In the biggest health crisis of the century, Malayali nurses find themselves at the frontlines, fighting the battle against COVID-19. But some nurses are dealing with nightmarish conditions including longer working shifts, lower salary and even treating COVID-19 patients without proper safety kits.

By Dayawanti Punj

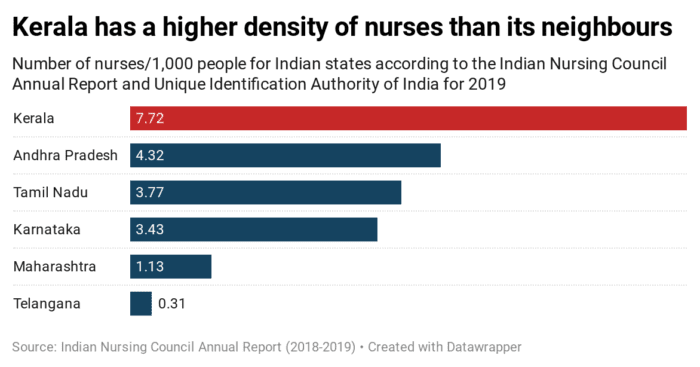

The South Indian state of Kerala is renowned for its world-class medical facilities and for producing the maximum number of registered nurses in India. And, they can be found all over the world. In fact, many of them are currently working as frontline warriors in various countries, fighting the battle against COVID-19.

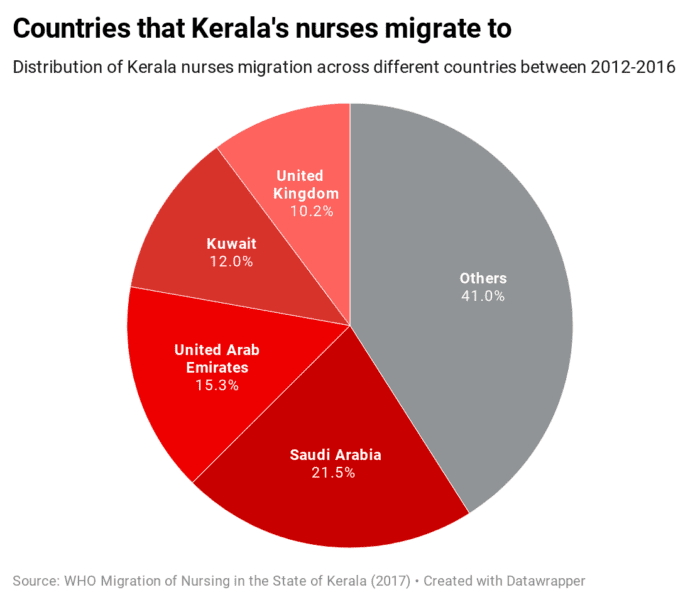

It has been reported, despite lockdown, a number of rescue flights carrying dozens of Malayali nurses were specially flown to different parts of the world to tend COVID-19 patients. “Every year around 20,000 – 25,000 nurses from Kerala choose to go and work abroad,” said Sudheep MV, national secretary of the United Nurses Association (UNA).

UNA was created by working nurses of Thrissur in 2011 and today the organisation boasts of having some 5.5 lakh members who are either working or are retired nurses in Kerala.

But since the global outbreak of coronavirus, some 1100 nurses have flown to various parts of the world. “Over the last two months, around 900 nurses have flown to the Gulf countries and some 200 to Ireland from Kochi amid COVID-19 crisis,” he informed.

According to a report published by the Nurses Council of India, of the 20 lakh registered nurses in the country, at least 15 lakh are from Kerala and the State has the capacity to train over 17,600 nurses annually. “At least two lakh of our nurses are abroad. Nurses from Kerala are most sought after,” said Sudheep.

Agrees Capt. Ajitha Nair, Chief Operating Officer, Avitis Institute of Medical Sciences, Palakkad, Kerala. “The Malayali nurse is a ubiquitous brand. Though developed countries like the US, Canada, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, and Germany have a maximum number of Malayali nurses, they choose to go to Middle East Countries as well. This is due to ease of migration and tax-free employment,” she said.

Even a WHO report noted that “nurses trained in India form a significant portion of internationally educated nurses working overseas, second to nurses trained in the Philippines. It is estimated that over 30 percent of nurses who studied in Kerala work in the UK or the US, with 15 percent in Australia and 12 percent in the Middle East.”

While hailing the services of nurses and midwives of the State, the Chief Minister of Kerala in his tweet said, “Kerala’s greatest exports to the world are love and care. Our State is one of the world’s largest contributors to the talent pool of nurses.”

Therefore, it comes as no surprise that in the biggest health crisis of the century, these nurses find themselves at the frontlines.

In the UK, former British MP Anna Soubry in a recent interview observed that “…some of the best nurses that we learn from actually, are from South India, from Kerala in particular”.

Veteran nurses say 75 percent of all Malayalis have at least one nurse in their family. While affirming the same, Capt Nair added, “Yes, Kerala produces the highest number of nurses in the world. They study nursing in almost all states of the country wherever nursing schools and colleges are situated and in aggregate its the highest in number.”

According to her though there is no particular district where the maximum number of nurses come from, however Kottayam, Ernakulam, Pathanamthitta, and Kannur tops the list.

In fact, many who fail to get admission in the State choose to opt for nursing colleges in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh.

“Despite being faced with fewer job opportunities in the home country, abysmally low wages, poor living and working conditions in our country, nurses from Kerala have thrived on a unique quality, that is their unparalleled resilience and professional commitment,” said Capt Nair.

