The number of Indian students pursuing MBBS in China has grown immensely in the past few years. Today there are an estimated 21,000 Indian students studying MBBS in China. Now due to India-China border tension, the future of these students looks bleak, reports Nikunj Sharma.

By Nikunj Sharma

Thousands of Indian doctors who graduated from Chinese universities, foreign education consultants in India, and medicine aspirants for Chinese universities are all skeptical about their future prospects in their own country. Reason? The continuously growing anti-China sentiments since the COVID-19 outbreak coupled with India-China border stand-off is making both the domestic work environment and study scenario in the neighboring country tad complicated.

So much so that Indian students who came back from China during winter break in January are not even sure whether they will be allowed to join back their course or university in China.

While most students have a mixed reaction to the current situation — be it about their career or post-COVID travel, Nitesh Dunda, a Jaipur-based MBBS student at China’s Harbin Medical University is uncertain about his future prospects.

“My entire future and investment is on stake amid this Indo-China border issue,” said Nitish.

Dunda is among 20,000 Indian medical students who are pursuing higher education in China. He, like many others, is currently stranded in India due to the pandemic. As he waits for normalcy to prevail, he added, “I am in constant touch with the university and authorities in China, but I am a bit skeptical about things changing anytime soon.”

Dunda was hoping to graduate this June.

After COVID-19 outbreak, the border dispute came as a fresh jolt to the students who are in the middle of their courses and had plans to join back their colleges in China around September 2020.

Amid growing tension between two countries, education counselors are also reporting a sharp decline in queries related to education prospects in Chinese universities.

“The current situation with China is tense and thus, the future of students who aspired to study in China looks bleak,” said Rahul Kumar, a Delhi-based education counsellor.

China opened its education system to students from overseas in 2003, since then demand of Indian students going to study medicine in the country has only increased.

“The trend is being encouraged by fierce competition for limited medical seats in India and the expense of private medical colleges here,” said Kumar.

Every year 7,000-8,000 students from India go to China to enroll for a medical degree. While to earn a MBBS degree in China it takes 6 years and an investment of about 25 lakhs, in India, the same degree in any private medical college may cost you a whopping ₹ 40 to 75 lakhs.

Rajiv Ganjoo, founder CEO of ADMITAS, an educational consulting firm based in Delhi said, “With the current COVID-19 situation and the prevailing border tension between the two countries, it is going to be very tough for the Indian students who are pursuing medical education in China and wishing to come back to do practice.”

The current sentiment is posing a challenge for China-returned medical practitioners to position themselves even when they have the same credentials as any doctor in India.

“I assume and hope that this does not last longer,” he added.

India as a country requires trained medical practitioners to provide medical access to people in the remotest locations across the country and that is where China and other countries are giving opportunities to the aspirants to complete their medical education.

“We as a country can’t afford to ignore doctors who get trained on different specialties from countries like China, Bangladesh, countries from erstwhile USSR,” said Rajiv.

Workplace Discrimination

Another issue that China returned medical students are facing is a discriminatory behavior in hospitals. There are some incidents of verbal or professional discrimination at workplace for many doctors working even in COVID wards. Adding to their woes, the government hospitals in India don’t even consider these students eligible as they are only employed by the private sector hospitals in the country.

Akhilesh Vangari, a Hyderabad resident who was pursuing final year MBBS from Nanjing Medical University (NMU), China, came back to India in January 2020. Vangari is still waiting to go to China and complete his MBBS degree course.

“In India, if Aayush and BHMS doctors are able to serve the country with the similar pay scale as MBBS doctors, why are the MBBS students from Chinese medical universities not allowed to work in hospitals? Certainly, in a pandemic situation, the government could have utilised and given us some work, ” he said.

