Washington (AFP) - In 1994, as 800,000 mostly Tutsi people were beaten, hacked to death or shot dead in a 100-day bloodbath in Rwanda, the United States hesitated to call it genocide, eventually using the watered-down phrase "acts of genocide."

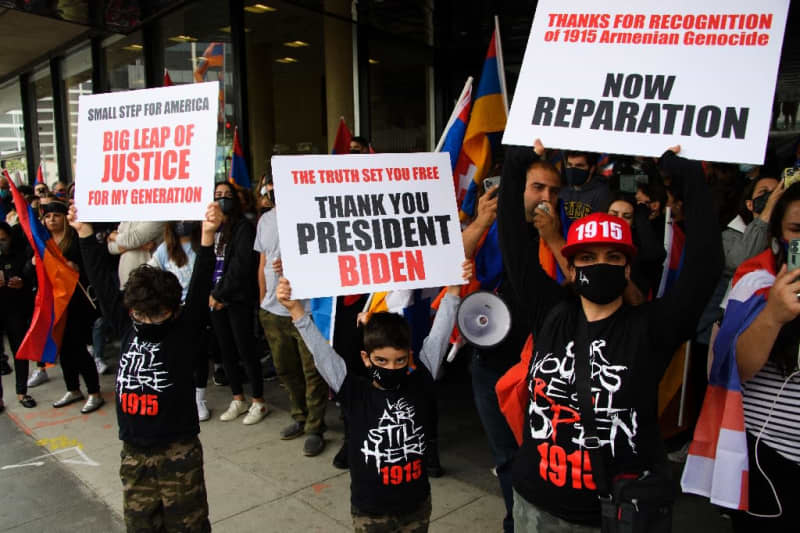

This year, in a matter of months, the United States has unreservedly made two such declarations -- first accusing China of genocide against the Uyghurs and other mostly Muslim Turkic people, and last week, defying years of pressure from Turkey, recognizing the Ottoman Empire's 1915-17 killings of Armenians as genocide.

The moves have heartened many rights advocates but experts doubt the US government is entering a new era of consistency over what is often seen as humanity's greatest evil -- or that statements will translate into action.

"These are steps forward in calling out atrocities for what they are," said James Waller, director of academic programs at the Auschwitz Institute for the Prevention of Genocide and Mass Atrocities.

"I don't know, though, that they signal a shift toward more universally wanting to make statements about events that may be interpreted as genocidal," said Waller, also a professor at Keene State College.

"I still think it's going to be a case-by-case basis that is going to be informed by political decisions."

Former secretary of state Mike Pompeo made the genocide determination on China's Xinjiang region on his final full day in office, capping off a tenure in which he boasted of ramping up pressure on Beijing.

President Joe Biden's declaration on the genocide fulfills a longstanding promise to Armenian-Americans, which went unfulfilled by Barack Obama when Biden was his vice president, and came at a time that relations with NATO ally Turkey were already fraught.

Alternative terms

The United States has not used the genocide term over the Rohingya, a mostly Muslim people in Myanmar of whom some 750,000 have fled to Bangladesh with accounts of razed villages, widespread killings and mass rape.

Waller tied the reluctance to expectations the United States could work with Myanmar's nascent democratic government -- which was overthrown by the military in February.

The United States has instead spoken of "ethnic cleansing" in Myanmar, and more recently in Ethiopia's Tigray region.

Ernesto Verdeja, an expert on genocide at the University of Notre Dame, said that general conceptions of genocide remained firmly tied to the specifics of the Holocaust, even though the legal definition is more universal.

"There's still a tendency to just see genocide as a really well laid-out plan of intentional destruction -- you don't have camps but you have something that looks like it," Verdeja said.

When violence does not fit the paradigm, many "simply brush it off -- it's not genocide, it's something else."

"In Rwanda, they talked about 'tribal hatred.' In Bosnia, they talked about 'ethnic ancient hatreds,'" he said.

There is an idea that "this is what those people do. It has a lot of racist undertones to it, and colonial assumptions baked into it."

'Never again'?

Another legacy of the Holocaust and the Genocide Convention signed in 1948 -- that the world will "never again" let it happen.

"If you recognize it, presumably you have an obligation to do something about it," Verdeja said.

US officials so far see limited leverage on Xinjiang, imposing sanctions but downplaying calls to boycott the Winter Olympics in Beijing.

Clinton did not want to be forced to intervene in Rwanda, with the United States haunted by images of US servicemen dragged through the streets a year earlier in Somalia.

But more recently, pressure campaigns have succeeded in bringing declarations on genocide.

Former president George W. Bush described Sudan's scorched-earth campaign in Darfur as genocide and Obama said the Islamic State extremist group was carrying out genocide against Christians, Yazidis and Shiite Muslims.

The Xinjiang declaration came after a push by US lawmakers across party lines who pointed in part to reports Beijing was limiting births among the minority -- one part of the Genocide Convention's definition.

Some critics say the Xinjiang declaration shows politicization as there is no evidence of mass killings.

"While the Chinese have severely repressed the Uyghurs, the scale of atrocities just doesn't begin to approach what the term genocide means in historical and conceptual and common-sense terms," said Michael O'Hanlon, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, who by contrast said there was a clear case to recognize the Armenian genocide.

"Moreover, the US-China relationship doesn't need gasoline thrown on it today. We should be resolute and firm but not incendiary."

Waller, who like Verdeja sees genocide in Xinjiang, said the key issue was not defining genocide but preventing it.

He voiced hope that Biden would strengthen an Atrocity Prevention Board set up under Obama to identify emerging crises.

"I do think that the US government is now coming back to the recognition of the role we can play in helping build strong societies that would be resistant to genocide, rather than simply responding to the fire once it's started."