How did Kerala end up producing so many nurses?

A lot of this is due to the influence of Christianity and the Christian Missionaries who set up some of the best hospitals in the State. They also began training girls from the community as nurses, who later migrated abroad and lived a better lifestyle.

“Whilst nursing used to be community-specific in the 60s and 70s, from the 1980s it changed from Christian dominant profession to an attractive career choice to all communities,” said Capt Nair.

The profession offered a good opportunity for many middle to low-income families in the State. It gave them hope that if at least one of them got a job in another country, the family is secured for life.

“Being Keralites they are being brought up dreaming of migration. This gives them the unique mental capability to adapt to any circumstances,” added Capt Nair.

The exodus

Keralite nurses- particularly female nurses- started finding empowerment through employment opportunities abroad which offered a better lifestyle, working conditions, and salaries. “The nurses are not just looking to make more money. Rather, it’s the combined incentives of a better lifestyle, better education for their children, and a higher standard of geriatric care that’s pushing them abroad,” said Sudheep.

Also, migration is an attraction to all working Keralaites because of the specific geographical and economic conditions in their home state.

According to Capt Nair, Kerala has the highest literacy and population density in India and thereby has the largest number of skilled and semiskilled employment seekers. “The prevailing geopolitical situation does not attract new industry and employment generation in Kerala due to lack of space and relatively high cost of workforce,” she said.

Further, as far as nurses are concerned, employment opportunities in the home state are practically far and few as there is a strong public sector health system. Hence the nurses have no choice but to seek a job elsewhere. “Being a consumerist state, unless you earn well, life is difficult,” added Capt Nair.

In its early years, young women, especially from working-class families across religions, eagerly signed up to become nurses because no specific educational qualification was required and jobs were easy to secure. However, over the years, the nursing community expanded. While it still is not a well-paying profession, it did provide these women opportunities to travel and see the world.

“Another reason for choosing foreign shores is that Malayali nurses are very ambitious and they long for a better salary and a good lifestyle. Migration allows them to send money back home besides helping other family members to migrate,” informed Sudheep.

Thus, the foreign remittance from Non-Resident Keralites ensures the enhancement of the per capita income of the State. To put this into context, Rs 85,092 crore is the amount Kerala received as remittances (March 2018), accounting for 35 percent of the state’s GDP.

“Keralite nurses by and large are willing to go to any foreign country if the pay is good,” said Capt. Nair. “Iraq and Libya offered close to a lakh monthly remuneration and nurses used to go there. However, after the evacuation two years ago, it has been stopped for now”.

Within India, a huge number of nurses migrate to Delhi, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, and Karnataka.

Furthermore, while in the past, the profession was gendered and considered a ‘woman’s profession’, incentives of greater employment opportunities and high salaries abroad have resulted in a greater proportion of men in Kerala entering the field.

“Malayali men joining nursing in large numbers started along with the turn of the century. The reason for the surge of men in nursing is undoubtedly the opportunity for migration. However, Kerala hospitals have less than 20% men nurses on an average,” informed Capt. Nair.

The plight of nurses during corona times

The current healthcare crisis has brought the plight of nurses, the first line of contact with patients to the forefront. From lower salary and longer working shifts to facing a shortage of PPE kits, nurses have faced it all.

It was on Malayali nurses’ persistent calls that Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan had to intervene and write to Maharashtra CM Uddhav Thackeray urging him to ensure the safety of nurses attending to COVID-19 patients in Mumbai and other parts of the State.

At a time when India’s health system has taken a toll, nurses are first responders in the battle—taking samples for tests, bringing patients to quarantine facilities, helping them get critical care in ICUs—risking their own lives.

Unfortunately, these dedicated warriors never get due credit; long duty hours, low salaries, and no social recognition are their lot.

Vanaja Jayaprasad, an expatriate senior staff cardiology nurse currently practicing in Dubai while sharing her experience said, “I often feel numbness all over my legs due to the vehemently busy working hours.”

She said, “Further, PPE kits make it harder to carry out essential daily activities like drinking water and using the washroom. However, it is having to wear a mask for continuous hours that poses the greatest physical challenge, often resulting in nausea and dizziness after a long day at work.”

Being a nurse in a non-COVID-19 facility also takes a toll on my mind. “It’s difficult to feel safe even in a non-COVID-19 unit, as there are cases where patients test negative one day, and positive the next,” explained Jayaprasad.

While working at a hospital in UAE, where approximately two-thirds of the nursing staff hails from Kerala, Jayaprasad, a native of Kottayam district feels that a defining quality of Malayali nurses is their knowledgeability, sincerity, and hardworking nature, which is recognised across the world.

However, Kerala, the largest exporter of trained nurses from India, has done little to improve conditions back home. If experts are to be believed the State is going to face a crunch of experienced nurses in the coming five years. “It is the government’s responsibility to create initiatives that help this hugely employable sector realise opportunities in the country,” said Sudheep.

According to him, a nursing student’s ordeal starts right from the day they seek admission to a nursing college. “Usually for a 4 years nursing course, students take an education loan. But the starting salaries in the country are so low, that forget repaying the loan, they even find it difficult to make their ends meet,” he said.

For Sudheep, a professional nurse himself, “Keralites take nursing as a holy and noble profession. They even go beyond the call of duty to serve patients.”

Perhaps the reason nurses from Kerala are so much in demand, across the globe.