FMGE Issue

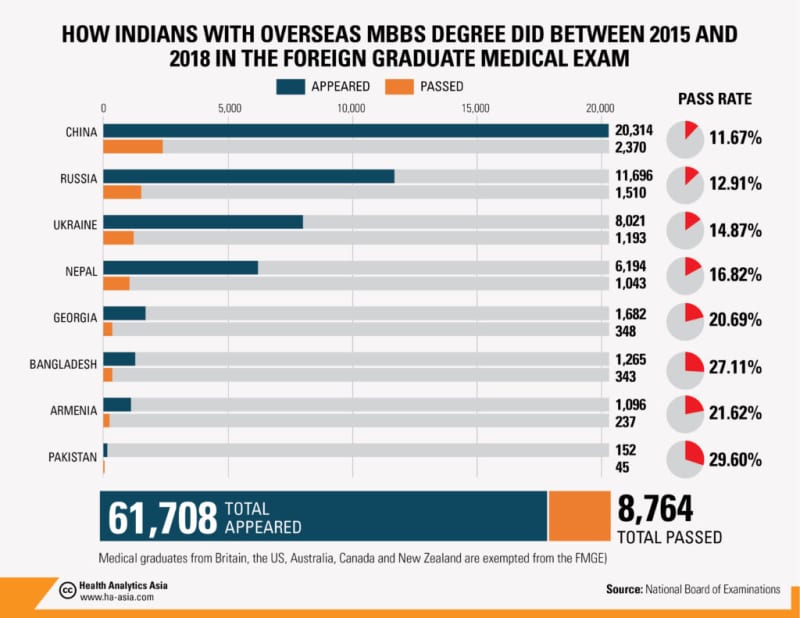

Indian students who go abroad for a medical degree have to clear a mandatory test called Foreign Medical Graduate Entrance (FMGE) conducted by the National Board of Examination on their return for doing practice in the country. However, a huge majority of candidates from medical colleges in foreign countries are not able to clear the test. The experience of Indian medical students returning from China has been extremely bad with reference to FMGE test as latest official data shows that out of 20,314 Indian MBBS graduates who passed out from Chinese medical institutions between 2015 and 2018, only 2,370 students could manage to clear the FMGE screening test (11.69% passed).

“Earlier the question paper would carry only a few clinical questions in the FMGE test, but this year, the test was completely clinical and was one of the toughest exams in the history of FMGE as it was way too advanced,” claimed Akhilesh.

Many of these students have experience of handling COVID wards in Chinese hospitals and are willing to serve in COVID hospitals in India as well. But they do not hold a practice license in the country, which makes them ineligible. “We have been requesting the concerned authorities to provide relief to at least India-born foreign graduate FMGE aspirants and reduce the qualifying percentage marks. We feel discriminated against in our own country,” said Akhilesh.

FMGE is not required for all countries. Students who completed degrees in the US, UK, Australia, New Zealand and Canada, do not need to take the exam.

Member of Indian parliament Anbumani Ramadoss recently wrote to India’s Health Minister Harsh Vardhan and said that the FMGE exam is being ‘deliberately made difficult and nearly impossible to pass’.

“The reason for this high failure rates [in the FMGE test] are the very difficult question papers,” Ramadoss wrote to the health minister.

“These graduates who have studied in foreign medical colleges that have good infrastructure are not able to get 50% marks [150 marks out of 300 marks] because the question paper is set in such high standard, much above the ones set for local graduates in their qualifying examinations.”

How Indians with overseas MBBS degree did between 2015 and 2018 in the Foreign Graduate Medical Exam

Future at stake

According to the data the results that were declared early September were not too encouraging — of the 17,789 students who took the exam on August 31, only 1697 managed to pass.

Siddhartha Ganguly who hails from West Bengal is pursuing final year of his medicine degree from Zhengzhou University, China. He was among a few lucky ones who could qualify the FMGE test. According to Ganguly, “Present scenario is very scary for most of the Indian medical students studying in China as well as in other foreign universities. Main problem that these students are facing is from the Medical Council of India and National Board of Examination who are purposely discriminating against students it seems.”

According to him, “Final year medical students in foreign universities are the ones facing most flack from these institutions. The middle year students, however, are not much affected as they are having their classes online.”

These students are expecting some respite and hoping the Indian government to take some concrete measures assuring their career and employment prospects in their own country.

Most of them are of the view that if at all there is some communication about the study environment in China between the two governments, it should be brought in open domain. Also, if there is a possible equation change which could trigger some safety issues for Indian students studying in China, that too should be clarified not only by the Chinese counterparts but also from the Indian government’s side.

Meanwhile, clear cut policies and guidelines must be put in place about Chinese medicine degree validity and employability in the native land.