Kerrisdale Capital is short shares of Virgin Galactic Holdings Inc (NYSE:SPCE).

[soros]

Q1 2021 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

Kerrisdale Is Short Virgin Galactic

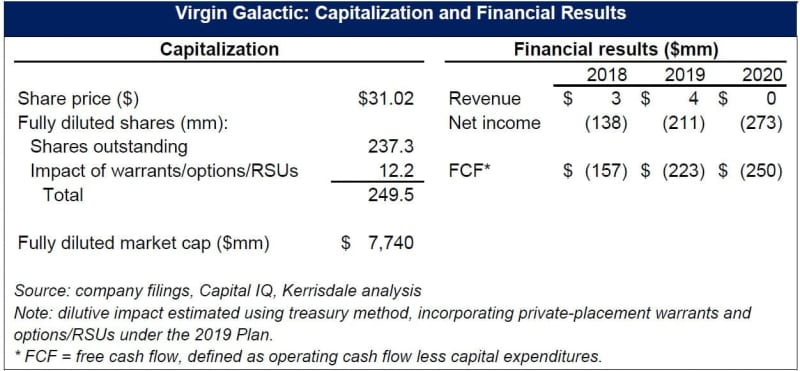

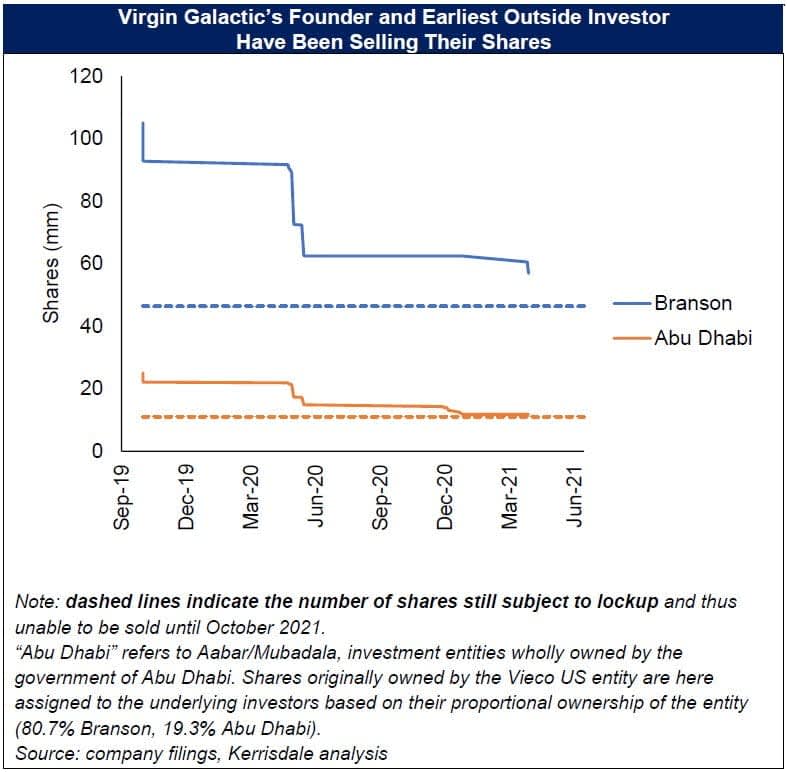

We are short shares of Virgin Galactic Holdings, Inc., often described as the only publicly traded space-tourism company. After going public in October 2019 by way of a merger with a “blank check” company, Virgin Galactic has seen its share price and trading volume soar. It’s become a retail darling, with day traders captivated by images of billionaires donning space suits, blasting off from launchpads, and looking down on the blue marble of Earth.

But Virgin Galactic’s $250,000+ commercial “spaceflights” – if they ever actually happen, after some 17 years of delays and disasters – will offer only the palest imitations of these experiences. In lieu of pressurized space suits with helmets – unnecessary since so little time will be spent in the upper atmosphere – the company commissioned Under Armour to provide “high-tech pajamas.” In lieu of vertical takeoff, Virgin’s “spaceship” must cling to the underside of a specialized airplane for the first 45,000 feet up, because its rocket motor is too weak to push through the lower atmosphere on its own. In lieu of the blue-marble vista and life in zero-g, Virgin’s so-called astronauts will at best be able to catch a glimpse of the curvature of Earth and a few minutes of weightlessness before plunging back to ground.

