SAN DIEGO: In the 1770s, neither White nor Black American patriots could buy or make an American Revolution. Their spirits ‘became’ the revolution. Early patriot stories are troves of knowledge – even national treasures. Since then generations of patriots have protected the self-governing, free republic they created. Sadly, there are Americans in news today that appear to hold no value to America or her history, including the Revolution. The story begins with the black patriot, Crispus Attucks, the first casualty the American Revolution at the hands of the British soldiers.

On this July 4th, the past 244 years tell us where we went wrong and what we did right – and how far we’ve come. It also proves America’s Independence from Britain was the fight of both black and white patriots.

Black Americans played a unique role in America’s early fight for independence. For 150 years, the colonists had experienced an unusual amount of freedom managing their own affairs. Yet the British umbrella hung over the colonists – taxing, controlling, and manipulating trade for King George III’s gain.

Continuing offenses fomented a rebel movement.

In 1774, British Parliament passed the Boston Port Act.

This closed the port of Boston and a demand was made to pay for the nearly $1 million worth (in today’s money) of tea dumped into the harbor.

The 1773 Boston Tea Party was a political protest for imposing “taxation without representation.”

The colonists risked all.

These people were farmers, businessmen that stepped on a ledge to protect their families and livelihoods against British usurpation. As well as to secure rights, liberties, and opportunities of which the world had never seen. It is well-known slavery existed in those early days, yet Black American patriots stood alongside their White counterparts ‘to be the revolution’.

Jamestown & Yorktown: Remembering the women and black soldiers who founded America

Today, their stories matter more than ever as we see markers, monuments, names, and mentions being removed from America’s cities in futile attempts to erase a past. One that tells America’s entire story.

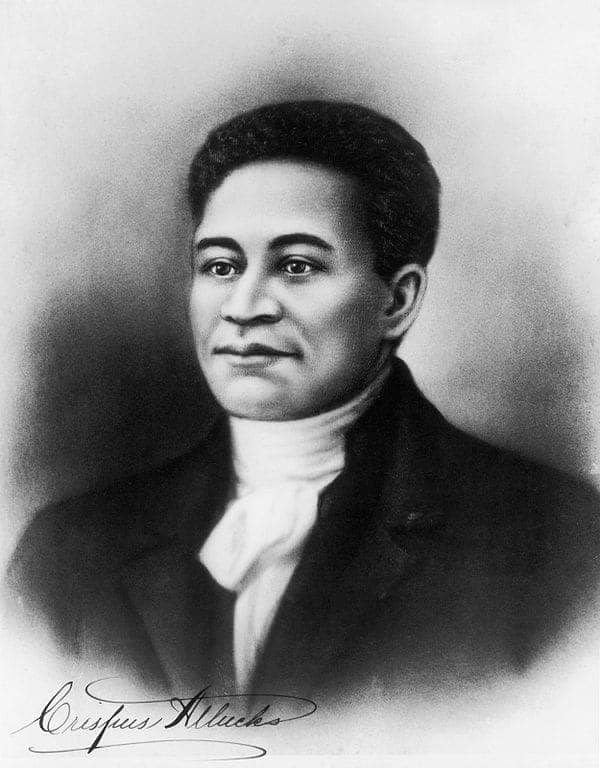

Crispus Attucks: The first African American casualty of the American Revolution.

Summarized from History.com,

Born in 1723, little is known about Crispus Attucks, except that he was first to fall during the Boston Massacre, March 5, 1770. This street riot put a spur to the American Revolution. It is believed Attucks was the son of Prince Yonger (a slave from Africa) and Nancy Attucks, a Natick Indian, born in the vicinity of Framingham, Massachusetts. Having escaped slavery at age 27, he worked on whaling ships (one of the few trades open to non-whites). When not at sea, this mariner found work as a rope-maker.

Crispus Attucks. Artist unknown, Creative Commons public domain https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:public_domain

Author Douglas R. Egerton writes in eath or Liberty: African Americans and Revolutionary Americathat the British paid their soldiers poorly. This resulted in an influx of troops to get part-time off-duty jobs. Jobs that New England sailors and rope-makers needed. Attucks was also at risk to be pressed into British naval service, his skills as experienced seaman put to work for a king not his own.

Tensions ran high in Boston when 2,000 British soldiers occupied the city of 16,000. There to enforce Britain’s rule.

Al Goodwyn Cartoon: Celebrating a Capitol 4th – Schedules, livestreams

Boston Massacre: The spark that grew into a lethal flame.

