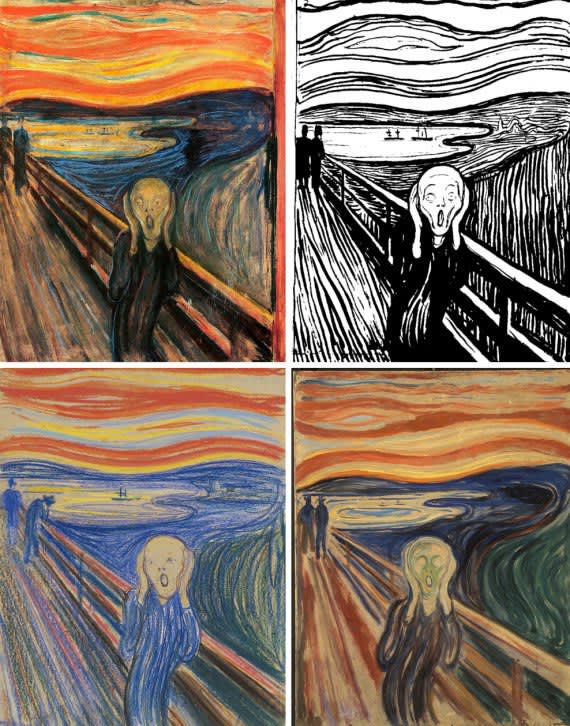

We all know Edvard Munch from that unforgettable painting where an insane man, on the verge of a breakdown, appears to scream as he stands between the red sunset and a bridge that dissolves next to him. The Screamis an overbearing image that shows Munch’s contained distress, as well as that of most of the nineteenth century’s Expressionists.

Who was this artist? And what led him to paint scenarios of such agony? It wasn’t just a movement, but an ache that seeps through the canvases, a suffering he carried since childhood that he was never able to let go. Born in 1863, he is considered Norway’s most famous artist. The calmness in his work does not come from tranquility, but from the suspense of the past or impending doom of the characters.

Each of these works is based on his sorrows and obsessions. He lost his mother, brother, and sister during his childhood, while another sister suffered from mental illness. Edvard himself was victim to irreparable anguish. Throughout his life, he endured anxiety, panic attacks, bronchitis, and alcoholism. He was witness of two world wars and was deemed a degenerate by the Third Reich.

Illness, misery, and death are always shown in his paintings. He was accused of misogyny for representing women as threatening, seductive, and leading unsuspecting men to their destruction. They weren’t just portraits of reality, but each showed a slice of the human psyche.

Related

artPainful Love Explained In 6 Works Of Art By Edvard Munch

“From the moment of my birth, the angels of anxiety, worry, and death stood at my side, followed me out when I played, followed me in the sun of springtime and in the glories of summer. They stood at my side in the evening when I closed my eyes, and intimidated me with death, hell, and eternal damnation. And I would often wake up at night and stare widely into the room: Am I in Hell?”

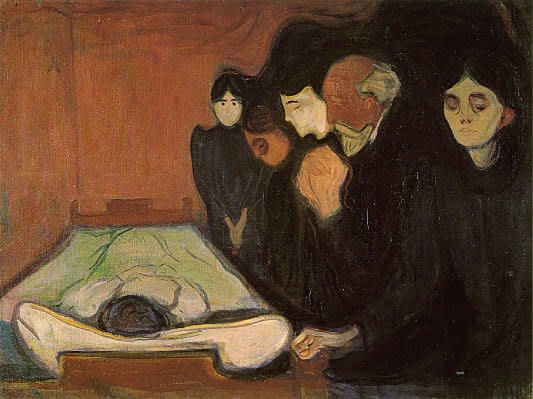

Death

“When I was born they were quick to baptize me, for they thought I’d die.”

