While many laws have been created and updated to improve the lives of women in Japan, others have not. Here we highlight four laws we would like to see amended so Japan can become a nation where people of all genders have the same rights in practice—and not just on paper.

Japan often comes under fire on the world stage when discussing women’s rights. The nation came in 110th place of 149 countries on the 2018 World Economic Forum Global Gender Gap Report. The 2019 Humans Rights Watch reporton Japan wasn’t much better, citing the Tokyo Medical University scandal, poor treatment of victims of sexual violence, and lack of non-discrimination laws regarding sexual orientation and gender identity as things Japan could improve upon.

The women of Japan seem to agree that the current state of legislation is lacking. Organizations like Voice Up Japan, movements like #KuToo, and individuals like Shiori Itoare raising their voices against gender inequalityand demanding change. And their influence is having an impact.

We decided to look at legislation that could be holding modern Japanese women back to further shed light on gender inequality in Japan. If you read our article on laws benefiting women in Japan, you may notice there’s a tiny bit of overlap here. This is because laws often have multiple clauses, some which are positive and others … not so much.

Without further ado, here are four laws we believe need to be updated to better the lives of women in Japan.

1. Spouses are required to share the same surname (1896)

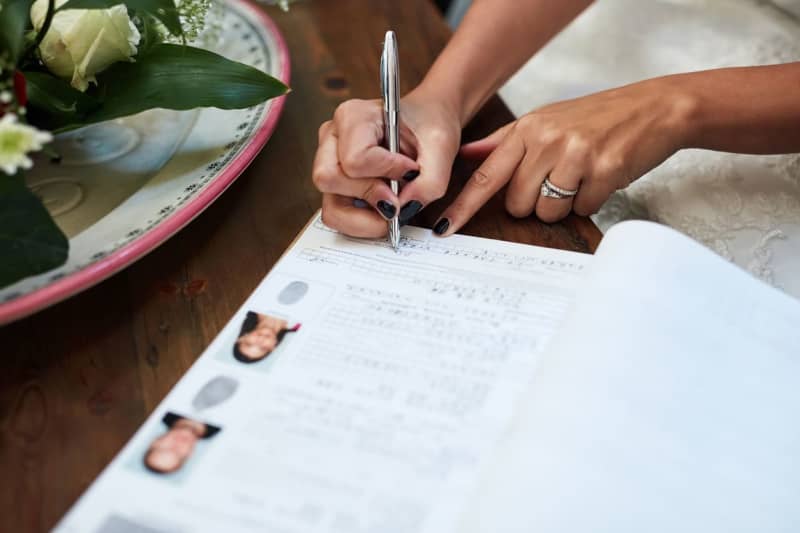

According to Article 750 of the Japanese Civil Code, spouses must share the same surname.

While the law is completely gender-neutral and in theory there’s no specification who in the relationship has to take their partner’s last name, the reality is skewed.

The problem

Thanks to Japan’s patriarchal expectations, women overwhelmingly take their husband’s last name. In fact, according to an articlefrom Nippon.com, 96 percent of Japanese wives changed their name after marriage.

The issue was brought to court in both 2015 and 2018 citing the inconvenience and distress caused by being forced to take a new name after marriage.

… 96 percent of Japanese wives changed their name after marriage.

The plaintiffs in the 2018 case (led by a man who took his wife’s surname) claimed the law was discriminatory—according to the Family Register Act of 1947, people in marriages between immigrants and Japanese nationals areallowed to have different surnames. So why not Japanese couples?

Unfortunately, the courts upheld the law both times. For now, Japanese couples still have to decide who gets to sacrifice a piece of their identity if they want to legally register their marriage. There’s a power in naming and the words we use to define who we are—a power that 96 percent of women here are forced to renounce if they want to be legitimately married.

The solution

This one is simple—the law shouldn’t force spouses to have the same surname! The public seems to agree—a 2018 Cabinet Office poll revealed 42.5 percent of respondents aged 18 and up supported allowing married couples to keep their own names, while only 29.3 percent were against changing the law. As the public continues to come around to this idea, it’s likely that the next time this issue goes to court the law will finally be changed.

2. A child conceived by a married woman is assumed to be her husband’s (1896)

In Japan, any child bornto a married woman is assumed to be her husband’s and any baby born within 300 days of a divorce is assumed to be the offspring of the former spouse. This law, Article 772 of the Japanese Civil Code, was established well before paternity tests existed, yet remains in effect today.

The problem

Let’s say a woman runs away from an abusive spouse, meets a new partner, and has a baby with him. The child would legally belong to her former, abusive husband if it’s born within the 300 day period. That’s 10 months where a woman is essentially not allowed to start a family with a new partner simply because she had the audacity to leave a former one.