From History.com,

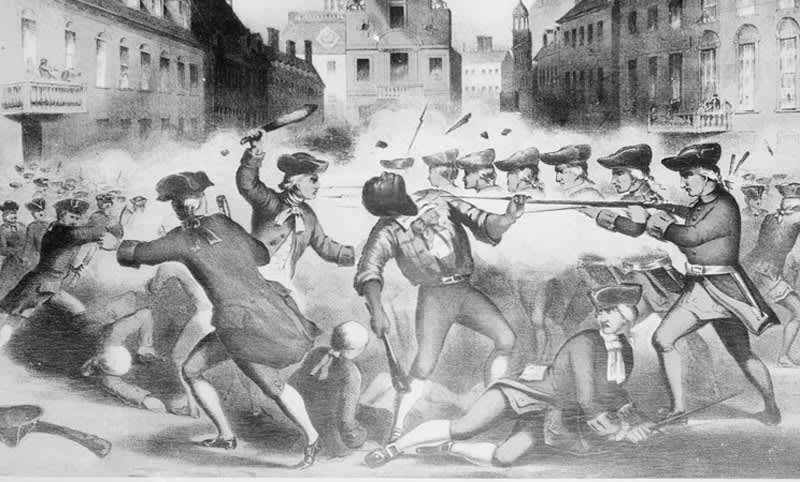

“On the frigid, snowy evening of March 5, Private Hugh White was the only soldier guarding the King’s money stored inside the Custom House on King Street. It wasn’t long before angry colonists joined him and insulted him and threatened violence.”

“At some point, White fought back and struck a colonist with his bayonet. In retaliation, the colonists pelted him with snowballs, ice and stones. Bells started ringing throughout the town—usually a warning of fire—sending a mass of male colonists into the streets,” writes History.com

White fell under the assault and called for help. In response to White, and fearing mass riots and the loss of the King’s money, Captain Thomas Preston and several soldiers took up a defensive position in front of the Custom House.

The gathered colonists (about 200) threw ice chunks, stones, and sticks at the squad of British soldiers with rifles.

A sailor/rope-maker worried about his job.

Attucks was reported to be at the front of the angry group that confronted the British soldiers His defiance took courage when a man escaped from slavery might have backed away. He joined the others in a united fight to survive.

Multiple testimonies from original trial transcripts say the colonists (mostly sailors) swung rope-making sticks at the soldiers, hitting them and knocking guns away. No one wants a gun in their face.

Summarized from History.com,

One witness, an enslaved man named Andrew, said Attucks (a stout man referred to in the trial records as a mulatto) swung a stick or club at Capt. Thomas Preston. Then knocked away a soldier’s gun and hit him (Hugh Montgomery) in the face or head. Attucks grabbed the soldier’s bayonet in the other hand and taunted with the crowd moments before Montgomery gained control of his gun.

“Fire, damn your blood, fire,” was heard, according to testimony from bookstore owner, Henry Knox (one of Washington’s future generals). The word “Fire” was reported to be on the lips of the crowd, but no one knew who.

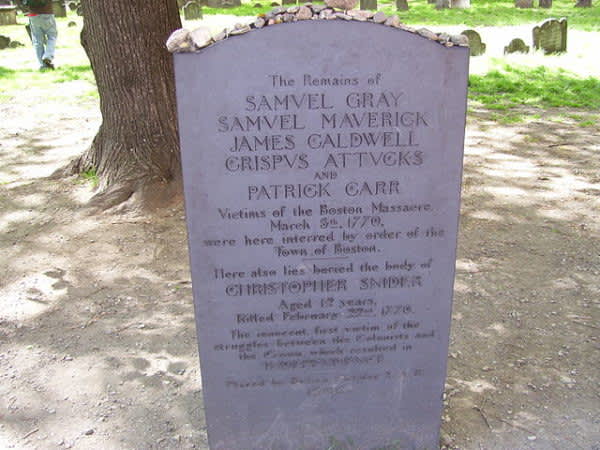

Attucks was struck twice in the chest. Samuel Gray, also a rope-maker, was shot in the head. Both died, along with three others.

BOSTON, 1770. Engraving and etching created by Paul Revere Jr. (not historically correct according to trial testimonies) Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910. Source https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/365208 https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en

Who actually said “Fire”?

Summarized from History.com,

Preston and his men were arrested and jailed, while Sons of Liberty leaders such as Samuel Adams and John Hancock fueled the propaganda machine to keep the colonists fighting the British. It took seven months to bring them to trial; Attorney John Adams (future president of the U.S.) took the case.

“Adams was no fan of the British but wanted Preston and his men to receive a fair trial,” writes history.com.

