There are some bright spots in the budget but the Centre must make substantial strategic investments in the health system, or else, innovative initiatives like Ayushman Bharat will end up as a missed opportunity explains Oommen C. Kurian.

By Oommen C. Kurian

Perhaps for the first time in the history of India’s health policymaking, multiple agencies are moving in a closely coordinated manner, towards common policy goals. We see an unprecedented expansion of government medical colleges across the country, particularly in districts where none existed. A centrally sponsored scheme for the establishment of new government medical colleges is upgrading 157 existing district hospitals across India’s most underserved areas.

As a result, there has been a 47% rise in the number of government medical colleges between 2014 and 19, compared to a 33% increase in the total number of medical colleges in the past five years, from 404 to 539. The number of undergraduate medical seats has seen a jump of 48%, from 54,348 in 2014-15 to 80,312 in the academic year 2019-20. Government is aggressively trying to expand medical seats leveraging the private sector as well, with an aim to overcome bottlenecks in terms of personnel as well as healthcare delivery.

The High-Level Group on the Health Sector constituted by the government submitted its recommendation to the Fifteenth Finance Commission that in the coming five years, 3000 to 5000 hospitals (200 beds) needs to be created across the country.

Simultaneously, the Niti Aayog came out with a draft blueprint of a scheme to link new and/or existing private medical colleges with functional district hospitals, to augment government capacity in the sector. The High-Level Group of the Finance Commission recommended that health be shifted from the State List to the Concurrent List, and that right to health may be declared as a fundamental right on the 75th Independence Day of India in the year 2021.

These are in line with the recommendations within the National Health Policy 2017. In view of these interlinked developments, this budget was expected to plough in fresh resources into the health system, and complement its programmatic and technical leadership in the sector with matching resources as well. Despite its high visibility, the Centre spends only about one-third of the total government expenditure: states spend the remaining two-thirds. It is very clear that if health needs to shift to the Concurrent List, the Centre needs to show initiative in terms of new funds.

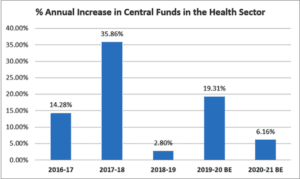

According to the latest data, the shortfall of Primary Health Centres in Jharkhand and West Bengal is at 69% and 58% respectively. The shortfall of CHCs (Community Health Centres) in Bihar is to the extent of 81%. It is calculated by the Ministry of Health that strengthening of primary and secondary healthcare delivery system as per 2011 population norms will cost INR 219,000 Crores. However, this year’s budget does nothing to sustain the promising momentum the previous budget had set forth, with around 18% year-on-year increase in allocation, despite an on-going fiscal squeeze similar to this year. This year’s allocations for health are just 6% more than last year’s. Disappointingly, money for the Department of Health and Family Welfare, which runs the healthcare delivery system, saw a paltry increase of 3.5%.

######

(Source: Budget Documents)

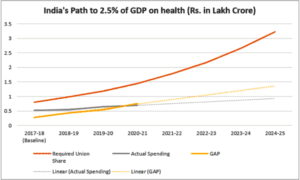

When the National Health Policy 2017 envisaged reaching 2.5% of GDP worth of government expenditure in health by 2025, it was anticipated to be an ambitious target. What was not anticipated is the spectacular way in which we failed to take that roadmap seriously. Come 2025, if remedial measures are not taken urgently, 2020-21 will have the ignominy of being the year when the gap in Central funding needed to reach the 2025 target got greater than the actual annual Central funding to health itself.

######

(Source: Fifteenth Finance Commission and Budget Documents)

As the Economic Survey argued, the current environment for international trade presents India an unprecedented opportunity to chart a China-like, labour-intensive export trajectory and thereby create unparalleled job opportunities for our burgeoning youth. Health being a major pillar of human capital, it was expected that this strategy will see substantial investments in the sector. Given the currently high vacancy positions and infrastructure gaps, strategic investments could also have promoted health as a source of decent work and helped in any effort to revive overall demand. With gross tax revenue receipts Rs 3 trillion lower than projected in the previous budget estimates, perhaps there are limits to being overly optimistic about the 2025 targets for the health sector.

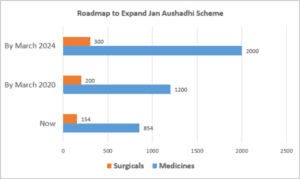

However, there are certainly bright spots in the budget. In a low cost, but high-impact venture, the government is also silently expanding the network of Jan Aushadhi Kendras across the country. The Finance Minister increased allocations to Jan Aushadhi scheme by 19% and proposed to expand it to all districts offering 2000 medicines and 300 surgical by 2024. Despite resistance from certain quarters within private industry, this scheme has seen rapid and aggressive expansion across the country. The government estimates that in 2018-19, with total sales of INR 315.70 Crore, Jan Aushadhi led to savings of approximately INR 2000 Crores. The geographical coverage of Jan Aushadhi is already impressive, with 6072 kendras covering 696 districts out of 728 districts of the country.

######

(Source: Budget Documents and Lok Sabha Question)

Equally promising is the considerable budgetary attention Pardhan Mantri Swasthya Suraksha Yojana (PMSSY) has received. The scheme spearheads the expansion of government infrastructure in medical education and healthcare delivery in the most hard-to-reach areas in the country. The latest budget saw its allocations go up considerably from INR 4000 Cr (2019 BE) to INR 6020 Cr (2020 BE), an impressive 51% jump in a contractionary budget.