Even if a paternity test proved the new partner to be the father, the shussho todoke(birth registration, also known as shussei todoke) would be denied if it listed the biological father’s name.

Furthermore, any man could use a shussho todoketo track down his current or former wife because the information is in the public record.

Even if a paternity test proved the new partner to be the father, the shussho todoke(birth registration, also known as shussei todoke) would be denied if it listed the biological father’s name.

For these reasons, a woman escaping an abusive marriage might decide not to register her child’s birth at all. Because unregistered children can’t get necessities like health insurance or a passport later in life, any mother in this scenario is faced with an impossible choice.

It’s hard to believe that in 2019, Japanese women and children belong to a patriarchaccording to the koseki(family register) system, but that’s how it remains.

The solution

The family registry system should be updated to reflect the Japanese Constitution, which itself states in “matters pertaining to marriage and the family, laws shall be enacted from the standpoint of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes.” Children could be registered under both biological parents, for instance, or even under their own names. South Korea had a system similar to Japan’s that it replaced in 2007 with a registry system based around individuals, so it’s doable!

3. The age of consent in Japan is only 13 years of age (1907)

Though Japan’s notoriously lax stance towards child endangerment has strengthened over recent years—the possession of child abuse material was criminalized in 2014 and child pornography laws were created in 2015—there remain controversial issues involving minors.

Under Article 176 of Japan’s Penal Code, it is an offense for any person to engage in sexual intercourse with a partner aged less than 13 years of age.

The problem

That’s right, the current age of consent in Japan is 13. 13!! Compared to other nations, that’s quite low. There are only three other countries in the world that have an age of consent lower than Japan’s: the Philippines, Nigeria, and Angola.

This is such a serious problem in Japan because of the common fetishization of young girls.

This is such a serious problem in Japan because of the common fetishization of young girls. JK (joshi koseior “school girl”) services, which are like maid or hostess cafes but feature minors, are abundant and feed into this fantasy. What’s worse, Japan has no specific anti-trafficking laws in place when it comes to JK services. Recruiters for JK businesses are free to aggressively scout young women and while many of the services offered are non-sexual—customers sometimes pay for nothing more than a chat and a cuppa with a high schooler—others are.

The solution

Consent laws assume a blanket standard of emotional maturity, essentially saying that every 13-year-old understands her sexuality in the same way. Some girls do mature faster and are able to understand and put the concept of consent into practice but for those that aren’t, consent laws work to protect them from abuse and exploitation. And at 13, I’d say the majority fall into the latter category.

What’s needed is a higher age of consent as well as better education on how to give and receive consent in general. While there is nothing wrong with a little fantasy, what isproblematic is how much such desires are pandered to. Young girls are fetishized in manga (in which child pornography remains legal), advertising, and of course the JK business, which also remains perfectly legal.

4. Superficial conditions for determining sex crimes (2017)

Japan’s legal stance on sex crimes was altered for the first time in over a century in 2017. The updated law introduced much-needed edits, including a longer minimum sentence for perpetrators and an expanded definition of rape, which now allows males to claim victimhood.

In order to verify an assault was rape, Article 177 of the Penal Code states that the perpetrator must have used physical force or have threatened the victim, and there must be evidence of such. Article 178 echos this for cases where the victim was taken advantage of due to a loss of physical consciousness and was unable to resist.

The problem

Sexual assault victims are often too terrifiedto resist because fighting back could anger their attacker and make them more violent. Yet, in most cases, the reason victims don’t fight back is because the attacker is someone familiar to them—perhaps, even someone they trust(ed).

Take the recent caseof an unnamed man who repeatedly raped his own daughter from the time she was 13 to 19. Because it was unclear to the jury whether she was “incapable of resisting” he was acquitted … even though he admitted in court that he became violent when she resisted.

Sexual assault victims are often too terrified to resist because fighting back could anger their attacker and make them more violent.

This all-too simplistic law fails to acknowledge these and other complexities of sexual assault. So when they come up in court, the perpetrator often walks free.

The solution

The law and the courts need to acknowledge not only the physical but also the psychological aspects that come into play for sexual abuse cases. Superficial assessment criteria have to be replaced with guidelines that take into account varying complexities. Stop victim-blaming and believe people when they say they were attacked. Easier said than done, but as women and other victims continue to come forward with their stories, the dialogue will have to eventually shift. It won’t be a simple process, but change will happen if people keep talking about why it needs to.

When societies hold back one group of people everyone is at a disadvantage. If any nation, Japan or otherwise, wants to be a place where all people can thrive not only do outdated laws have to be amended, but people’s attitudes as well.