The death penalty and possible British retribution loomed. Adams convinced the judge to seat a jury of non-Bostonians. Using Richard Palme’s eyewitness account, Adams argued that reasonable doubt existed that Preston had ordered his men to fire on Attucks and the angry colonists. And that Preston was standing in front of his men, not behind as some testified.

Adams proved the claim of self-defense for the rest of the soldiers to win the verdict ‘not guilty’. Hugh Montgomery and Mathew Kilroy charged with manslaughter. And as first offenders, per British law, were merely branded on the thumbs.

More than half of Boston’s population carried the caskets of the slain patriots to the graveyard. Attucks was buried with the others despite segregation and received honors uncommon for a Black American.

MASSACHUSETTS, 1770. Boston Massacre victims grave including Crispus Attucks in Boston Massachusetts’ Granary Burying Ground. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

Peter Salem: He who shot a British commander at Bunker Hill.

Summarized from Revolutionary War Journal:

1770s. Peter Salem by artist Walter J. Williams, Jr. (Date unknown). Source: http://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/peter-salem/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain

Peter Salem was also born in Framingham, Mass. (1750). Jeremiah Belknap, an army captain, was his owner. It is believed he was sold to Major Lawson Buckminster at the age of five.Since 1656, African Americans were legally barred from serving in the militias, due to fear of slave insurrections. Buckminster freed Salem to enlist in his regiment.

He became part of Captain Simon Edgel’s company of ‘minutemen’ – prepared for action at a moment’s notice (early military crisis response).

In the battles of Concord and Lexington, Salem fought alongside his former masters. He gained the most notoriety during the Battle of Bunker Hill, June 1775. As part of the Fifth Massachusetts Regiment led by Col. John Nixon, Salem, and rebel troops were positioned in a redoubt. They were eventually overrun by the Redcoats, led by Major John Pitcairn – a very important British leader during the American Revolution.

A fatal battle moment brings praise.

Aaron White of Thompson, Connecticut, recorded the following, based on an eyewitness account:

*The British Major Pitcairin had passed the storm of our fire and had mounted the redoubt, when waving his sword, he commanded in a loud voice, the rebels to surrender. His sudden appearance and his commanding air at first startled the men immediately below him. They neither answered or fired, probably not being exactly certain what was to be done. At this critical moment, a negro soldier stepped forward and, aiming his musket at the major’s bosom, blew him through.*

“Salem’s superiors later introduced him to General George Washington as “the man who shot Pitcairn,” says revolutionarywarjournal.com.

The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Artist John Trumbull had enlisted in the provincial army, and was at Roxbury during the battle. He had interviewed many of the participants from this important event. Peter Salem is believed to be represented in Trumbull’s painting. Salem is at the far right, observing the carnage, and the death of General Warren. From the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, accession #1977.853: http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/the-death-of-general-warren-at-the-battle-of-bunker-s-hill-17-june-1775-34260 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain

American patriot of the hour short-lived.

Salem’s lone heroic act did not stop General George Washington, a southern planter with fear of slave insurrections, from issuing an order Nov. 12, 1775, barring African Americans from military service.

Salem returned home.

Five days previous, Lord Dunmore, Royal Governor of Virginia, freed all slaves of patriots willing to serve the British. When Washington got word, he canceled the old and issued a new order on Dec. 30th. One that permitted free African Americans to serve.

Our extraordinary Declaration of Independence still protecting freedom

Salem reenlisted and joined the Northern Army to fight General Burgoyne. Who tried to cut off New England from the southern colonies.

Discharged from the army in 1780, Salem remained a Framingham militiaman until the end of the war. He was favored among the community yet destitute and died August 16, 1816 in the poorhouse.

His burial among whites again – a considerable honor. A monument to him was erected at the Old Burying Ground.

James Armistead Lafayette – American Revolution Spy.

Summarized from Battlefields, Wikipedia,

In 1760 – James Armistead came into the world as a slave on a Virginia plantation and lived most his young life there. When the American Revolution ramped up, his master William Armistead gave him permission to enlist. He joined the Marquis de Lafayette’s French Allied units.

