By Alex Johnson

This article first appeared on the blog of Museum Hack. If you want your content to be featured in CulturaColectiva, click here to send a 400 word article.

I’m not sure why, but I recall thinking a lot about cannibalism pretty early in my life. There are probably a couple of reasons for this. One is that I saw the 1993 film Alivewhen I was pretty young. The other is that I grew up catching lobsters, and those f**kers love eating each other.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not interested in eating people (I hear we’re very salty). Rather, I’m fascinated by the intersection of civilized human composure and animal survival. With enough stress and hunger, people stop being “human” and start being lobsters, so to speak.

Relacionado

How Long Was The Shortest War In History? Far Shorter Than You Can Imagine

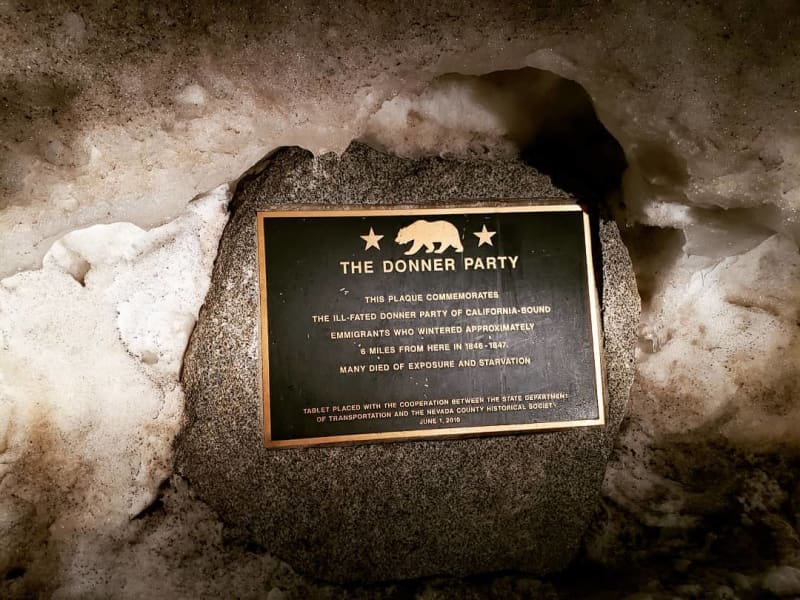

The Donner Party, then, presents both a great opportunity to examine where this human-animal intersection might occur, and it's also an Icarian tale of human pride in the face of nature’s cold nihilism. When John L. O’Sullivan coined the term “manifest destiny” in The New York Post, he hypothesized that God in Heaven, the Sky-Man Himself, wanted Anglo-Americans to take the West.

But, in 1846-47, the wilderness gave the Donner Party an answer to O’Sullivan’s assured hypothesis: “There ain’t no God out here.”

Where We’re Going, We Don’t Need Roads

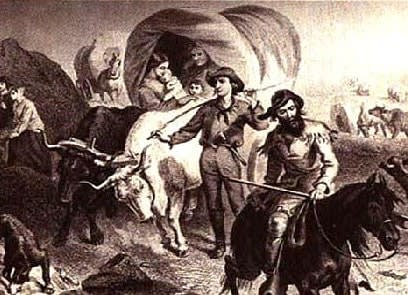

The Donner Party story began, as all great tragedies do, with hope. It starts in Springfield, Illinois, in 1846. The hot new thing was uprooting your whole life and traveling in numbers 2,500 miles west to find the promise of an unfamiliar place with less-developed infrastructure: California.

An optimistic plan, then, concocted by an Illinois businessman named James Frasier Reed, seeking to be even more successful in the rich lands down Californee-way. Also, his wife, Margaret, was prone to nasty headaches, and maybe she’d feel better near the ocean? Sure, why not?

