Below is the writer's experience with changing visas. Your own experience may be different.Since I moved to Japan, I’ve heard people talk about “self-sponsored” visas more and more each year. The interest is understandable. Especially during trying times such as the coronavirus pandemic when job security isn’t always guaranteed.

Japan is also known to have a poor work-life balance. Salaries for full-time and easy-to-acquire jobs for foreigners, such as those teaching English, are relatively standard regardless of location but low in Tokyo compared to living in the countryside. Thus, working for oneself seems to be the best option for those who want free time and the opportunity to earn a decent standard of living.

After two years of being an assistant language teacher (ALT) with the JET Programme, I moved to the greater Tokyo area to pursue modeling while teaching art and design part-time with different companies. Wanting as much time as possible for my ever-changing schedule and with my visa renewal approaching, I decided to give “self-sponsoring” a try.

You can jump to a section with the links below:

Is there a self-sponsored visa?

The most important thing to know is that the “self-sponsored visa” is a misnomer. It is not a visa category and so it technically doesn’t exist.

The only visa categories available are those listed under the statuses of residence on the Immigration Services Agency of Japan’s official website. It would be more accurate to say “a valid work visa for a sole proprietor or part-time employee,” but that’s a mouthful and not great for SEO.

You still need a sponsor

You cannot self sponsor your visa. Your highest paying part-time employer or client is essentially still sponsoring you while you use the “Application for permission to engage in an activity other than those permitted by the status of residence previously granted” to list your income from work that falls under a different visa category. This will allow you to do freelance work such as modeling, writing, acting or other activities generally related to your current status of residence, but outside of your main job.

If you go this route, you need to have one of your part-time employers willing to fill out and attach their hanko (seal or stamp) to the paperwork. This employer will be considered your “main” employer and visa sponsor.

Thus, this creates an independent contractor relationship and your employer doesn’t have to treat you like a regular employee. It doesn’t cost them anything to sponsor you and they won’t be responsible for your insurance, taxes or pension. You have to take care of those by yourself and you are bound by law to do so.

Documents you’ll need

Since I came to Japan on the JET Programme, I was initially on a three-year Instructor visa. I switched to an Engineer/Specialist in Humanities/International Services visa and submitted an Application for Change of Status of Residence. All documents that you supply should be copies, as you won’t get the originals back.

Here is what I needed to apply for the Engineer/Specialist in Humanities/International Services visa:

- Application: You can fill out the first two pages yourself (the personal information) and even some company information on the last two pages. However, you’ll need to give those last two pages to your sponsor company to finish and stamp. You can find the application here.

- Passport

- Residence card-sized photo: You can take these at a photo booth. It needs to be attached to the application, but take extras just in case.

- Contracts from all current employers: This will provide proof of income, employment, etc.

- Gensen choshu hyo (源泉徴収票), or tax withholding slips: You can get this from your ward office or your employers.

- Your tax returns from the past two years: If you don’t have these, as was in my case, you will likely need to explain why in a letter included in your application package.

- Taishoku shomeisho (退職証明書), or proof of retirement: A document stating that you’ve left your previous job. Some companies may give this to you automatically, but not everyone does.

- Application for permission to engage in an activity other than those permitted by the status of residence previously granted: You don’t need this if you’re not working any jobs that fall outside your visa type. If you already have permission, you need to submit new applications when renewing or changing your visa. You can find the application here.

- Letter from your primary employer acknowledging other work: Again, you don’t need this unless you’re getting permission. If you are, you need to submit a letter from your primary employer (the one filling out the application) acknowledging this. It goes a lot smoother if you write the letter for them and have them print and sign/stamp it on their letterhead. It needs to include their business name, a short sentence of acknowledgment and the name of the business(es) you’re getting permission for.

- ¥4,000 handling fee: When permission is received, you need to buy revenue stamps at the post office and bring them with you to the immigration office. You can find the Certificate of Payment of Fee form here.

Proof of income

The above were the only documents I personally needed to apply for the Engineer/Specialist in Humanities/International Services visa. Some sources claim you must prove that you earn a certain amount of annual equal to ¥3,000,000 or ¥250,000 per month. I was not asked to do so, but that may be because my tax withholding slips and contracts already supplied that information.