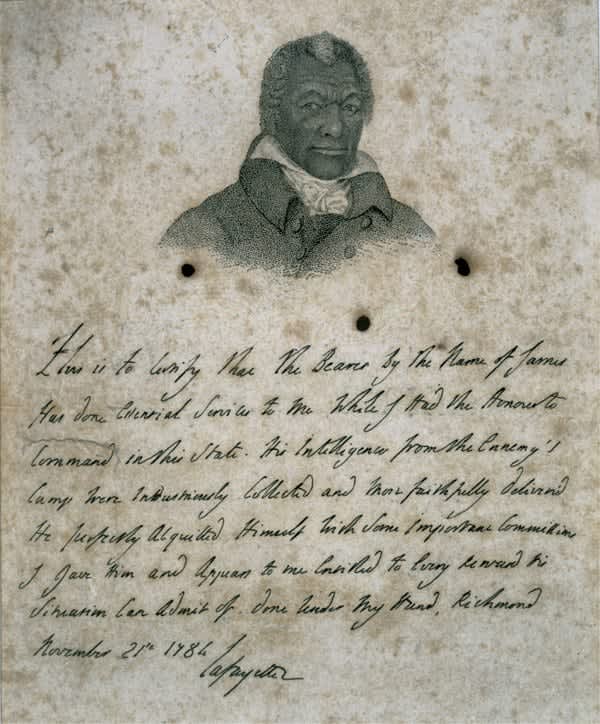

Facsimile of the Marquis de Lafayette’s original certificate commending James Armistead Lafayette’s service on behalf of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Marquis de Lafayette – Virginia Historical Society image from the Library of Virginia website https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain

He became a spy acting as a runaway slave to get access to British General Cornwallis’ headquarters. He knew Virginia terrain as a native becoming an asset to the unsuspecting British.

To be at the center of the British War Department was an accomplishment few spies could hope for.

Leading a double agent’s life, Armistead went from friendly camp to enemy camp. To Lafayette, he relayed vital intelligence and to the enemy – misleading information. He eventually was assigned to notorious turncoat Benedict Arnold.

Pretending to be a spy Armistead gained Arnold’s confidence enough to guide British troops through local roads.

Armistead joined Lord Charles Cornwallis after Arnold departed north spring of 1781. He heard officers speak openly about battle strategies in front of him as he frequently moved from camp to camp. Armistead documented his intelligence in reports that he delivered to other American spies.

A Black American patriot spy’s finest acts.

The Battle of Yorktown was a critical turning point in the American Revolution. Armistead provided instrumental espionage to both Lafayette and Washington about British reinforcements approaching. This gave time to impede the enemy with blockades.

The surrender by Lord Cornwallis on Oct 17, 1781, became the final major victory for the colonists. American independence finally won after years of hardship and struggle.

Surrender of Lord Cornwallis, Battle of Yorktown, Oct 17, 1781. Artist John Trumbull (1756-1843). This painting depicts the forces of British Major General Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis (1738–1805) (who was not himself present at the surrender), surrendering to French and American forces after the Siege of Yorktown (September 28 – October 19, 1781) during the American Revolutionary War. The central figures depicted are Generals Charles O’Hara and Benjamin Lincoln. The United States government commissioned Trumbull to paint patriotic paintings, including this piece, for them in 1817, paying for the piece in 1820. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain

George Washington and the freedom of his slaves

Unfortunately, Armistead’s status as a spy gave him no benefit from the Act of 1783 that emancipated slave-soldiers of the Revolution. He was a spy, not a soldier.

Though in 1786, James petitioned for his freedom with the help of William Armistead (then a member of the House of Delegates) and a 1784 testimonial given by Lafayette himself. On January 9, 1787, the Virginia Assembly granted the petition. At that time, he added “Lafayette” to his name to honor the general.

With an annual pension in hand – he moved to his own 40-acre Virginia farm and lived out his remaining life free – with his family. He died in 1832 a wealthy man.

History matters.

In the rush to tear the past apart or delete it – rising generations of Americans miss out on the whole story of America. Each a building block of this nation.

Civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote in 1964 that black schoolchildren know:

“The first American to shed blood in the revolution that freed his country from British oppression was a black seaman named Crispus Attucks.”

Attucks, Salem, and Armistead plus countless other American patriots ‘were the American Revolution.’ They put their lives on the line for something they believed in and left it in our hands. They fought for the land that today’s mobsters and anarchists are trying to destroy.

It may be that some history needs to be taught, because to America, their Black Lives Matter.

Thankfully, you can never take the spirit of a true patriot away. It lives on.

God Bless America and Happy Birthday this July 4th!

Be informed and learn more about Slavery in the colonial United States

Featured Image: A 19th-century lithograph variation of Paul Revere's famous engraving of the Boston Massacre. Produced before the American Civil War, this image emphasized Crispus Attucks in the center. He became an important symbol to abolitionists of sacrifice and black freedom. (By John Bufford after William L. Champey, circa 1856)[4] Image by Unknown author or not provided - U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15894803