This isn’t “tourism,” let alone Virgin’s more grandiose term, “exploration”; it’s closer to a souped-up roller coaster, like the “Drop of Doom” ride at Six Flags. It isn’t even really “space.” The traditional international definition of “space” (known as the Kármán line), which Virgin Galactic itself once targeted, puts the boundary at an altitude of 100 km, which the company’s technology can’t reach. Indeed, Jeff Bezos, whose Blue Origin is also working on suborbital flights, noted this Virgin weakness in a 2019 interview, adding that Blue Origin’s “mission” has always been “to fly above the Kármán line, because we didn’t want there to be any asterisks next to your name about whether you’re an astronaut or not.” Veteran astronaut Chris Hadfield put it even more bluntly back in 2013, calling Virgin Galactic’s planned offering “not much of a space flight…They’re just going to go up and fall back down again…[W]hether that’ll be enough for the quarter-million-dollar price tag? I don’t know.” With Blue Origin’s superior experiences likely to beat out Virgin’s in the near term, and SpaceX’s multi-day excursions – going into Earth’s orbit and staying there for several days rather than several minutes – winning out in the longer term, Virgin’s moment in the sun may be over soon after its first real flights finally lift off.

Hadfield also presciently warned, “Eventually they’ll crash one” – and was proven right just twelve months later by a fatal catastrophe. Tests of Virgin’s systems have already killed four people, and since the company is “not building new technologies but just copying very old ones,” as one industry veteran complained, the company’s crude aerospace technology will likely lead to more deaths. How quickly will spaceflights screech to a halt as fatalities pile up? Dangerous and unappealing, Virgin Galactic’s sole product – whose official commercial launch has been delayed so many times it’s a running joke – cannot justify the company’s $8 billion valuation. “Virgin” or not, this business is screwed.

Company Background

Despite never having flown a single paying customer, Virgin Galactic has a history that stretches back decades. It was born out of the X Prize, an effort initiated in 1996 by the entrepreneur Peter Diamandis to stimulate the development of private-sector spaceflight by offering $10 million to the first non-governmental organization to launch a manned vehicle into space. “Space,” for the purposes of the prize, began at 100 km (about 62 mi) above the earth’s surface – a boundary known as the Kármán line (named after Theodore von Kármán, a Hungarian-American scientist). Burt Rutan, a maverick aerospace engineer, came up with an unusual design that was optimized to win the prize at minimal cost: a specialized plane would carry a craft called SpaceShipOne up into the air and drop it; SpaceShipOne would then ignite its rocket motor, shoot almost vertically up toward the Kármán line – and very soon plummet right back down to earth. A complex mechanism on SpaceShipOne’s tail, referred to as the “feather” and reminiscent of a badminton shuttlecock, would slow the descent.

This design lacked anything close to the power to get into or out of orbit, but, after years of struggle to make it work, it was just barely good enough to, in the words of one reporter, “briefly slap the rim of space”; thus SpaceShipOne won the X Prize in 2004. It was around then that Sir Richard Branson, the flamboyant British business mogul best known for his Virgin Atlantic airline, entered the story. Branson’s vision was to license and scale up Rutan’s SpaceShipOne technology and use it as the basis for the world’s first “spaceline,” “offering commercial flights to space by 2007-8” for a few hundred thousand dollars per passenger.

But 2007 came and went, marked by an on-the-ground nitrous-oxide explosion that killed three people working on Virgin’s craft – but no commercial flights. Years passed, with new technical difficulties always cropping up to impede the company’s progress, including another fatal accident in 2014 that destroyed the first iteration of SpaceShipTwo. Branson’s endlessly repeated false predictions that commercial service was just around the corner became notorious; in his own words, speaking to a journalist in 2018, “It would be embarrassing if someone went back over the last thirteen years and wrote down all my quotes about when I thought we would be in space.”

All of those years of failure didn’t come cheap – from 2017 to 2020 alone, the company burnt more than $700 million of cash – so Branson periodically sought to shore up Virgin Galactic (and his other, less sexy space-related effort, the satellite-launch business Virgin Orbit) with infusions of outside money. In 2009 Abu Dhabi invested $280 million for a minority stake in these businesses, and in late 2017 Branson signed a memorandum of understanding for $1 billion from Saudi Arabia – but the deal fell apart the following year in the wake of the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi. Help arrived from an unexpected quarter: a SPAC called Social Capital Hedosophia, created by two tech investors with no experience in aerospace. Within three months of hearing from a financial advisor about Virgin Galactic’s funding needs, Social Capital Hedosophia had already sent the company a letter of intent to invest in it and take it public. In October 2019, the process was complete, and Virgin Galactic, now trading on the New York Stock Exchange, projected “a June 2020 commencement of commercial operations,” with Branson himself as the long-awaited first passenger.