Many prestigious institutions like All Indian Institute of Medical Science saw allocations decline in the budget. Many of these are empanelled in PMJAY and some experts think it is a move to avoid “double billing”. If that is the case, it will be a way of dis-incentivising the fund starved institutions who compete with private empanelled hospitals to earn PMJAY money which should ideally be spent on local needs. However, an embarrassing error by the Ministry of Finance hints at the fact that many allocations to institutions like Safdarjung Hospital, Vardhman Mahavir Medical College, and All Indian Institute of Medical Science, New Delhi itself, saw last-minute upward revisions. This gives hope that health still has high-level policy attention and more funds will be released over the course of the year as needs arise.

A year when allocations to National Health Mission saw stagnation, the move to offer Viability Gap Funding to set up hospitals and upgrade district hospitals to medical colleges in the PPP mode was perhaps the most controversial. It is suggested that “those states that fully allow the facilities of the hospital to the medical college and wish to provide land at a concession, would be able to receive Viability Gap Funding”. It is clear that the idea is to complement a strong expansion of government capacity by leaning on the private sector. However, setting up PPPs in underserved areas where government capacity to monitor and regulate is very low or non-existent needs to be informed by failure of similar experiences of the past in major megacities – supposedly among the better-governed parts of the country.

There will be pushback to such PPPs from multiple stakeholders, and these projects may take time to take off. Proceeds from the new health cess on import of medical devices (estimated to yield around INR 2000 Crore), proposed in the budget to support PPPs should instead be used initially to ramp up Health and Wellness Centres (HWC) in aspirational districts. Judging by the severe downward revision of funds to the PMJAY arm, and slow physical progress despite very high utilization of funds within the HWC arm, it may be useful to focus on strengthening comprehensive primary health care on the ground, rather than spend money on uncertain projects. It is also a matter of great concern that this year’s budget has cut down by 22% the allocation to the statutory and regulatory bodies within health, despite new PPPs being proposed which will need regulatory oversight.

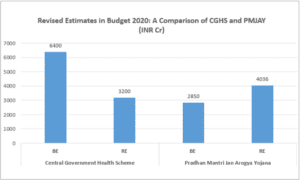

However, the primary cause of concern remains the performance of government’s flagship scheme, Ayushman Bharat and especially the PMJAY arm, launched to challenge the status quo in the healthcare delivery system, where for most, quality healthcare has remained a luxury good. The slow uptake of PMJAY due to up to 30 per cent of the eligible beneficiaries being untraceable, lack of awareness among the target population, as well as centre-state tussles delaying payments are affecting the implementation. It was reported last month that INR 500 crore from PMJAY’s original kitty of INR 6,400 crore was reallocated to the Central Government Health Scheme (CGHS), a scheme that caters to civil servants of “all four pillars of democratic set up in India namely Legislature, Judiciary, Executive and Press”. Budget 2020 estimates show that while PMJAY allocations were revised downward by half, CGHS allocations were revised upwards considerably, by about 42%. To put things in perspective, a scheme offering healthcare coverage to just around 35 lakh CGHS members are allocated INR 836 Cr more than a scheme which caters to 50 crore people.

######

(Source: Budget Documents)

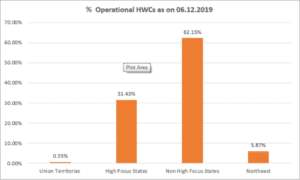

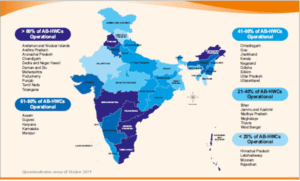

A look at the status of up-gradation of HWCs shows that the pace is slower than planned, and a high number of functional HWCs are concentrated in the relatively better-off states. High Focus States, consisting of Bihar, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand who together account for around half of India’s population have only 31% of the functioning HWCs in the country.

######

(Source: Rajya Sabha Questions)

Recent research by the Accountability Initiative has shown that the proportion of functioning facilities that met IPHS norms has been declining steadily over the last three years. As of March 2018, there were only 7 per cent SCs, 12 per cent PHCs, and 13 per cent CHCs functioning as per IPHS norms. As HWCs expand, which by definition fulfil IPHS norms, the situation is bound to improve. However, the slow progress calls for increased focus on NHM in general, and HWCs in particular. Slowly, a new disparity is emerging across the country, whereby comprehensive primary health care is being deployed effectively and quickly across the better-off states, particularly down south, and the rest of India is being told to wait. This needs to be remedied and remedied urgently.

The proportion of Operational HWC’s the Across States

######

(Source: https://ab-hwc.nhp.gov.in/)

In short, no, Budget 2020 does not provide material support for the ongoing health reforms. Unless the Centre commits additional resources to health and the Centre-State relations are streamlined offering more flexibility to the States to contribute meaningfully to Centre-led initiatives, the sector will remain within a more-of-the-same trap forever, despite minor increases in allocations. Facilitating a smooth transition to health becoming a Concurrent subject, the Centre must make substantial strategic investments in the health system, or else, innovative initiatives like Ayushman Bharat will end up as a missed opportunity.

(This was first published at ORFand is being republished here with due permission.)

(Oommen C. Kurian is a Senior Fellow & Head of Health Initiative at ORF working on public health. The views expressed above belong to the author.)