Regardless, if you can provide documents for more earned income, it doesn’t hurt to do so and may improve your chances of being approved.

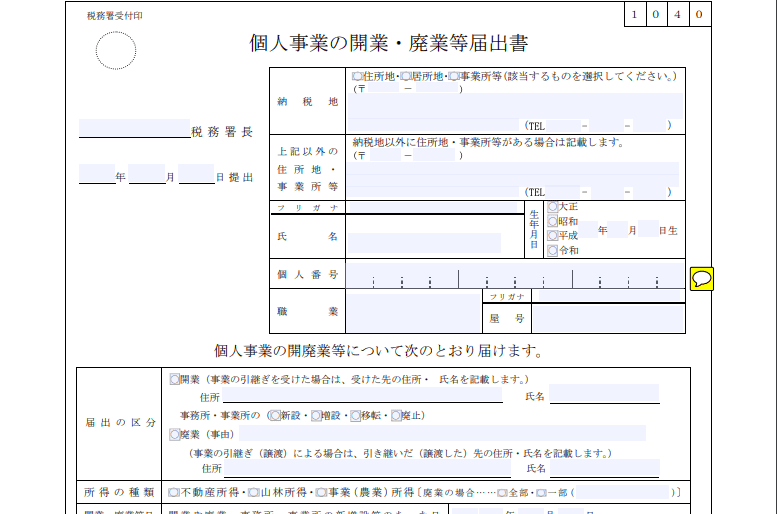

The sole proprietorship form

Some sources will recommend filing the kojin jigyou nushi (個人事業主), or Sole Proprietorship form (Japanese) with your local tax office. Essentially, you need this form if you are starting your own business. For example, a chunk of your income was coming from private students. In that case, you would also need to make contracts for all your students and provide proof of income.

However, I was an employee who has signed contracts with businesses, not a person acting as a business, so I did not apply for or need this form.

I did attempt to get the form from my city office but a clerk explained to me the purpose of the form and why it wasn’t necessary for me to file one. If you’re unsure, please visit your local tax counter, explain the work you do and let them help you make the decision.

Getting sponsored as a part-time employee

Getting one of my employers to be my sponsor was the most daunting part of the entire process. I worked for three companies at the time. Let’s call them companies A, B and C.

Although they wished me luck with the process, Company A lamented that they did not sponsor visas for part-timers for any reason. Company B—whom I had permission for—fell outside of the visa type I was trying to acquire, so I did not approach them at all.

Company C initially seemed eager to sponsor my visa, but upon realizing that filling out the paperwork would reveal some company financial information, they changed their mind. Eventually, one of their immigration specialists stepped in and got them to agree that if she accompanied me to immigration with the paperwork—and didn’t let me see it—they’d finish and sign it. With that, Company C became my sponsor.

Tax problems

The other difficulty was specific to me being from a tax treaty country. Since I arrived in 2017, the agreement that exempts U.S. citizens from paying Japanese income taxes their first two years was still applicable and therefore I had no record of paying income taxes in my application package.

Of course, the immigration officer wanted to know why this was and through translation by the specialist, we communicated the treaty to him. He nodded in understanding, handed me a sheet of lined paper along with an envelope with my case number, and asked me to please go home to write down what I just explained and mail it back to them.

Then, whoever would decide on my visa would need to read that explanation to understand why my tax information was missing.

I went home and typed up a short explanation in English, translated it into Japanese via Google Translate, printed it and handed it to immigration in person the very next day. I was taking no chances.

Getting approved

Two weeks later, I received a postcard telling me to return to the immigration office and bring revenue stamps for the payment of my application fees. I was excited because I knew this meant my visa renewal was approved.

After an anxious wait in line, I walked out with a new permission stamp in my passport and a shiny new three-year residence card. I honestly wasn’t expecting a three-year renewal—especially not as a part-time worker.

So that’s how I “self-sponsored” my visa. Hopefully, this article helps and reassures you if you’re thinking about doing it too.

Have you self-sponsored your work visa or plan to do so? Was your experience different from mine? Let us know in the comments!