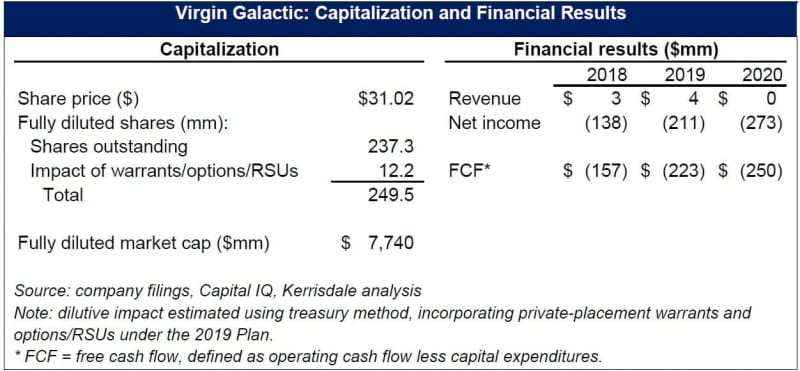

Of course, June 2020 came and went; commercial operations did not commence. At the time of its deal with Social Capital Hedosophia, Virgin Galactic projected that its EBITDA would reach $146 million in 2022; today, however, the consensus EBITDA estimate for 2022 (via Capital IQ) is negative $129 million – a staggering $274 million shy of the original target. But, carrying on in Branson’s tradition of delusionally optimistic messaging, the company insists it’s still on track.

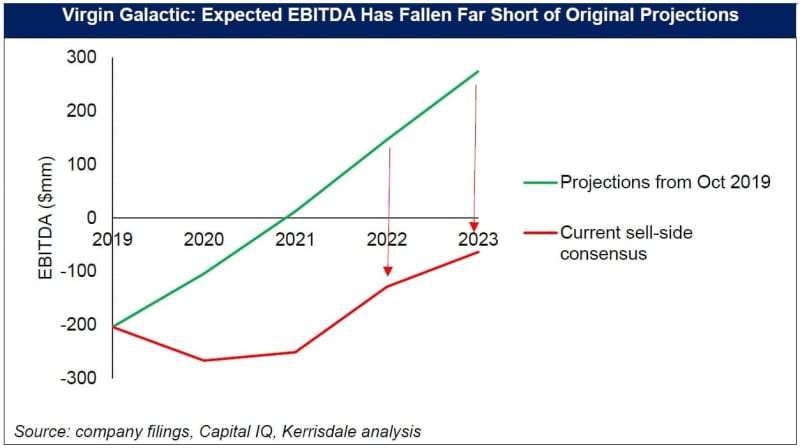

Interestingly, Social Capital Hedosophia initially sought to merge with both Virgin Galactic and Virgin Orbit, but, according to the subsequent proxy statement, “Mr. Branson conveyed a preference on behalf of Virgin management for a potential business combination transaction involving…the ‘Virgin Galactic’ business only” – retaining the more practical, less speculative Orbit business but relinquishing control over the 15-year-old suborbital “space tourism” boondoggle. In fact, as part of the initial SPAC transaction, Branson and Abu Dhabi didn’t just issue new shares in Virgin Galactic; they sold 12% of their preexisting stake at just $10 per share. Though they’re prohibited until October from selling more than half of their remaining shares, these original investors have made good progress in liquidating what they can, selling shares in the open market last May and June (with respect to both Branson and Abu Dhabi) and continuing to sell in December and January (with respect to Abu Dhabi) and April (with respect to Branson). All in, relative to their pre-SPAC position, Branson and Abu Dhabi have reduced their combined holdings by 47% at a weighted-average sale price of $15.16 per share – 51% below the current price.

Branson and Abu Dhabi are not alone in selling Virgin Galactic shares at prices much lower than the current trading level. Chamath Palihapitiya, the co-founder of the Social Capital Hedosophia SPAC and chairman of Virgin Galactic, has economic exposure to Virgin Galactic shares and warrants via the SPAC sponsor entity over which he shares control with his business partner Ian Osborne. In addition, as part of the SPAC transaction, Palihapitiya purchased 10 million shares directly from the original owners (Branson and Abu Dhabi) at a price of $10 per share. On December 14th and 15th, Palihapitiya sold 3.8 million of these shares – “to help manage my liquidity,” he tweeted – at a weighted-average price of $25.74, 18% below the current level.

Even Virgin Galactic itself has hit the bid, raising money in August 2020 by selling shares at an effective price, net of offering costs, of $18.60 per share – 40% below the current level. Thus all the parties most intimately familiar with Virgin Galactic – its founder, its earliest external investor, its chairman, and the company itself – have been willing sellers even at what now look like “low” prices, taking advantage of the enthusiasm of less informed outsiders.

Read the full report here.

The post Virgin Galactic: Putting the Zero in Zero-G – Kerrisdale appeared first on ValueWalk.