Death in the Sickroom (1895)

Death helped Munch express the violence of a rotting body. The thick impastos make the color slide down the canvas, giving the spectator a sordid and nonchalant impression. Candlelight only illuminates the sadness in the pale faces and black clothing of the mourners. A woman gazes directly out to the person looking at the painting. Munch warns: sooner or later death will come for all of us. Munch once wrote “I live with death” in his journal and reflected that sense in all of his works.

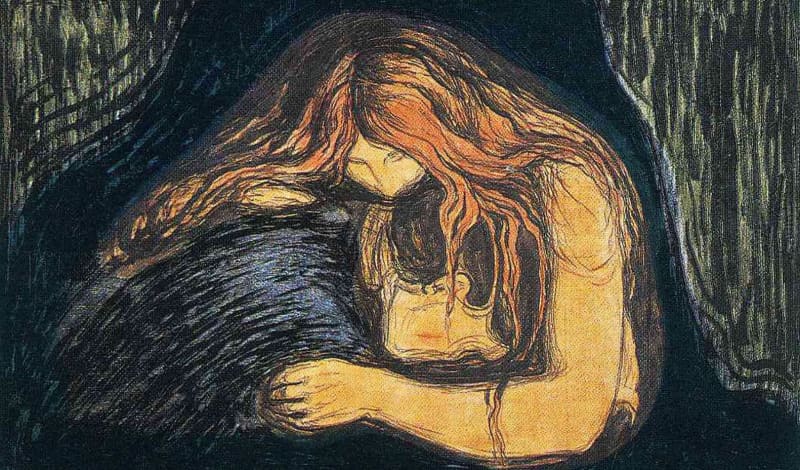

Women

Madonna (1895)

The playwright August Strindberg, a friend of Munch, described him as a misogynist that used his relationship with women to express hostile, selfish, and violent faces on feminine figures. Munch classifies women into three types: the damsel, recognized by her perfection and chastity, even sometimes by a white dress; the mistress, embodiment of sex and evil, with her long red hair ready to make men fall into her trap; and the older, loveless, widow who is always dressed in black. The painter stated: “And so it was the women who tempted and seduced the man, only to betray him after.”

Related

moviesVan Gogh In 'A Clockwork Orange'? Here Are 15 Paintings That Inspired Great Films

Murder

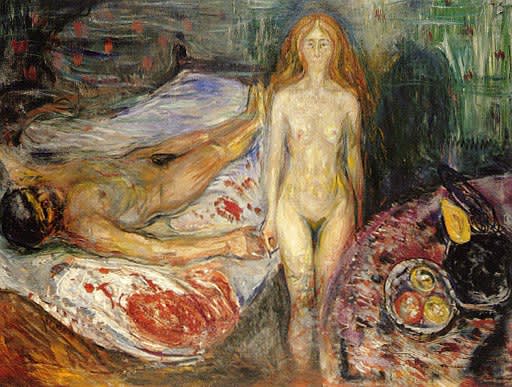

The Death of Marat (1907)

Munch’s symbols are so evident that it’s hard not to see that there is something more intense than just a scene depicting the death of the French Revolutionary leader. To Munch, the death of Marat does not mean the same thing as it does to Jacques-Louis David. It’s not depicting the politically historic moment of Charlotte Corday murdering Marat. Instead, we are clearly given the timeless story of a man betrayed by a woman. This is the more intense version based on the two paintings of the same subject. Marat’s lifeless body and his blood seep into the coverlet, as Charlotte, cold and expressionless, stares straight at the spectator. Her hair is red, the color of the temptress leading the man to his end.

Panic

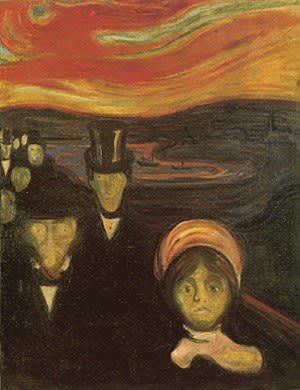

Anxiety (1894)

This canvas appears to share something in common with The Scream. The painter assured he never made copies of his works. However, he would use the same motifs to go deeper into a subject. In 1892, Munch wrote in his journal: “I was walking along a road one evening –on one side lay the city, and below me was the fjord. The sun went down –the clouds were stained red, as if with blood. I felt as though the whole of nature was screaming –it seemed as though I could hear a scream. I painted that picture, painting the clouds like real blood. The colors screamed.”