Relacionado

The 8 Deadliest And Most Gruesome Epidemics In Human History

Reed wrassledupa group of about 32 fellow travelers—other families, hired hands, etc.—to join his quest for nicer weather and more money. James was pretty sure this trip would be cake, since his family’s wagon was nicer than my apartment: two stories, an on-board iron stove, sleeping bunks, suspension seats. Granted, it didn’t come with a dishwasher, but neither did my apartment. Reeds’ oxen probably weren’t too jazzed about pulling a nomad-palace for 2,500 miles, but then this isn’t a story about oxen having a very good time, is it?

Check out this article’s sources for a full rundown of who joined the party exactly, and when and where they joined it. For the sake of keeping things digestible: it was a bunch of people, and James Reed was one of the ringleaders. This group also included a couple of other families: brothers George and Jacob Donner and their families.

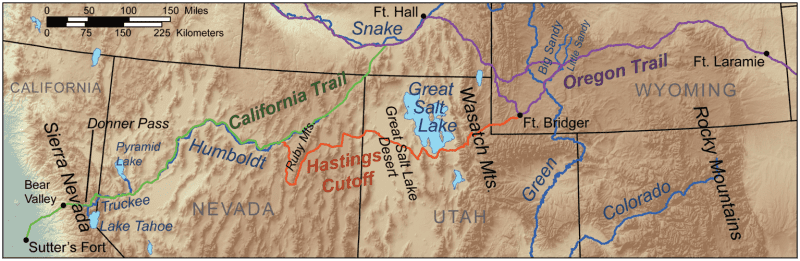

The Donners—and James Reed—owned a book called The Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and Californiaby Lansford W. Hastings. Their takeaway was what the author named the “Hastings Cutoff.” Basically, it was this great shortcut through the Great Basin—which covers most of modern-day Nevada, and good chunks of other states like Oregon and Utah. The Hastings Cutoff promised to shave a good 350-400 miles off the trip, and the terrain was supposed to be nice and easy.

That sounded like a solid deal, but this was well before Amazon reader reviews. Hastings’ shortcut was, in fact, untested and completely false. But Reed’s wagon train didn’t know that, so off they went. The irony: Hastings actually set off eastward, from California, around the same time that Reed and his wagon train started heading west. Hastings had decided to finally test out his shortcut at the exact same time that another group was unwittingly doing the same.

The Trip Before the Fall

Along the way, the group picked up followers, swelling their number to 87 at its largest point. It was a long trip that required provisional stops in places like Independence, Missouri. The wagon train connected with another train led by Colonel William H. Russell. It was a bit like a traveling carnival, but with less kooky stuff in it, and more families with kids.

If you’ve ever played Oregon Trail, you know that you’re gonna lose a couple of people to consumption along the way, even if you do everything right. This happened along the way, starting with Reed’s mother-in-law, who died of consumption. A bummer, certainly, but this probably didn’t have a huge impact on morale. It was early in the trip, and she actually had consumption before they left.

Relacionado

Gruesome Medieval Images That Rekindle Our Fascination With Death

By June 27, 1846, the group had reached Fort Laramie (in modern-day Wyoming). They arrived one week behind schedule, which isn’t bad. On the way there, however, Colonel Russell had resigned his post as wagon-train captain and was replaced by a guy named William Boggs.

James Reed found a great piece of advice from an old friend at Fort Laramie. James Clyman, also from Illinois, had just done Hasting’s Cutoff with Lansford Hastings himself, and was on his way back east. “F**k. That. Route.” said Clyman, basically. He claimed the path was barely walkable, let alone good for wagon wheels; and then there was a great desert and the Sierra Nevada mountains just afterward. “Just stick to the regular route. Don’t be an a**hole,” said Clyman, maybe.

Man-Flesh Destiny

People believe what they want to believe. Clyman’s advice was solid, but boy, did he want Hastings to be right. He got the positive reinforcement he was looking for on July 11, 1846, when the group ran into a different man in Fort Laramie. This man was carrying a letter from Lansford Hastings. Hastings had written it at the Continental Divide (think: Rocky Mountains). Reed’s know-it-all hero would meet Reed and the rest of his wagon train at Fort Bridger, and lead them through his shortcut.

