Glory to Hong Kong, it had only drawn more. The injunction application, Chan said, “would bring about an own goal” and risk the “Streisand effect.”

The “Streisand effect” describes the unintended failure of an effort to conceal information. The term was coined after American singer Barbra Streisand drew greater attention to photographs of her home in California after filing a lawsuit in an attempt to conceal the photos from the press.

Chan also said that the court had to consider the “chilling effect” that the injunction would bring. “You can’t simply wave the card of national security, to say don’t worry about chilling effect,” said the senior counsel.

How was the song confused with the national anthem?

Many pro-democracy protesters viewed Glory to Hong Kong as an alternative or potential anthem for Hong Kong, and – in the years that followed – it has been confused with the city’s actual national anthem, which is that of mainland China’s. According to the May 2024 court ruling, it had been presented as the city’s official anthem no less than 887 times, “including in some international sports events.”

A months-long series of mix-ups began in November 2022, when Glory to Hong Kong was played at a Rugby Sevens game in South Korea after an intern reportedly downloaded it from the internet. Whilst the Hong Kong government demanded a “full investigation,” one Hong Kong lawmaker even demanded the person responsible be extradited to the city.

“The National Anthem is a symbol of our country,” a government spokesman said in response. “The organiser of the tournament has a duty to ensure that the National Anthem receives the respect it warranted.”

Meanwhile, the Hong Kong Rugby Union (HKRU) said in a statement: “The HKRU expressed its extreme dissatisfaction at this occurrence and has received a full explanation of the circumstances that led to this. Whilst we accept this was a case of human error it was nevertheless not acceptable.”

In the weeks that followed, two instances of Glory to Hong Kong being mislabelled as the “national anthem of Hong Kong” occurred in televised footage at other rugby events. It led to sporting authorities issuing guidelines to ensure athletes made a “time out” gesture if the offending song was played.

Just weeks later, another anthem blunder occurred at the Asian Classic Powerlifting Championship in Dubai. In December 2022, local gold medallist Susanna Lin made the “time out” signal as the protest anthem was played during her prize-giving ceremony.

A Hong Kong sports official rejected an apology from organisers, and the Organized Crime and Triad Bureau launched a probe.

Yet another mix-up occurred last February at an ice hockey game in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Several Hong Kong hockey players at the World Championship Division III Group B match made the “time out” gesture as the offending song was played following their victory over Iran. The audio was halted and the correct anthem was played after around 90 seconds.

Local sports associations now must collect an anthem toolkit from the Sports Federation & Olympic Committee of Hong Kong, China each time they set off for an international sports event. It contains two regional flags, two hard copies of the anthem – either computer disks or a USB drive – as well as an acknowledgement receipt for event organisers to sign.

Meanwhile, guidelines have been tightened further, with sports teams now expected to boycott any event in which the anthem cannot be inspected in advance.

Why was Google singled out?

The government and state-backed media eventually pointed the finger at search giant Google, after investigations concluded that sporting event staff had downloaded what they believed to be the city’s anthem from the internet.

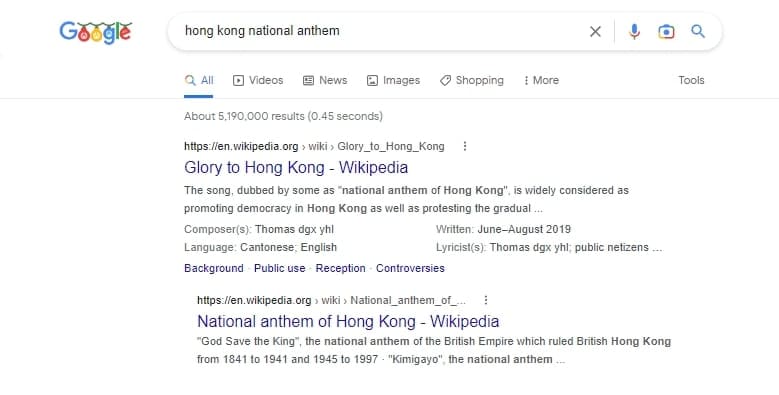

Until recently, search results for “Hong Kong national anthem” would often list the Wikipedia page for Glory to Hong Kong at the top, prompting protests from the local authorities.

In December 2022, top officials – including Chief Executive John Lee and security chief Chris Tang – criticised the US firm after it failed to comply with a government request to change the search results.

According to Tang, Google said their results were generated by an algorithm with no human intervention: “We have approached Google to request that they put the correct national anthem at the top of their search results, but unfortunately Google refused… We felt great regret and this has hurt the feelings of Hong Kong people.”

Tang said that Google provided paid advertising services to allow specific results to appear in prominent places. He also added that Google faced a European Union legal ruling requiring it to remove incorrect search results from its site.

With the tech firm refusing to budge, the government updated its English-language web page with anthem details last April, months after the anthem row erupted. Since then, it has appeared as the top search result, when checked by HKFP.

Google has previously vowed to decline data requests made under the security law, and left China amid rising internet censorship in 2010.

Last year, Secretary for Innovation, Technology and Industry Sun Dong said: “Google said you must have evidence to prove that [the song] violated local laws, that [we] needed a court order… Very well, since you brought up a legal issue, let’s use legal means to solve the problem.”

Following the May 2024 court ruling, Google agreed – not only to geo-block 32 instances of the song on YouTube – but also said it would restrict their presence in Google results.

What do tech and telecom firms say?

Meta, Spotify and other streaming firms did not respond to HKFP’s requests for comment, or referred questions to a representative body – the Asia Internet Coalition.

Following the legal restrictions, the coalition told HKFP that it was “assessing the implications of the decision and how the injunction will be implemented.”

“We believe that a free and open internet is fundamental to the city’s ambitions to become an international technology and innovation hub,” it added.

What does the composer say?

In a 2020 interview, composer Thomas told HKFP that he thought a ban was inevitable: “We had anticipated that the government would be that unreasonable and suppress citizens’ voices, by fair means or foul… Maybe it will go more underground, but it will not disappear completely. I think everyone will remember this song.”

He added that people would not back down easily in the face of what he called an “unreasonable request.”

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team