Related

art100 Of The Most Amazing Paintings In History You Must See In Person

The Cycle of Life

Dance of Life (1899)

This painting appears to be entirely symbolic due to the colors on the canvas. A young woman is depicted in white, without a partner. The one in red has seduced a man while the older one, a widow in black, waits for death by herself. The painting is a tribute to his first love, Tulla. Several couples dance in the background while at the center of the painting we see Edvard and Tulla, flanked by a young and older version of Tulla. She’s so charming that Edvard is tempted into complete surrender.

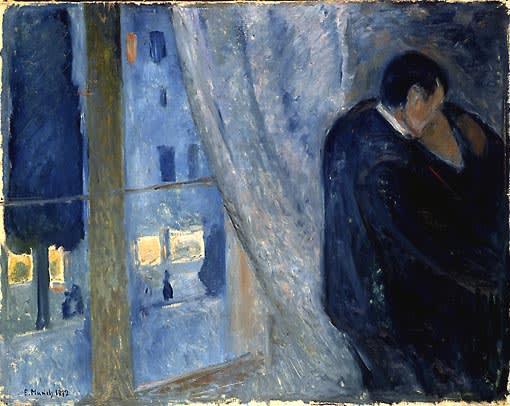

Love

The Kiss (1897)

The three versions ofThe Kissare Edvard Munch’s most unintentionally erotic pieces. Two bodies, entwined by colors in a frenzied kiss, hold on to each other. They are no longer two different people, dissolving into a black mass of shadows that surround them. Neither one has an identity, because they have turned into one entity. What Munch’s first biographer said of this painting was “We perceive two sister shapes whose faces have melded into one. It’s not possible to recognize any particular feature. All we see is the place where the fusion has occurred: it has the shape of a colossal ear that has been made deaf with the pulsing of blood, only to become a puddle of liquid flesh.”

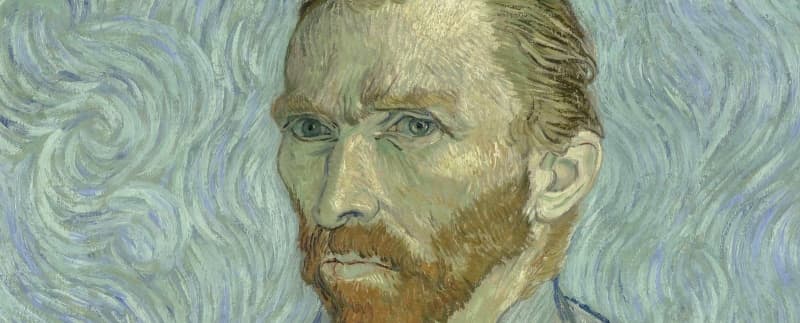

Himself

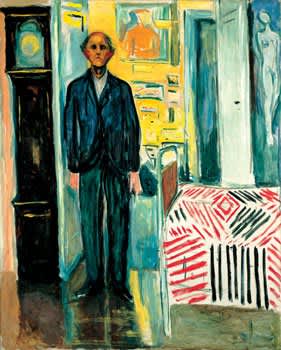

Self-Portrait: Between the Clock and the Bed (1942)

The artist’s technique evolved through his self-portraits. In 1930, at the age of 66, he suffered a hemorrhage in his right eye, making his vision into a mixture of shadows, dots, and spots. Munch feared blindness as much as he did death. This painting framed by a handless clock and his bed, Munch sees death fast approaching. He remains standing as an elongated figure with empty eye sockets.

Read more: