If you’re struggling to understand the world right now, this is the one thing you must read.

Q4 2020 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

For many of us, the world we live in seems to have gone a bit crazy. Politics has become more partisan and rhetoric more extreme, even inciting violence. Inequality is at record levels.

Many Value Investing Heroes Struggle

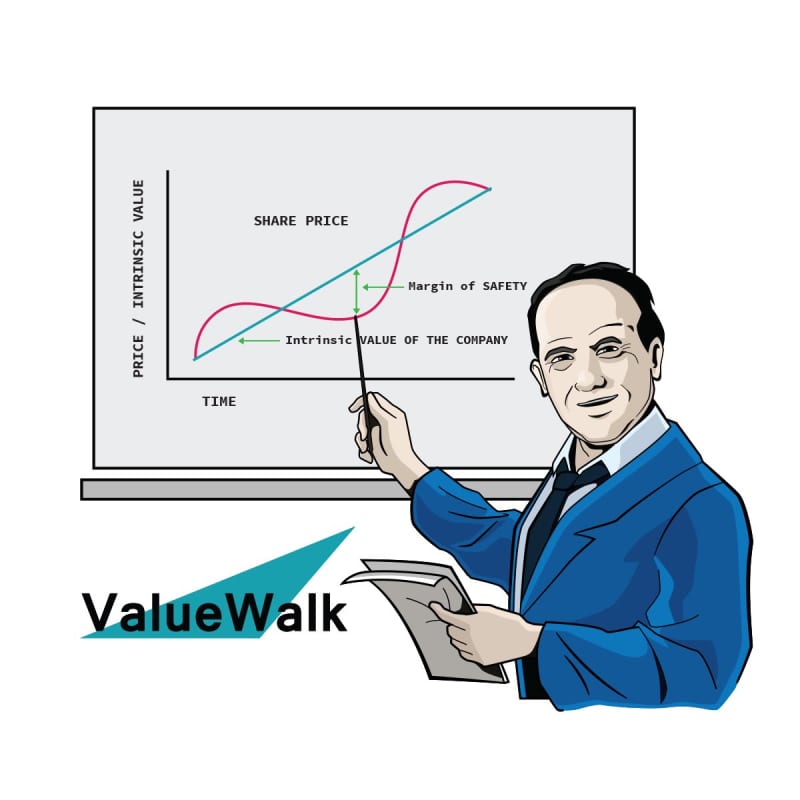

Markets too seem to make little sense. Many value investing heroes have struggled for over a decade, in spite of persevering with sensible and proven approaches. Seth Klarman was the latest this week to express his frustration with market behaviour, saying “The market’s usual role in price discovery has effectively been suspended.”

Meanwhile day traders and speculators make fortunes with little thought as to intrinsic value or even quality of management. Tesla is the poster boy for this new age. Accounting red flags, poor governance, a misbehaving CEO, missed targets and an inexplicable valuation have done nothing to dampen the speculative rush.

All this has left many of us totally exasperated. How does this make any sense at all?!

In order to understand, I think we must first ask, why has the world gone down this route?

While ‘unprecedented’ seems to be adjective of the moment, there is a precedent. And the precedent can be found in the introduction to Nate Silver’s book, The Signal and the Noise.

Silver recounts how, in 1440, Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press. This was a hugely important moment for civilisation, yet hardly anyone knows of the trouble it caused.

In the century that followed, a third of Europeans were wiped out directly and indirectly as a result of war and violence. Torture was commonplace. What caused this upsurge was that books became widely available, with the average cost falling from over $20,000 to $60 in today’s money; all thanks to printing. Many of these new books were religious texts - full of new, divisive and dangerous ideas.

Up to then, people had been used to living in villages. Communication was by word of mouth and with other locals. All of a sudden books came, proliferating new ideas and information. The public simply could not handle the change. The quality of decision-making collapsed.

Information Revolution

The parallels with today’s information revolution could not be clearer. With the rise of the internet, digital technology and big data, how we receive, process and relay information has changed completely; and we simply have not kept up with the pace.

Take politics; in the past politicians would have settled things over brandy and cigars in a country house. Now they must act in real time, tweeting and counter-tweeting, escalating and war-gaming. Neither our brains nor our institutions are designed to work like this. The Fed too has become game within a game where billions are wagered on why the Chairman said ‘maybe’ instead of ‘possibly’.

Whether it’s QAnon or BLM, 2020 has also seen movements and beliefs rise from nothing or be brought down by a single tweet. We’ve all witnessed how a misinterpreted email or text can escalate. Part of this is down to the simple fact that we are using new forms of media. Just like in the 15 century, people did not know how to handle the new medium, believing everything they read in a book must be true. It is no different to today’s phenomena of fake news, conspiracy theories and exaggerated headlines. Then, as people are funnelled into more and more confirming narratives, even the sanest among us can slip into manias.

Then there is the news itself. If you have a moment, do enjoy this wonderful 5 minute film by Adam Westbrook, asking, “How do we read online?”

The answer is we don’t. Instead, we flick through link after link, catching headlines. Our understanding is no longer through a carefully read article, but through dozens of repeated and hyperbolic headlines, all designed to grab our attention and capture clicks. Online providers are in a 24/7 battle for our attention, so everything has to be over-dramatised. A modest earnings miss and 2% share price fall, becomes 'Stock implodes as earnings collapse.’ A mild upgrade is translated into becomes ‘Stock surges as company smashes earnings.’ Hysterical reporting like this leads to feedback loops, pushing investors into a state of euphoria or panic.

Explosion In Hyper-Anxiety

In addition, there is the well documented explosion in hyper-anxiety. My wife is a GP, and today, nearly half her patients come to her with anxiety-related problems, such as insomnia. When she started training, it was less than 10%. The barrage of news and social media combined with constant real-time measurement and oversight is making us all perpetually distracted and anxious.

In research spanning over a decade, two leading psychologists[i] showed that the most effective ways to kill creativity and enjoyment of learning among children are to: 1) have children work for an expected reward, 2) focus them on an expected evaluation, 3) deploy plenty of surveillance, 4) set up restricted choices, and 5) create competitive situations.

In schools and workplaces, technology has exacerbated every single one of these. In this state, how can we possibly work with a level-headed and creative mindset?

Last but not least is the sheer quantity of data we now have at our fingertips. And yet, a number of famous studies[ii] have found that the more information you give experts, the worse their predictions become. Snowed under, we fall back on behavioural shortcuts and biases.

Our brains have never had to process information in this way and at this pace. This explains many of the explosive developments moving today’s markets, and recalling the upheavals of Gutenberg’s legacy. Is it any wonder we have, collectively, all gone a bit nuts?

How the Super-Investors did it.

In one of the most famous articles on Value Investing, The SuperInvestors of Graham & Doddsville, Warren Buffett recounted how a number of investors of the 50s, 60s and 70s delivered long run returns of well over 20%. These men generally worked alone. They would build their portfolios and hold them patiently (in the 1950’s the average stock holding period was seven years!). They would send off for annual reports and read them from cover to cover. They might spend an hour in the morning reading news of their companies in a financial newspaper, and maybe even meet management over lunch once or twice a year, or drive out to a factory or headquarters for the day. At the end of each year, they would write a short letter to clients explaining any portfolio changes and mentioning performance. Investing in the Graham mould was an exercise in patient and focused diligence.

By contrast, today’s professional investor will hold stocks for a few months on average. Their portfolio is monitored daily - not just in terms of performance, but myriad other metrics such as volatility, ESG or factor risks; all of which require constant adjustments. Hundreds of emails have to be dealt with, along with regulatory compliance and record keeping. Headlines and price moves ping constantly across his or her screens. I have seen first-hand that most professional investors today operate in a state of perpetual hyper-anxiety, focused entirely on surviving the present. They have neither the time nor the energy for reading or thinking. It is easy to see why market dispersions have gone crazy. Knowledge and sophistication have not brought understanding, let alone better results.

The way of the Future

The information revolution of the past two decades has completely changed how we receive, present, process and react to information. However, our brains have not changed.

I believe the next decade will not be about more information, more quickly. Instead, the next chapter will see people, governments and businesses experimenting with new ways to manage modern information flows in order to rediscover the art of good judgement.

To do so, we will have to reinvent everything, at both the personal and societal level. For example:

- The architecture and layout of buildings, such as offices and parliaments.

- Routines and lifestyles. Investors like Ray Dalio are already incorporating exercise, meditation, walking and reading time into their work routines.

- How we measure and monitor. Excessive measurement and oversight can lead to fear, over-reaction and a loss of creativity. Is spying on employees really a good thing? And are we even measuring the right things? For example, Instead of focusing on investment performance, financial consultant Stamford Associates selects investors based on behavioural profiling.[iii]

- How we lead people, and motivate them.

- How we sift information and even block it. A growing number of individuals and even businesses are turning off their social media accounts. Some bold CEOs and entire companies are abolishing emails.[iv] In his book, The Education of a Value Investor, Guy Spier outlines approaches, including working in a separate room to his Bloomberg terminal, not trading when markets are open and placing special emphasis on the order in which we assimilate information.

- How we communicate effectively. As many are rediscovering during lockdown, a stroll in the park or a handwritten letter may be more effective than an email or tweet.

The very essence of value investing is thoughtful and long-term decision making. That makes value investors the perfect pioneers for the new information age. If we want to avoid the fate of 15 century Europe, we will all need to think radically, experiment and adapt.

About the Author

Andrew Hunt is a global deep value investor and author of “Better Value Investing: A Simple Guide to Improving your Results as a Value Investor.”

[i] How to Kill Creativity, the Microsoft Way | Inc.com

[ii] Behavioral problems of adhering to a decision policy | Semantic Scholar

simple.models.68.pdf (ori.org)

[iii] Independent Investment Consultancy - Stamford Associates

[iv] Some Companies Are Banning Email and Getting More Done (hbr.org)

The post The Essence Of Value Investing And Why Many Struggle appeared first on ValueWalk.