While the rest of Australia opens up, Melbourne is back under lockdown, battling uncertainties over growing community transmission risks. The ongoing six-week lockdown, within a month of the country coming out of the first one, is estimated to have severe economic repercussions.

By Dayawanti Punj

After cases peaked towards the end of March, with a 24-hour record high of 469 cases being reported on March 28, the COVID-19 curve in Australia saw a steady decline. Most of the cases at the time were concentrated in New South Wales, where the national capital, Sydney, is located. However, since mid-June, the coronavirus curve has been on the rise again. This time, the south-eastern state of Victoria, particularly metropolitan Melbourne, accounts for the lion’s share of the outbreak.

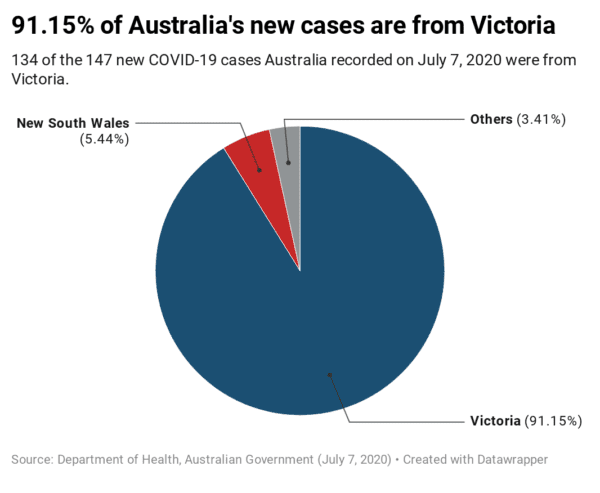

On July 7, Victoria recorded the highest number of COVID-19 cases, prompting the implementation of Stage 3 ‘Stay at Home’ restrictions on metropolitan Melbourne and Mitchell Shire for a period of six weeks, starting July 9. The rest of the state is under ‘Stay Safe’ restrictions.

The lockdown, announced within a month of the country coming out of the first one, is likely to have severe economic repercussions. The state of Victoria is cut-off from the rest of the country: severing trade and commerce links for an extended period of time. An especially impactful regulation is the closure of borders between Victoria and New South Wales, as this will block the route from Melbourne to Sydney.

Melbourne matters

COVID-19 cases in Victoria are growing more rapidly than any other state. Over 90 percent of the total new cases in Australia are from the Melbourne area: the second-largest city in the country. Out of the 772 active cases, a significant portion (15.5 percent till date) of Victoria’s cases have unknown epidemiological links.

According to a report by the Victoria State Government, 456 COVID-19 cases are suspected to be community transmission risks, which means that these patients have neither come from overseas nor have they had any known contact with a COVID-19 patient. This is particularly worrying because a higher community transmission rate could be indicative of more clusters or cases that haven’t yet been tracked down by the government.

In Melbourne, the most prominent cluster is the nine towers cluster, which consists of the public (government) residential housing buildings located in the Melbourne and Moone Valley local government areas. This cluster has received a lot of attention – from the government and the media – due to the recent harsh and restrictive lockdown on over 3,000 residents. They are prohibited from leaving their buildings for any reason other than urgent medical care for an estimated period of almost two weeks, while testing and isolation measures are carried out.

In a verbal statement released recently, the Chief Health Officer Brett Sutton outlined the reason for these drastic measures: “This particular setting has genuinely explosive potential for the spread of this virus.” Certain concerns that make this housing community disproportionately vulnerable to the spread of the virus include multiple small, overcrowded housing units, a large number of people sharing facilities like laundry rooms and elevators, and the unknown health status of many residents (mostly migrants or living on low wages). Other severely affected municipalities include Melton and Wyndham with the Al-Taqwa college cluster and Brimbank with the Albanvale primary school and Deer Park social event outbreaks.

Apart from cordoning off hotspots, the Australian Government has also extended the state-wide declaration of emergency in Victoria, first enacted on the March 16 till July 19.