It was just what travelers like Reed wanted to hear: contrary to Clyman’s warnings, the Hastings Cutoff was real, and Hastings himself would lead them through. Others, however, remained skeptical. On July 19, when the wagon train reached Little Sandy River in what is now Wyoming, the party split. Most folks just took the normal route. But Reed and others set off north, for Hasting’s Cutoff. This group elected George Donner as its leader, thus becoming the “Donner Party.”

Relacionado

Here's The True And Bloody Story Behind The Origins Of Thanksgiving

The Donner Party didn’t find Lansford Hastings at Fort Bridger, but he’d left a note that he’d set off already with another group, and that followers should catch up. Jim Bridger, who’d established the fort, also vouched for the Hastings Cutoff. The travelers felt encouraged to continue after a few days’ rest at the fort. The rest of the journey, they figured, would take about seven weeks.

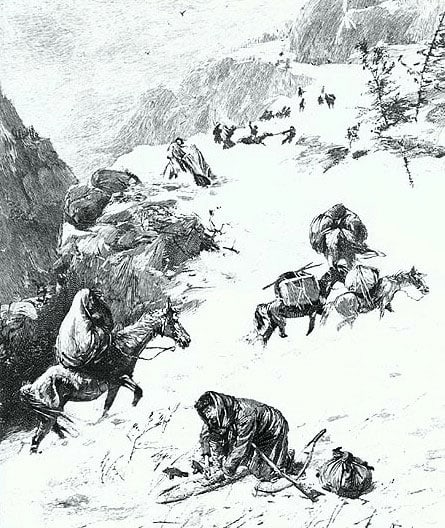

Soon enough, it became clear that seven weeks wasn’t happening. The “trail” was arduous. At some points, the wagon train was making fewer than two miles per day, forced to fell trees just to clear a path. At other points, wagon wheels sank into the Great Salt Lake Desert, where the train lost 32 oxen and several wagons, entirely. With 600 miles left to go, the Donner Party realized they wouldn’t have enough food. They reached the Humboldt River on September 26, as snow began to fall across the mountains. A couple of men were sent ahead to California to bring back supplies. The rest of the train continued on more slowly.

Tensions mounted and came to a head on October 5. At Iron Point, a couple of wagons became tangled up. A hired man who was driving one of the wagons began whipping his oxen so forcefully that James Reed ordered him to cut it out. The man refused, so James Reed stabbed him in his guts, killing the man. Reed was voted off the island, so to speak, and rode off west with another man.

The Donner Party continued on with exhausted draft animals, and everyone who was able walked on their own two feet. On October 7, a German member of the caravan named Lewis Keseberg kicked an old Belgian man out of his wagon. The Belgian man, shunned from the other wagons and unable to walk, was left under a tree to die. Things got even worse on October 12, when Piute Indians attacked the Donner Party, killing 21 of their remaining oxen with poison-tipped arrows. Like I said: this story isn’t too kind on oxen.

Shortly after reaching present-day Reno, one of the guys who had set off to find supplies in California returned with provisions and Native American guides. They also brought news of a new path through the Sierra Nevada mountains. It was so encouraging that the Donner Party stopped for five days to rest their remaining oxen before making a final 50-mile push over the summit. They shouldn’t have done that.

