Washington (AFP) - Twenty-five years ago, French biophysicist Pascal Mayer had an idea that seemed nothing short of "crazy." Today, his research has paved the way for a rapid and inexpensive DNA sequencing technique used around the world in the battle against Covid-19.

On Thursday, Mayer, 58, who hails from the town of Riom in central France, was awarded the prestigious Breakthrough Prize in life sciences, alongside British researchers Shankar Balasubramanian and David Klenerman.

The American prize, launched by Silicon Valley entrepreneurs to recognize the latest scientific advances, carries an award of a hefty $3 million, compared to $1 million given to Nobel Prize laureates. Mayer and his colleagues will get $1 million each.

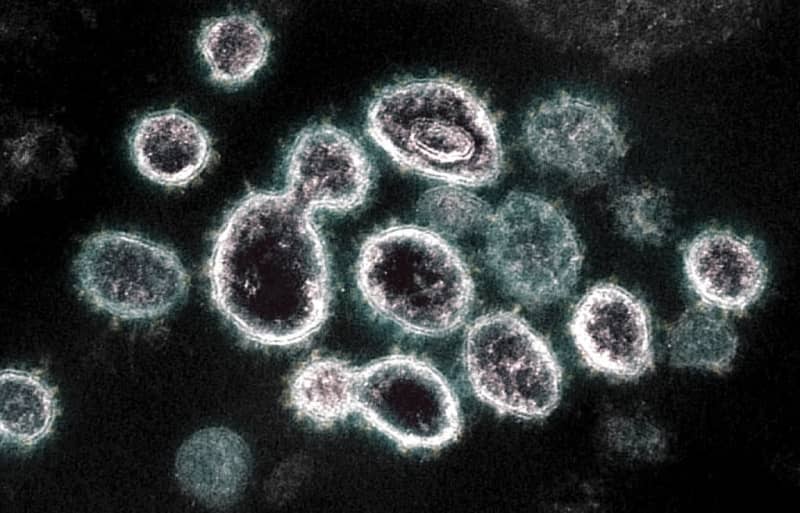

Thanks to the new method, known as next generation sequencing (NGS), scientists can analyze coronavirus mutations day by day to identify and monitor new variants.

Without this technique, studying the rapidly spreading new Covid-19 mutations would be much more costly and, more importantly, take much longer, Mayer told AFP.

But back in 1996, when Mayer began developing the idea, it sounded wild.

"It seemed crazy, so I looked pretty crazy when I talked about it," said Mayer, who now works at his own bioresearch company.

DNA colonies

A genome is a complete set of an organism's genes: its hereditary information.

Each gene represents a small piece of DNA, which in turn, consists of four letters: A (for adenine), T (thymine), C (cytosine) and G (guanine).

Made up of 23 chromosomes, the human genome contains more than three billion letters.

"It's a bit like having an encyclopedia consisting of 23 volumes," Mayer explained.

To sequence the genome is to "read" the order of these letters.

The sequencing of the first complete human genome was completed in 2003, after ten years and an investment of over $1 billion. The technique that was used then is called Sanger sequencing.

Thanks to NGS, also called massive parallel sequencing, the process can now be done overnight at a cost of $1,000.

How is that achieved? Instead of reading the pages of each book one by one, they are all read simultaneously.

"It's like putting all the pages on a soccer field, and being able to take a photo of the field at once," explained Mayer.

One of the keys to his technique is creating clusters of DNA, by cutting up the genome into small pieces, then creating thousands of copies of them and grouping them into islands of sorts.

Assembled together, they can be read simultaneously and more easily by fluorescence.

Mayer said the simplicity of the technique is its key strength and a source of pride for him.

The sequencing takes place "with a stroke of the pipette," he said.

17,000 machines

After studying at the University of Strasbourg and completing postdoctoral fellowships in Canada and in France, Mayer tested his idea for the first time in Geneva, in the research center of a pharmaceutical company where he then worked.

Two key patents were filed in April 1997.

The technology was later acquired by a start-up founded by Balasubramanian and Klenerman, two British scientists working on the same problem.

Their company was eventually bought by the US genetic research company Illumina, the global leader in genetic sequencing, which has 17,000 sequencing machines around the globe.

Besides Covid-19 research, massive parallel sequencing is widely used to diagnose and treat certain cancers and rare diseases.

It is also used in forensic investigations to analyze DNA samples from crime scenes.

Mayer does not own the property rights to the sequencing method, so he doesn't share in the profits.

But he hopes the award will give a boost to his bioresearch company Alphanosos, which he founded in 2014.

Mayer intends to invest a part of his award to fund projects at his company, including treatment for coronavirus.