Relacionado

The Pirate Writer Whose Life Of Adventure Ended In Tragedy

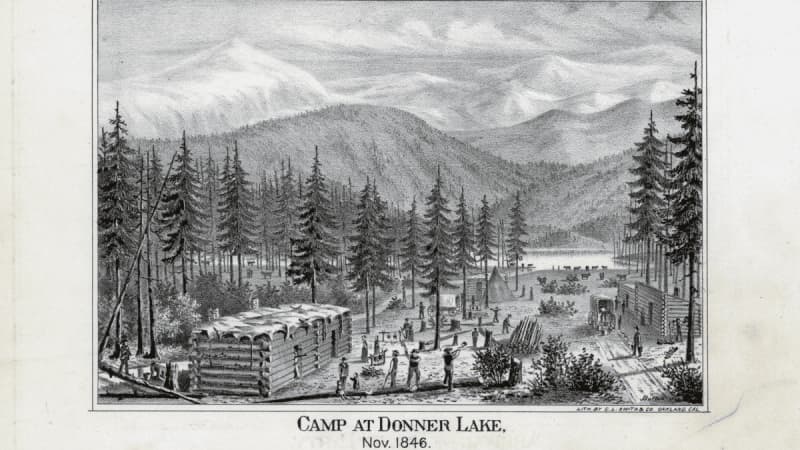

After the rest, the party made their way to the base of the mountain summit. Along the way, the Donner family lagged behind the rest after a broken axle forced them to stop for repairs. Twenty-two people remained behind as the rest of the party continued to Donner’s Lake (well, that’s what we call it now, anyway). As they reached the lake, snow began to fall. Just 12 miles from the Sierra pass, they were stuck, and the early snow wasn’t melting.

Aaand this was where the cannibalism started. Not right away, of course. There were still oxen to be slaughtered, but they killed the last of those on November 29. Another five feet of snow fell the next day. Clearly, the Donner Party, now split into groups, was stuck here for the winter with no food.

Relacionado

Dark Truths Hiding Behind The American Dream: The Photo League’s Radical Photography

They boiled lots of stuff that wasn’t food in a vain attempt to turn it into food. Twigs, bones, leather, bark—not a lot of nutritional value in these things, it has to be said. But hunting wasn’t working, and you gotta eat something, right?

As blizzards set in, and folks started dying, cannibalism started to make some sense. A dead person, once a companion, was now a frozen protein source. The survivors made the same choice that many other unfortunate explorers had made at sea and elsewhere: eat the dead so that the living might survive.

Leftovers

By eating the fallen, many in the Donner Party managed to survive the winter—just barely—and were discovered by a series of staggered rescue parties stretching from February 16 to April 17. Each party rescued different groups of victims, and each found similar nightmares.

The first party reached Donner Lake on February 19 and found 12 dead and 48 survivors, barely clinging to life and sanity. The second relief party reached the lake on March 1 and found the unsettling remains of cannibalism. They attempted to rescue more survivors, but were themselves caught in another blizzard and forced to leave others at a spot known as the “Starved Camp.” A third relief party found Starved Camp on March 12, finding more signs of cannibalism—including the body of Isaac Donner.

The final relief party reached the camps on April 17. Only one man was left: Louis Keseberg. He was alone, save for the mutilated remnants of his fellow travelers. Keseberg was the last survivor to be brought to Sutter’s Fort, arriving April 29.

All told, two-thirds of the men who opted to try out Hasting’s Cutoff wound up dead, with at least some eaten post-mortem. One-third of the women and children met similar fates. The press was . . . not great. Newspapers across the country printed stories and diaries from the Donner Party, detailing all the murder and cannibalism, and other things that make people afraid. Guys like Lansford Hastings and James Reed took their share of the blame for not heeding advice, using poor judgment, and getting all these people killed—while somehow surviving the ordeal themselves. It was enough to curtail the rush to California (until gold was discovered there the following year, of course).

So, what have we learned from the Donner Party expedition? Two things, I think. One is that cannibalism may be taboo, but it’s something all people are capable of given the circumstances. I mean, people gotta eat.

The other is that The Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and California by Lansford W. Hastings is a dumb, bad book, and don’t read it. One star.

Do you know of other hidden episodes of world history? Click here to send a 400-word article and let our millions of followers know you!

For more articles like this, click on the following links:

4 Reasons Why You Should Get Married At A Museum

The Phenomenal Open Air Contemporary Art Museum In The Brazilian Jungle

5 Things You Can Do Right Now To Become A Better Writer